Before moving on to my maternal grandmother Julia Mary Mills, there is one more family among her husband Frederick England’s ancestors whose story I’d like to tell. In previous posts I have looked at the direct male-line ancestors of both his father Thomas England and his mother Maud Ling, but so far have not considered either of his parents’ female lines. In this series I will be talking about the ancestors of Maud Ling’s mother Mary Ann.

* * *

Over the course of her life, Frederick England’s maternal grandmother went by a confusingly large number of names. Her death certificate from 1938 records her as ‘Mary Ann Bestwick’ (see First steps in family history (part 2)), the name she adopted following her second marriage in 1910, but prior to that she had been ‘Mary Ann Ling’ since marrying Maud Ling’s father John in 1871. Her maiden name according to her marriage certificate from that year was ‘Buxton’, but both her birth and baptism records confirm she had actually been christened ‘Mary Ann Hall’. How and why this name change came about will be explored later, but let us look first at the origins of the Hall family whose name she inherited.

Mary Ann’s earliest known ancestor on the Hall side was her grandfather, John Hall, who was born in about 1794 in Long Eaton in south east Derbyshire. At around twenty three years of age he married Ann Burton (bp. 3 January 1797, Lambley, Nottinghamshire) on 25 September 1817 in Ann’s home parish of Lambley, a remote, sleepy village in rural Nottinghamshire whose most notable geographical features include ‘The Dumbles’ and ‘The Pingle’. Ann’s parents, John Burton and Amy Charlesworth, had roots in both Lambley and the slightly larger market town of Arnold further west, and including Ann they appear to have had at least thirteen children.

John and Ann Hall’s whereabouts in the years immediately following their marriage are unclear. The 1841 census shows them living with three boys born between 1826 and 1836 who were almost certainly their sons, but as that year’s census did not state the relationships between members of the same household it’s impossible to say for sure. Their names were:

- John Hall (b. c. 1826, England)

- Thomas Hall (b. c. 1831, England)

- William Hall (b. c. 1836, England)

We have no way of knowing where the family were living when they were born as unfortunately the census only records that they were born outside their current county of residence (Derbyshire). This together with their suspiciously ’rounded-down’ ages (15, 10 and 5) has made locating their baptism records extremely difficult. To date the only child of John and Ann Hall’s whose baptism record I have found is that of their daughter, Miriam, who was christened in Lambley on 30 June 1833. The date and place suggest the Halls may have stayed in Ann’s home village after they were married until at least the early 1830s, but without further evidence it’s difficult to get an accurate timeline.

What is certain is that by 1841 the family had moved to Queen’s Head Yard in Alfreton, Derbyshire, and the reason for their move may have had something to do with John’s occupation as a cotton framework knitter. At this time hosiery was still an important part of Alfreton’s economy, and the town would have been an attractive destination for unemployed framework knitters seeking work. While less hazardous than coal mining, which gradually supplanted framework knitting as the area’s main industry later in the Nineteenth Century, the life of a ‘stockinger’ was far from easy, as Denise Amos writes:

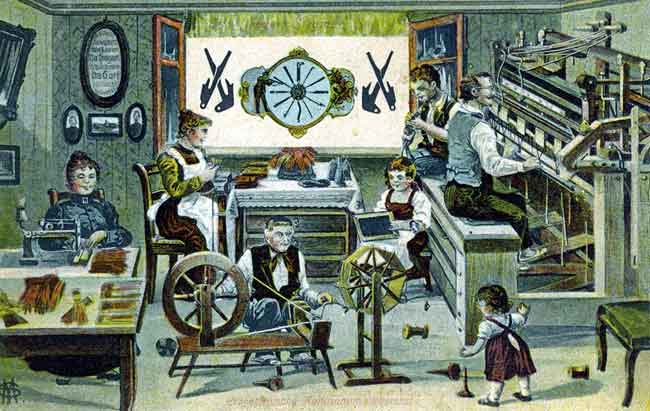

Framework knitting was a domestic industry. William Gibson, a manufacturer, gave evidence that many of his workers worked together and that it was an entirely domestic manufacture. The whole family worked in the industry. The men normally did the knitting, the women spun the yarn and finished the hose, which required needlework skills for seaming and embroidery. The work was given out through a middle person and the knitters had to accept the wage or go without work. For many they lived in abject poverty and wretchedness. The children would begin to help as soon as they were able. Ben Glover, a knitter said that the reason the children stayed in the industry was because their families were poverty-stricken; they were born to it, they remained in it and they died there! There was also the problem of unionisation which did not exist in the knitting industry. The knitters could not stop other redundant hands coming into the trade and therefore the price of labour was kept low.

Although only John and his oldest son John Jr. were recorded as framework knitters in the 1841 census, it is likely the whole family would have been involved in some capacity. Indeed by 1861 John’s wife Ann was also listed as a framework knitter at their new Derby Road address, even though as Amos notes above, this was traditionally a male occupation. This may have been because, for reasons unknown, her husband was absent on census night that year and she was simply filling in for him while he was away, but the fact that she was even capable of doing so suggests a more flexible division of labour than the one Amos suggests.

In addition to to their work as stockingers, John and Ann were by this time supplementing their modest income by renting out their children’s empty rooms to a series of lodgers. In 1861 these included two Leicestershire coal miners, Thomas Adkin and William Linsley, and in 1871, following their move to 15 Malthouse Row on King Street, two fellow stockingers named Thomas Beresford and Samuel Fletcher. Astonishingly, John was still listed as a framework knitter in 1871 despite the fact that he was by then seventy seven years old, but within four years both he an Ann would be dead. Ann was the first to go aged seventy six. She was buried in the grounds of St. Martin’s Church in Alfreton on 25 August 1873. John followed soon after in around May 1874 at the grand age of eighty one.

* * *

The fates of John and Ann’s three sons, John Jr., Thomas and William after 1841 are unknown, as that is the last census on which any of them can be found. We know rather more about their daughter Miriam however, who was not living with her parents in 1841 and did not show up in Alfreton until the following decade. Miriam was Mary Ann Hall’s mother and Maud Ling’s maternal grandmother. In the next post I will be focusing on her story as well as that of her husband, the tailor, postman, greengrocer and publican of the Devonshire Arms, Charles Buxton.

These tales of hardship in the various branches of the textile industry are fascinating ones. We were at Quarry Bank Mills in Cheshire on Sunday, and the lives of the young apprentices there were so hard – yet so much better than the lives they endured in the workhouses from which they had come: I wrote a post about it yesterday.

LikeLike

I’ve just read your post, excellent as always, and thanks for your support!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are offering such helpful tips, as well as writing a fascinating history. What’s not to like?

LikeLike

Robert,

I’d like to let you know that your blog is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2016/05/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-may-27-2016.html

Have a wonderful weekend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great, thank you so much! Hope you have a great weekend too.

LikeLike