This is the concluding third part of my history of the Jones family of North Wales and Liverpool, the paternal ancestors of my grandfather Rowland Bevan Jones. For the first chapter in this series see Keeping up with the Joneses (part 1). Content warning: contains descriptions of violence and cruelty to children.

Of the ten surviving children born to John Ellis Jones and his wife Hannah (née Roberts), it is their eldest Hugh Lloyd Jones whose life is the best documented, but not necessarily for reasons he would have chosen. Born 30 January 1867 at Mertyn Farm in Flintshire, in his first year he had moved with his parents to Liverpool’s Bootle district, before travelling with them and his siblings to Preston, Ireland, and then Llanfairfechan. Here, at age fourteen he worked as a messenger for the London and North Western Railway. As this was usually entry-level work for young boys it is possible he progressed further in the company before the family moved back to Liverpool at some point between 1881 and 1885.

In June 1888, when he was 21 years old Hugh enrolled as an undergraduate theology student at the University of London, however his studies were conducted closer to home at the Liverpool Institute on Mount Street. Hugh was almost certainly the first person in his family to study at a higher level, and although religion was important for many in Liverpool’s Welsh migrant community, there is little to suggest any of the Joneses were especially devout before him.

During his studies Hugh became involved with a woman named Annie Elizabeth Woolrich (b. 12 September 1868, Wybunbury, Cheshire – d. 29 October, 1951), a shopkeeper’s daughter from Cheshire, who became pregnant in the summer of 1889. The two were married in early 1890, a few months before the birth of their son William Ellis Jones on 19 May in Liverpool’s Walton district. In the following year’s census the family were recorded living at 292 Buck Road in Everton. Hugh gave his occupation as ‘tea traveller & student in theology’, confirming that alongside his studies he had been supporting the family through working as a travelling tea salesman.

A nineteenth century engraving depicting a travelling tea salesman (via Alamy).

Later that year, Hugh completed his theology course at the Liverpool Institute and claimed he was ordained by Bishop Baker (or Baxter) of Belmont Road. A year later however, he received a dimissory order for unknown reasons, and in 1894 founded a breakaway sect known as the Evangelical Forward Movement (Free Church of England) with himself as director (The Liverpool Echo, Wednesday 13 May 1896, p. 4, col. 3). This ‘church’ was affiliated with the Providence Orphanage for Fatherless Boys at 63 Newlands Street, of which he was the honorary treasurer.

In 1896 the orphanage (which was actually just a private house in Everton) was rocked by two successive scandals. On 20 March its president Herbert Westworth was acquitted of murdering his wife, following a trial in which it was claimed by the Professor of Medical Jurisprudence at Victoria College that it was “physically impossible” for her wounds to have been self-inflicted. Blood had also been found on a poker, and on Westforth’s clothes (The Northern Echo, 21 March 1896, p. 3, col. 2). The second scandal however implicated not just Hugh himself, but his wife Annie. On 13 May that year, the couple were arrested and charged by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) with the ill-treatment and neglect of William Henry Atkinson, a two-year-old boy in their care. According to a report in The Liverpool Echo:

The child was born in Walton Workhouse, and about five weeks ago was placed in the orphanage. It was understood Mr. Jones was going to take the child and keep it at the orphanage. When the child was sent it was perfectly healthy, clean, and in good condition in regard to clothes and other respects. For some weeks past persons living in the immediate neighbourhood of the defendant’s house had heard crying and screaming and sounds as if children inside the house were being beaten.

Margaret Hazlewood, who took the child to the orphanage five weeks ago, said that when she took it away, it had two black eyes, the nose was injured, the forehead was scarred, and body looked as if there had been a strap or cane used to it.

The Liverpool Echo, 13 May 1896, p. 4, col. 3

The Joneses claimed the boy had obtained all these shocking injuries after accidentally falling downstairs, and after several witnesses gave evidence in support of Hugh’s “high character” the case was dismissed due to lack of evidence. It is unknown what became of boy, but the the Joneses closed the orphanage and fled Liverpool not long after the trial (John Bull, 4 July 1914, p. 8, col. 2).

Report of the charges against Hugh Lloyd Jones and his wife Annie from The Lancashire Daily Post, 14 May 1896, page 4, column 1 (via The British Newspaper Archive).

Following the birth of their first son William in 1891, Hugh and Annie had at least eight more children together. The seven whose names we know were:

- Harold Edgar (b. c. November 1893, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. 22 October 1918, Palestine)

- Albert Woolrich (b. c. May 1896, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. c. August 1956, Birkenhead, Cheshire)

- Arthur Ewart (b. 24 June 1898, Cardiff Glamorgan)

- Hannah Elizabeth G. (b. c. May 1900, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. c. May 1902, Birkenhead, Cheshire)

- Gwenddolen Elizabeth (b. 29 May 1903, Birkenhead, Cheshire – d. December 1990, Birkenhead, Merseyside)

- Leslie Lloyd (b. 3 May 1908, Birkenhead, Cheshire – d. January 1976, Wallasey, Merseyside)

- Phyllis Alice (b. c. May 1914, Birkenhead, Cheshire – d. 7 October 1936, Wallasey, Cheshire)

From their birthplaces it is possible to trace the family’s move from Liverpool to Cardiff in about 1898, then eventually back to Liverpool around 1900, where they were recorded in the following year’s census at 8 Grey Rock Street. Curiously, Hugh gave his primary occupation as a “Publisher of theological works”. He is known to have edited at least one title, Rays From the Welshman’s Pulpit, for the Cambrian Publishing Co. in 1900.

