This is the first of a series of posts detailing the paternal ancestry of my maternal grandfather Frederick England from the late 18th Century to the early 20th. This part will focus on the period from 1797 to around the 1850s.

* * *

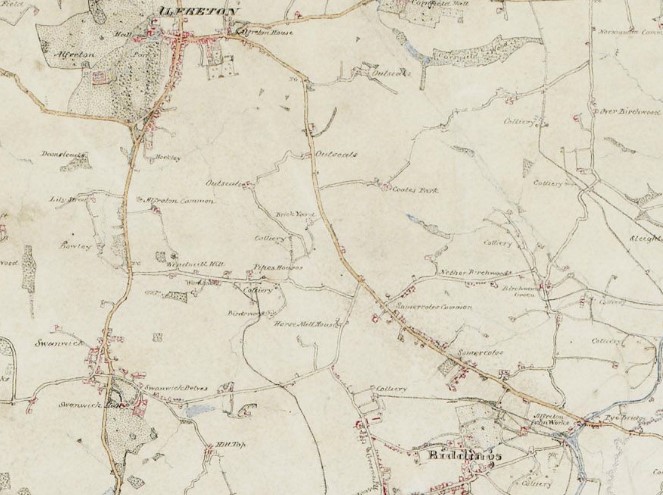

The England family name seems to have originated independently in a number of different places where Anglo-Saxon ‘Englishmen’ were historically a minority, including the borders of England and Scotland and the Scandinavian-dominated Danelaw in Yorkshire and the East Midlands. Given where his immediate family came from it seems likely that the earliest ancestors of Frederick England would have come from the second of these two areas, and indeed the earliest documentary evidence I have found featuring the name of one of his England ancestors appears in the parish registers of St. Martin’s Church in Alfreton, Derbyshire. There on 20 March 1797 the marriage of Samuel England (b. c. 1772 – bur. 28 January 1829) to Hannah Stendall (b. c. 1779 – bur. 15 June 1809, Alfreton, Derbyshire) took place, witnessed by Joseph and Elizabeth England. Given their surnames it seems likely these witnesses were members of Samuel’s family but their exact relationship is unknown. Between them Samuel and Hannah had four children, the last of whom, Frederick’s great-grandfather James England was baptised on 15 June 1809, the same day Hannah was buried suggesting she may have died in childbirth.

The next time we encounter James is in the parish registers of St Mary’s Church in Greasley, Nottinghamshire for his wedding to Alice Sisson (bp. 3 April 1820, Strelley, Nottinghamshire – bur. 18 August 1896, Swanwick, Derbyshire) on 23 May 1836. The following year, James and Alice had moved back to James’s home parish, and according to the birthplace of their first daughter Hannah (perhaps named for his late mother?) were living in the small community of Pye Bridge on the Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border. This record also confirms that James was employed as a collier (coal miner) at the time, and aside from the 1841 census on which he is listed as an iron ore miner, James appears to have worked in the coal industry his entire life.

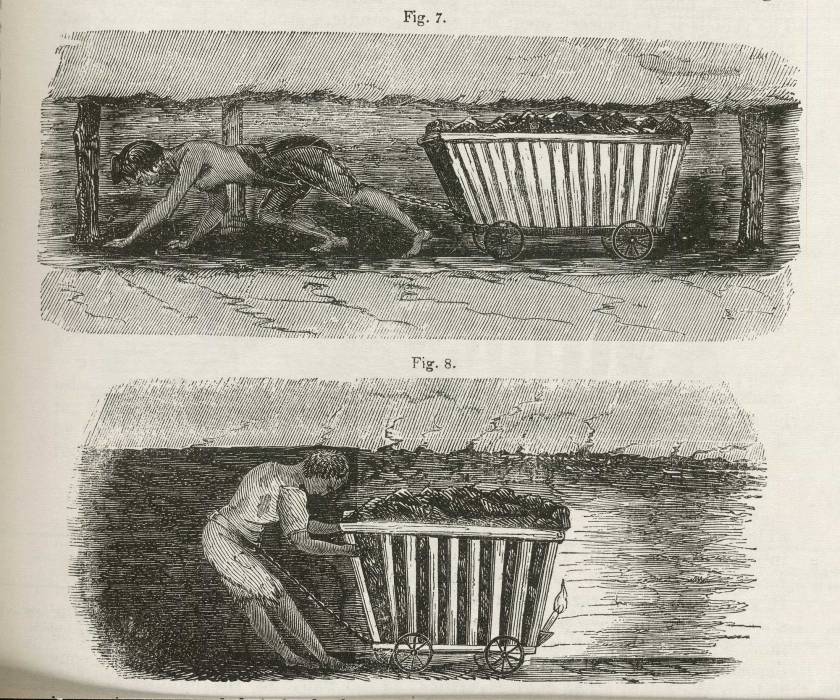

By the mid-nineteenth century, the East Midlands region which included Swanwick Colliery, James’s place of work, was one of the most heavily industrialised places in the world. At this time however mining was extremely dangerous work and poorly paid. Safety measures were almost non-existent and the living conditions of the workers were often cramped and overcrowded (by the time of the 1851 census James’s household included nine people). It was common for miners to start work before day break, spend all day underground and not emerge until after sunset. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that the area was an early hotbed of working class radicalism, with the Swanwick Miners’ Association organising an ill-fated strike as early as 1844, in which James England could well have participated.