Although the 1901 census made no mention of his missionary work, later reports claim he had opened a new mission in Seacombe that year and sent out a number of collectors:

What became of the money we do not know, but he cleared out without paying his rent and left in debt to a number of tradesmen. He then went to Grange Road, West Birkenhead, where some people were organising what they called “Emanuel Free Episcopalian Church.” He was appointed “Pastor,” and the committee authorised him to collect funds. Failing to account for the amount he collected, he was dismissed. The matter was placed in the hands of a solicitor, to whom Jones admitted receiving and keeping £5 5s. from one subscriber, and £1 1s. from another.

John Bull, 4 July 1914, p. 8, col. 2.

By 1903 the family were living at 40 Dingle Road, Birkenhead, and Hugh was operating a new charitable organisation called the United Church Mission, later known as the Gospel News Mission. Advertisements from late 1903 show services were held at the Co-operative Hall on Catherine Street and then the music hall on Claughton Road, before he established a permanent base of operations at 98 and 100 Price Street. The charity claimed to provide “breakfasts for poor children, parcels for poor widows, Christmas festivities and winter fuel for poor families” (Roddy, Strange, and Taithe, 2019, ch. 4).

The truth however is rather murkier. On 24 January 1906, The Birkenhead News reported that “a coloured man” named Frederick Henry Oxley of 113 Pitt Street, Liverpool, had been summoned by police for collecting alms in Birkenhead Market on behalf of the Gospel News Mission (p. 2, cols. 4-5). Oxley claimed he was being paid “5s. in the £ on all monies collected” and that “free breakfasts were given every Sabbath morning all year round to poor slum children at 10.30 a.m”. He went on to produce a certificate signed by Hugh Lloyd Jones on 20 November 1905 authorising him collect on behalf of the mission, as well as a ledger recording the amounts taken in donations and expenses. On one day however the mission’s expenses were shown to exceed the amount received in donations, leading the prosecutor for the police to call the charity “nothing more than a bogus mission which was carried on for the maintenance of those who ran it, and that it concerned only two or three people—Mr. Jones and his family.”

Report in The Birkenhead News on the ‘alleged bogus mission’ run by Hugh Lloyd Jones at 98-100 Price Street (24 January 1906, p. 2, cols. 4-5 , via The British Newspaper Archive).

The report went on to say that the mission had been under observation on Sunday mornings for some time. Detective Wright, a witness for the prosecution, claimed:

The premises consisted of a large shop with a kitchen at the back. In the shop or mission room there was a table with several seats around it. He had not seen Mr. Jones there, but he had seen a man who was generally engaged as an insurance agent. He had looked into the room on several occasions on Sunday morning between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., and found it empty. At other times he had seen four or five children there. He had seen two or three children at the table eating bread and jam on Sunday morning. From inquiries he had made in the neighbourhood he had found that tickets were sold in connection with the mission at 6d. a dozen, each one of which entitled the holder to get a cup of tea and a piece of bread and butter.

The Birkenhead News, 24 January 1906, p. 2, col. 4.

In addition to the mission’s practice of charging tickets for their supposedly free breakfasts, Wright went on to claim that on one of the few occasions he actually saw children eating there he could not even tell if they were drinking tea or coffee as no milk had been provided. For his part Oxley (described in the report as “a man of considerable intelligence”) claimed to know nothing of the mission’s workings, and had even sought permission from the market’s superintendent before collecting there, thinking it may have been against the rules.

In his defence, Hugh, “a pale black-bearded man of middle age, who was dressed in clerical garb”, complained that he had been blindsided by the case, believing that he had only been summoned as a witness:

“I never thought this attack would be made upon us otherwise we should have been prepared with our solicitors and 200 witnesses to prove the excellent work we are doing in this town.

…

“We have given 2,000 loaves at mothers’ meetings, and we have conducted 200 indoor and open-air services. We have made 60 converts who have professed faith to the Lord Jesus Christ, and it is really an inspiring sight to see these women debauched with drink and living with other men lives of sin giving their testimony as to the power of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Birkenhead News, 24 January 1906, p. 2., col. 5.

Returning to the subject of the mission’s balance sheet, the prosecution alleged that there was a deficit on last year’s working of £49 16s. 8d., approximately £4,000 in today’s money. In an echo of the Providence Orphanage verdict ten years earlier however, the chairman conceded there was insufficient evidence to convict and the case was dismissed. Earlier news reports do appear to support Hugh’s assertion that, for a time at least, the mission had been holding services and providing “a good substantial breakfast of ham sandwiches and a mug of hot tea” for local poor children (The Birkenhead News, 12 December 1903, p. 4, col. 7), however these same articles also prominently featured requests for financial donations.

Just six months later, Hugh was faced with another near-identical charge. Perhaps in response to the bad publicity he received in January, Hugh had founded another mission, the United Christians, in March that year, this time situated amid the slums of Bootle in north Liverpool (The Birkenhead News, 23 June 1906, p. 4, col. 4). Like his previous ‘charitable’ endeavours it was known by multiple names, sometimes being referred to as the ‘Lincoln Mission’ on account of its location at the Lincoln Rooms on Lincoln Street. In a letter to his new landlord however, Hugh expressed his intense dissatisfaction with this new address:

“It is with deep regret I inform you this hall is absolutely useless for Protestant services. We are being considerably annoyed at every meeting by young people and others in Lincoln-street. I have worked very hard to try to get up meetings, but the district is essentially Romanish, and no respectable people will come to Lincoln-street to be annoyed. On Good Friday we had a lantern entertainment, and lost 10s. on the transaction.

“Not one penny have I had from those who have attended at the hall. The room is not worth the money expended upon it, and I now quite understand why it was so long untenanted.”

The Birkenhead News, 23 June 1906, p. 4, col. 4.

Hugh’s apparent annoyance at his own decision to set up an evangelical mission in a primarily Irish Catholic district aside, the main purpose of the letter was to explain his inability to pay rent. He went on to complain that after sending off a hundred letters seeking donations he had received only 20s., which barely covered his postage costs.

On 22 June 1906 Hugh appeared at Dale Street police court following a summons for having “aided and abetted a dark-coloured man named Prince Frederick Bailey in the practice of begging.” Bailey, a former ship’s steward and cook from Kingston, Jamaica, had been arrested for seeking subscriptions for the Lincoln Mission at 15 Croxteth Road on 15 June. Inevitably this was traced back to Hugh, who was once again accused of running a bogus charity. It was noted that there was no record of any expenditure on upkeep in the mission’s account books, nor receipts for at least two known donations from prominent Liverpool shipowners, but again the case was dismissed due to lack of evidence and the mission closed voluntarily soon after. In his closing remarks the presiding magistrate condemned both Hugh’s financial activities and (perhaps surprisingly) the credulous public who enabled men like him:

“If people knew that nine-tenths of the money they gave was going into the pockets of the proprietor of the mission and his collectors, they might not be so ready to give contributions. We can’t prevent the public from making fools of themselves by giving money to institutions which they know nothing about. Yet there are institutions like the Children’s Infirmary which cannot be built because the people of Liverpool have no money to give—they prefer to fritter it away on things of this sort. You can’t protect the public from their folly.”

The similarities with the previous allegation against Hugh are striking enough to suggest a pattern. In both cases he was accused of seeking to obtain money under false pretences, following a complaint about one of his collectors. In addition, although Liverpool had an established African-Caribbean community by the early twentieth century it is notable that on each occasion his collector was described as a Black man with the name Frederick. This could be a coincidence but the fact that no record can be found of a ‘Frederick Henry Oxley’ in Liverpool at this time suggests this may have been a pseudonym of the man identified as Prince Frederick Bailey in the second case. If true, this would hint at a long-standing association with Hugh and his dubious organisations, rather than the kind of casual relationship implied in the news coverage. How such an association may have arisen is unclear, but according to census records Prince Frederick Bailey would have been in his sixties by 1906, and so could have been driven into Hugh’s orbit through poverty and a lack of opportunities elsewhere (the repeated and gratuitous references to his skin colour in the press coverage attests to the widespread racism of the period, which would erupt in a spate of anti-Black race riots in Liverpool and other port cities in the summer of 1919). By 1911 Prince Frederick was an inmate at the Liverpool Stanley Hospital for the treatment of diseases of the chest, and died just two years later in 1913 at the age of seventy.

Following the failure and exposure of the Lincoln Mission it is believed Hugh moved his operations to 67 Cambridge Road, Bootle, and Derby Road, where he had elaborate notepaper headed “The Parsonage” (John Bull, 4 July 1914, p. 8, col. 2). By 1907 however he had returned to Birkenhead, this time to 66 Queen’s Road, and it was around this time he began signing his name ‘Hugh L. Jones’. Whether intentional or not, this ‘rebrand’ intensified an already bitter rivalry with a fellow charity operator named Herbert Lee Jones, whose initials he shared. According to Sarah Roddy, Julie Marie Strange, and Bertrand Taithe in The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, 1870–1912 (2019):

In March 1908 the Reverend Hugh Lloyd Jones (Lloyd Jones), Birkenhead, warned Herbert Lee Jackson Jones (Lee Jones), Liverpool, that he intended to sue him and his printer for defamation of character and libel. Lee Jones invited the reverend to ‘proceed at pleasure’ and forwarded the name and address of his solicitor. The legal threat was the culmination of a three-year feud between the men, much of which Lee Jones conducted through his charity’s journal, The Welldoer, and letters to the local press.