On 20 October 1851 when James was only forty two he was killed in an accident at Swanwick colliery. According to a subsequent inquest he had been “using a crow bar for the purpose of removing a prop, when the bar slipped and springing back caught him such a severe blow in the pitt [sic] of the stomach that it caused immediate death” (The Derby Mercury, 5 November 1851). He was buried on the 23rd of that month, leaving behind his wife and five surviving children.

So what of the family James left behind? Between 1837 and 1850, he and Alice had had at least seven children, whose names were:

- Hannah (bp. 21 May 1837, Pye Bridge, Derbyshire – bur. 14 June 1842, Pye Bridge, Derbyshire)

- Ann (bp. 10 February 1839, Pye Bridge, Derbyshire – bur. 5 March 1879, Swanwick, Derbyshire)

- George (b. c. April 1842, Pye Bridge, Derbyshire – d. c. November 1918, Derbyshire)

- Samuel (b. 3 September 1844, Somercotes, Derbyshire – bur. 7 April 1845)

- James (b. 4 April 1846, Sleet Moor, Derbyshire – d. 15 May 1933, Nuttall Street, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- Mary (b. 6 May 1848 Sleet Moor, Derbyshire – d. c. August 1945, Derbyshire)

- Thomas (b. 26 May 1850, Sleet Moor, Derbyshire – d. 21 February 1918, Riddings, Derbyshire)

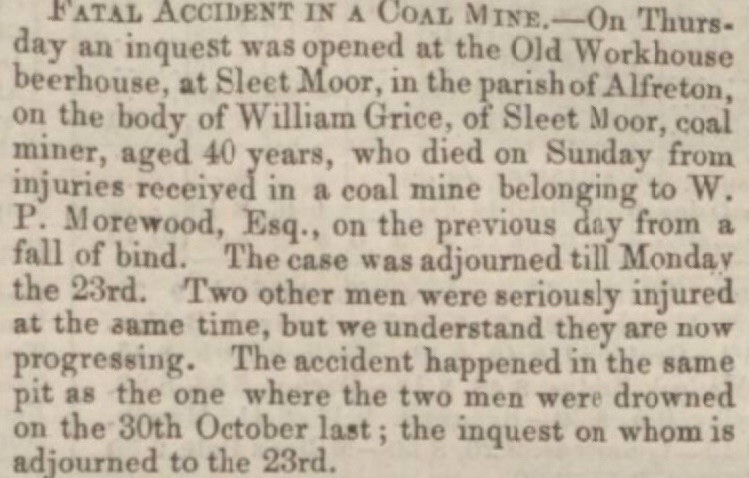

Just less than two years after James’s death, Alice remarried on 17 May 1853 to another coal miner, William Grice (b. c. 1823, Min, Leicestershire), with whom she had at least three more children:

- Alice (b. 1 April 1855, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. August 1925, Derbyshire)

- William (b. c. November 1856, Sleet Moor, Derbyshire)

- Elizabeth (b. c. 1860, Sleet Moor, Derbyshire – d. c. May 1910, Derbyshire)

We of course cannot say whether Alice remarried for love, the need to support her children economically or a combination of the two, but in the years between the death of James and her second marriage she must have struggled to provide for her children, especially as her mother Ann was no longer around to help having died nine years earlier (Alice was the eldest of two two ‘illegitimate’ sisters, no father is named on her baptism record but on the record of her marriage to William Grice thirty three years later she gives her father’s name as Thomas Dewes). Tragically, only ten years into their marriage Alice’s second husband William died, like her first, in an accident at Swanwick Colliery on 15 November 1863. According to a report in The Derbyshire Times, two other men were seriously injured, and the accident had occurred in the same pit where two men had drowned the previous October.

The regularity of pit fatalities like those of James and William at this time is quite shocking. A search of the Coal Mining History Resource Centre’s database of Coalming Accidents and Deaths shows that between 1851 and 1919 there were thirty five incidents reported at Swanwick Colliery alone. According to this database James has the dubious honour of being the first man to die at Swanwick Colliery, but unfortunately many of his descendants also appear among the lists of dead and injured.

After Alice’s marriage to William the family never left the Sleet Moor area, the small semi-rural community located just south of Swanwick Colliery but North East of Swanwick village. Growing up in the shadow of the Palmer-Morewoods’ great pit it’s hardly surprising that all her children who survived infancy grew up to either work down the mine or marry a collier. Her eldest son George suffered bruising and a broken collar bone in a pit accident at the age of forty three (The Derby Daily Telegraph, 24 June 1885, p. 2, col. 6.) but survived to live another twenty six years. Alice and James’s youngest son Thomas, Frederick England’s grandfather, also met with an accident aged just fourteen. His resulting spinal injuries were so severe he was prevented from ever working down the mines again, but in his case this turned out to be something of a blessing as it led to a career as a clerk above ground. Later, despite his humble origins he would go on to hold an important managerial position in a local chemical works at a time when such social mobility was unusual, and became a councillor for the Somercotes and Riddings Urban District Ward, perhaps providing the origin of the England family’s later involvement in local politics. His story however will be explored in the next post.

This is a vivid picture of a tough and unforgiving way of life. It would be fascinating to know more about Thomas and his rise from injured collier to clerk then manager. I wonder how likely it is that you’ll find out more?

LikeLike