Lee Jones’s chief accusation was that Hugh’s status as a minister was fraudulent, and that his various missions (which were often known by more than one name concurrently and were linked to no recognised denomination) had just been vehicles for his personal enrichment. In addition to its history of dubious hiring decisions (including a barely literate committee member, a convicted bogus charity collector, and Hugh’s nineteen-year-old son William, a grocer’s assistant, as honorary treasurer), much of Lee Jones’s criticism focused on the mission’s account-keeping. In particular he took issue with the way the charity’s purported aims of providing meals and outings for poor children were classed as ‘general expenses’ alongside any number of vague running costs, including Hugh’s rent and fuel. In practice, this meant it was impossible to verify how much money was being spent on charitable work, and how much effectively ended up in Hugh’s pocket. In addition he observed that the accounts were signed off by internal ‘committee’ members, rather than external auditors. Despite his best efforts though, Lee Jones was unable to secure a fraud conviction because Hugh was able to prove that at least some of the money the mission raised was spent on charity work, albeit a “paltry percentage”.

Although Hugh’s Gospel News Mission was only one of six local charities ‘blacklisted’ by Lee Jones, he took particular interest pursuing Hugh because their similar names risked them being confused in the public mind. After failing to bring his case to the courts, Lee Jones turned his attention to trashing Hugh’s reputation in his journal The Welldoer. This proved so successful that by 1907 Hugh required police protection while collecting funds in Birkenhead Park due to public hostility. This would undoubtedly have been a contributing factor in his decision to sue Lee Jones for libel the following year, and his bitter words at the time attest to the personal animosity between the two men:

Who he asked, had authorized Lee Jones as ‘cock of the walk’ to legitimate charities? Charitable ‘fraud’ was subjective and Lloyd Jones exercised ‘no more tomfoolery’ in philanthropic endeavour than Lee Jones ‘or anyone else’. It was ‘scandalous’ that Lee Jones should accuse him of fraud while ‘squandering’ the funds of the LWD and failing to publish a list of subscribers. The LWD ran highly successful fundraising bazaars: what, asked Lloyd Jones, happened to all that money?

Sarah Roddy, Julie-Marie Strange, and Bertrand Taithe (2019)

Hugh’s attempt to deflect attention from his own charity to Lee Jones’s was not without some justification, as the League of Welldoers (LWD) had also been under investigation by the Charity Organisation Society due the large number of debts they had amassed. Ultimately however, they found no evidence of wrongdoing on Lee Jones’s part and the LWD remains an active charity to this day. Like Lee Jones’s fraud allegations against him, Hugh’s libel claim did not result in legal proceedings and both men remained free to continue operating, but there is no question Hugh’s reputation suffered even further as a result of this painful and protracted rivalry.

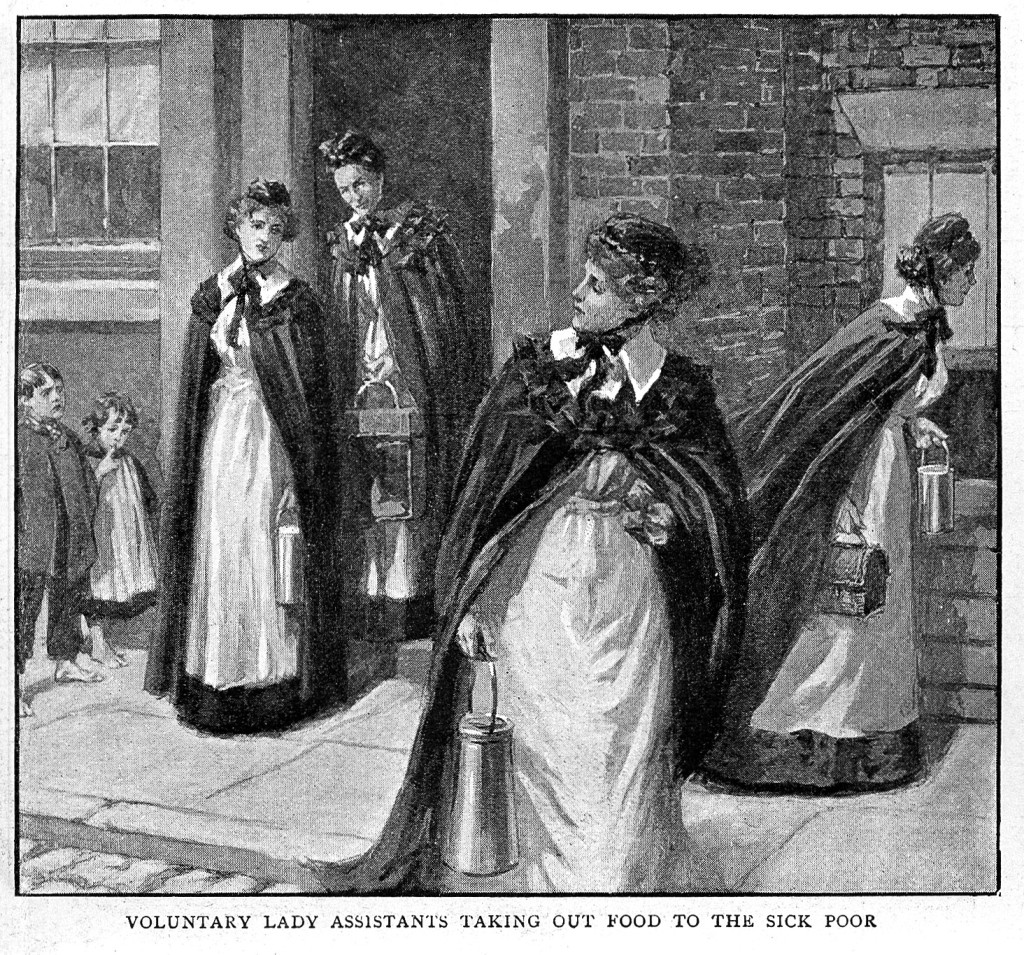

Illustration showing volunteers from the Liverpool Food and Betterment Association (later the League of Welldoers) taking food out to the sick poor, published in The Graphic, August 26 1899. Source: The Wellcome Collection (via Wikimedia Commons).

Blank contribution slip from Herbert Lee Jones’s Food and Betterment Association, featuring his name at the bottom (via Liverpool University Press).

Hugh’s last two notable appearances in the local press both date from 1914. The first was in February that year, when he stood unsuccessfully as a candidate in a Birkenhead Board of Guardians election. The published results show he came last with only 70 votes, 615 fewer than his nearest rival (Liverpool Evening Express, 28 February 1914, p. 5, col. 2), which is perhaps a good indication of his standing in the community by then. His second appearance came in a scathing article in the populist John Bull magazine entitled “A “Reverend” Rascal”, which catalogued his “astonishing record of chicanery” and asked “will the authorities move?” (John Bull, 4 July 1914, p. 8). The article serves as an obituary for Hugh’s scandal-ridden career, including a chronology of his alleged misdemeanors to that point, challenging him on his qualifications, and calling out his latest activities at ‘St. Jude’s Mission Church’, Birkenhead, which the magazine’s investigators revealed to be nothing more than a two-room slum in a disused pub on Chapel Street. When asked where the mission’s supposed home for poor children was, Hugh named a cottage in Moreton about five miles outside Birkenhead, which unsurprisingly turned out to house no children at all. The article went on to describe an extraordinary scene at Birkenhead Park where Hugh was giving an open-air sermon later that evening:

Mr. Jones’ platform was a van, placed close to the Park Gates, upon which was a portable pulpit. His supporters on the van consisted of two elderly women, two younger ones, and a couple of little girls. His congregation numbered less than a dozen. By way of commencement, Jones–who was in full clerical attire–took off his top hat and donned a college cap. A tremendous laugh greeted him from another open-air meeting some fifty yards away. This gathering was attended by at least two thousand people, and being curious to know what the attraction was our representative made his way towards it. The speaker turned out to be a well-known local man, and the meeting was one of protest against the Rev. H. Lloyd Jones exploiting the poor of Birkenhead for his own benefit.

John Bull, 4 July 1914, p. 8

Perhaps with this very public humiliation Hugh realised the game was finally up, as after 1914 he appears to have drifted into obscurity. It appears that he returned to Preston for a time where he was the incumbent at St. Philip’s Church (The Lancashire Daily Post, 10 September 1917, p. 6, co. 1). In 1921 when the family were living at 14 Rostherne Avenue, Wallasey, he recorded his occupation as a Free Church Minister “without pastoral charge”, and there are no known reports about his activities at this time. His son Harold was killed in 1918 fighting in Palestine, his youngest daughter Phyllis passed away in 1936, and at eighty one Hugh himself eventually died of renal uraemia and a hypertrophied prostate at Victoria Central Hospital, Wallassey, on 9 February 1948. The three of them, along with Hugh’s wife Annie, who outlived him by four years, are buried at Rake Lane Cemetery. The question of whether or not Hugh was ever drawn to religion or charity work for genuine reasons is moot. Even if his ‘missions’ ended up helping a number of people, the decades of corroborating allegations against him make it difficult to view him as anything other than a self-interested con-man. For years he succeeded in exploiting the people of Liverpool and Birkenhead by appealing to their sense of Christian charity at the peak of the Welsh Revival (which spilled over into Liverpool and Birkenhead’s Welsh community), and if he can be said to have a legacy, it is as a pioneering scammer.

Headstone of Hugh Lloyd Jones, his wife Annie, and his children Phyllis Alice, and Harold Edgar Jones, Rake Lane Cemetery, 2021. Courtesy of S. Potts-Bury.

* * *

It is unknown to what extent Hugh’s wider family were aware of his activities during this period, whether they supported him for his apparent piety and the money he brought in, or shunned him for the succession of scandals into which he dragged their name. Although his father John died before Hugh began ministering, his mother Hannah lived until 1927 so must have had at least some knowledge of his career. As for his nine known siblings (the 1911 census records that Hannah had twelve children in total, two of which had died by then), most lived fairly ordinary lives compared to him. John and Hannah’s second child Harriet Elizabeth Jones (b. 21 October 1868, Bootle, Lancashire) married a Welsh shipbuilding engineer’s machine fitter named James Davies (b. c. 1869, Denbigh, Denbighshire) on 16 May 1892. Later censuses show they lived at 63 Emery Street (1901), 120 Bardsay Road (1911) in Walton-on-the-Hill, and 16 Windermere Street (1921), Everton, and that they had at least six children together, including:

- Florence Edith (b. 17 June 1897, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. November 1984, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Ernest Henry (b. 19 April 1900, Liverpool, Lancashire)

The 1921 census shows that James had been employed as a mechanical engineer by Cammell Laird & Co. Ltd. of Birkenhead, the world famous shipbuilders who were responsible for constructing many of the Royal Navy’s warships and submarines during World War I. His son Ernest was also working there part-time as a mechanic while enrolled as a medical student at the University of Edinburgh. James died at some point before the outbreak of the Second World War, with the 1939 register showing Harriet living alone at Newsham House on Newsham Drive, and her last known address is said to have been at 3 Grassmere Street. She died at the age of 82 in 1951 and was buried on 27 March at Anfield Cemetery. Unfortunately little else is known about her or her descendants.

John and Hannah’s third child Robert Thomas “Bob” Jones (b. 27 June 1871, Preston, Lancashire) was shown in the 1891 census working as a clerk in the sea trade at age twenty, when he was still living with his parents at 18 Brae Street. There were many well-known shipping companies trading in Liverpool at the time for whom he may have worked, including White Star Line and Cunard. Three years later he married Elizabeth Jane Kent (b. 2 December 1865, Toxteth, Lancashire) on 2 September 1894 in Everton, witnessed by his younger brother John. Their marriage certificate confirms Bob was living at 5 Whitefield Terrace and Elizabeth at 13 Chrysostom Street, and that he was employed as a bookkeeper.

By 1897 however Bob was recorded as a commercial traveler in his second daughter’s baptism record. He and Elizabeth had a total of three daughters together between 1895 and 1900, whose names were:

- Eleanor Gladys (b. c. February 1895, Everton, Lancashire)

- Lilian Gertrude (b. 6 March 1897, Everton, Lancashire)

- Phyllis May (b. 21 January 1900, Anfield, Lancashire)

The girls’ baptism records reveal the family lived at a number of addresses, including 17 Apollo Street in Everton in 1897, and 20 Springbank Road, Walton-on-the-Hill in 1900, where they were also recorded in the following year’s census. By 1900 Bob had left his white-collar job and was working as a wood turner for a ‘timber establishment’, like his father before him. This was also his stated occupation in 1911, when the family were living at 509 Prescot Street in the curiously-named neighbourhood of Old Swan. That year his eldest daughter Eleanor was employed as an operator for the National Telephone Company, a career she and her sister Phyllis held as late as 1939 when they were living with their parents at 58 Sandstone Road, which had been the family home since at least 1921. It is unclear what happened to the family after the war, however my grandmother recalled an ‘Uncle Bob’ coming to visit his younger brother William Arthur in the Isle of Man when he would have been in his seventies or eighties.

Bob’s unusual career trajectory from commercial traveler to self-employed wood turner by 1921 may at first seem surprising, but the Joneses clearly had a deep and longstanding connection to the trade. Most of John and Hannah’s male children worked as wood turners or in related occupations at one point or another, and the first do do so was their fourth child John Owen Jones (b. 23 August 1873, Athlone, Roscommon). John, or “Jack” as he was known (presumably to distinguish him from his father), was born in Ireland during the family’s brief stay there in the 1870s, and by the time he was eighteen was working as an apprentice turner in Liverpool, perhaps for his father. Three years later he married a warehouseman’s daughter named Mary Harriet Horley (b. 10 February 1875, Liverpool, Lancashire) in about August 1894, and by 1897 they had moved to Denbigh in North Wales. They later relocated to Llanrwst where they were recorded living at 3 Salisbury Terrace in 1901. They had at least five children together, including:

- Winifred Amy (b. c. November 1894, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Albert Richard (b. c. 1897, Denbigh, Denbighshire – d. 14 July 1916, France)

- Wilfred Arthur Owen (b. 2 April 1906, Liverpool Lancashire – d. October 1992, Lichfield, Staffordshire)

- Norman Clifford (b. c. August 1911, Liverpool, Lancashire)

The children’s birthplaces suggest the family moved back to Liverpool at some point between 1901 and 1906, specifically to 8 Ludwig Road in the district of Walton-on-the-Hill near where Jack’s older sister Harriet’s family were living at the time. The 1911 census reveals that by then Jack was no longer employed as a wood turner, and was instead recorded working as a yard foreman at a confectionary works. Unfortunately it is unknown which confectionery company he worked for at the time, but one of many possibilities is Crawfords biscuit factory on Binns Road, which was less than an hour’s walk away from Ludwig Road. The fact that his daughter Winifred was that same year working as an assistant overseer at a ‘biscuit works’ would seem to support this hypothesis, however if this was the case it is odd Jack did not describe his own place of work in the same terms.

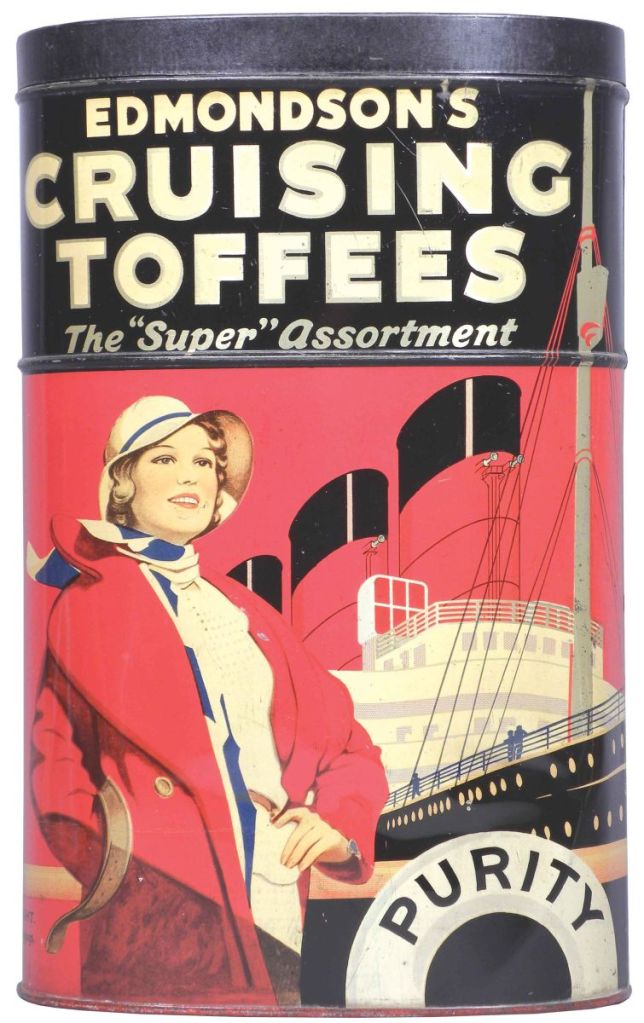

Whoever he was working for in 1911, the 1921 census confirms that by then he was employed as a commercial traveller for Edmondson & Co. Ltd. Purity Brand Works, a confectionery company based of 50 Fox Street, about half an hour away from the family’s new address at 91 Hornsey Road. Edmondson’s had been in business since 1905, so it is entirely plausible Jack had been working for them at the time of the 1911 census too. He appears to have stayed in a similar line of work thereafter, as in the 1939 register he was recorded as a ‘commercial traveller (sugar)’, possibly for Tate and Lyle who had a factory in Vauxhall near where he and Elizabeth’s were then living at 31 Crosby Green. It is not known when or where he died, but his brother William Arthur’s family remember him coming to visit occasionally on the Isle of Man in the 1950s, where the two brothers are said to have enjoyed paddling at the beach together with their trousers rolled up.

Site of Edmondson’s confectionary works on Fox Street, 2013 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Jack was not the only one of his siblings to work in the confectionery industry. His younger sister Margaret Anne Jones (b. 30 July 1875, Athlone, Roscommon), John and Harriet’s fifth child, had like him been born while the family were in Ireland. At sixteen she was apprenticed as a dressmaker, and in 1898 she married Francis Carr Brown (7 May 1875, Liverpool, Lancashire) when she was twenty three. Together hey had three children, two of whom survived infancy:

- Francis Edgar (b. 10 March 1901, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. c. January 1947, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Doris (b. c. 1903, Liverpool, Lancashire)

The 1901 census shows them living at 6 Handfield Place in Everton. Francis Sr.’s occupation was recorded as ‘fruit selector’, which likely meant he was employed by a company like a jam or sweet manufacturer to buy fruit from wholesalers for use in their products.

Sadly Francis died just six years later in 1908 at the age of thirty three. His burial record from West Derby Cemetery gives his last occupation as ‘porter’ and his residence as 15 Lowell Street in Everton. Margaret, suddenly a widow at only thirty two, now faced the terrible challenge of paying rent and feeding her family with no source of income. The 1911 census reveals that following her husband’s death she had moved back in with her mother and younger brothers David and George at 40 Landseer Road. Although she had managed to find work as sweet packer by then (perhaps at Edmondson’s with help from her brother Jack), unfortunately her earnings would not be enough to support her children.

Her eldest son Francis Edgar Brown was sent to Wavertree Cottage Homes for pauper children, which was administered by Liverpool Workhouse. It is uncertain what happened to his sister Doris, however the 1911 census records a patient with her name at convalescent home for children in West Kirkby. In 1916 Francis enlisted in the 7th Liverpool Regiment at the age of just fourteen (a year younger than he claimed) and served in the territorial army. His service record shows that by 1916 he was back living with his mother at 83 Stockbridge Street, where they were recorded in the 1921 census alongside Margaret, her brother George, George’s son Arthur, and Doris. By this time Francis was employed as an army clerk for the 1st King’s Liverpool Regiment, and Doris (continuing the family’s association with confectionary) was working as a ‘chocolate dipper’ at the Sunbeam Chocolate Company. After this date Margaret and Doris’s fates are unknown. Francis would go on to marry a woman named Alice Fulford, but like his father died young at the age of forty five.

* * *

John Ellis Jones and Hannah’s sixth child was my great-grandfather, William Arthur Jones, to whom I will return later. Their seventh child Hannah Roberts Jones (b. 17 April 1880 Llanfairfechan, Caernarvonshire) was born after the Joneses’ move form Ireland to Wales, but before their return to Liverpool in the early 1880s. At twenty one she was employed as a chair mattress maker, and two years later she married Hugh Lorin Jones (b. c. May 1874, Garston, Lancashire, no relation), with whom she had at least one daughter:

- Jane (b. c. 1908, Liverpool, Lancashire)

The 1911 census records that Hugh was an engineer by trade, but his place of work is said to be a ‘confectionary works’, clearly connecting Hannah’s branch of the family with those of her elder siblings Jack and Margaret. It is possible Hugh had been one of her brother Jack’s workmates at Edmonton’s confectionary works, or perhaps Hannah had briefly worked alongside him at the same factory before they were married. The family’s address at 22 Columbia Road in Walton-on-the-Hill places Hannah in the same general area as Jack and Margaret, further strengthening the link. Their whereabouts at the time of the 1921 census are unknown, but by 1939 Hannah was widowed and living at 43 Rockley Street with two lodgers. She passed away at the age of seventy eight and was buried on 2 August 1958 in Kirkdale Cemetery.

David Lloyd Jones (b. 31 March 1885, 150 Breck Road, Everton, Lancashire), the eighth of John and Hannah’s children, appears to have been part of this same tight-knit group of siblings. Like many of his brothers, he had been apprenticed in a woodworking trade as a boy, and was recorded as a cooper in the 1901 census. By 1911 however he was employed as a shipbuilder’s fitter, perhaps working alongside his brother-in-law James Davies at Cammell Laird & Co.. That year he he was living with his mother at 40 Landseer Road, along with his recently-widowed sister Margaret, his younger brother George, and his new wife Florence (b. 6 July 1883, Everton, Lancashire). David had married Florence Jane Gamblen, the daughter of a ship’s cook, two years earlier in 1909. The following year Florence had given birth to their first child, a daughter they named Vera Hannah Jones (presumably after David’s mother). Sadly Vera died shortly before her first birthday, and was buried on 7 March 1911, just four weeks before the census was taken.

David and Florence had a total of seven children together between 1910 and 1926, whose names were:

- Vera Hannah (b. 14 May 1910, Liverpool, Lancashire – bur. 7 March 1911, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Thomas William (b. c. February 1912, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. 24 February 1935, Stanley Hospital, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Hilda May (b. 30 December 1914, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. 27 April 2006, University Hospital, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Iris Edna (b. 15 Jun 1916, Everton, Lancashire – d. 4 January 1996, Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, Somerset)

- David Lloyd (b. 3 July 1918, Northwich, Cheshire – d. 2 June 2013, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Elsie Winifred (b. 19 January 1922, West Derby, Lancashire – d. 3 May 1987, Halton, Cheshire)

- Doreen Florence (b. 2 March 1926, West Derby, Lancashire – d. 24 July 1943, Newton, Lancashire)

Their second child Thomas also died prematurely at the age of twenty three. According to his probate record, his effects valued at £5.15 went to a ‘David Jones packer’, which was probably a reference to his younger brother rather than his father. This same record gave his address as 341 Cherry Lane, the same semi-detached house in Liverpool’s northern suburbs where his parents and siblings Hilda, David, Elsie, and Doreen were all living at the time of the 1939 register. David Sr.’s occupation, ‘Engineering fitter’, is consistent with that which he gave in earlier censuses, and a photograph from 1951 shows him and Florence at an ‘A.E.U. Liverpool’ outing, presumably an abbreviation of the Amalgamated Engineering Union.

With the exception of Doreen, who unfortunately passed away when she was seventeen, the rest of David and Florence’s children lived long lives and have multiple living descendants, many of them in and around Liverpool. Florence died at the age of seventy eight in 1961, followed five years later by David on 1 May 1966. He was eighty one. Both he and Florence were interred at Anfield Cemetery in the same plot as their children Thomas and Doreen.

After David, John and Hannah’s ninth child was another son, Herbert Ellis Jones (b. c. November 1886, Liverpool, Lancashire). Like his eldest brother Hugh, Herbert’s first job was as a railway messenger when he was fifteen. At twenty one he was married to Theresa Maria Perrin in early 1907, with whom he had two boys and two girls:

- Herbert Lindsay (b. 16 August 1908, Liverpool, Lancashire – d. July 1953, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- William Stanley (b. 31 July 1910, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Hilda (b. 16 October 1912, Liverpool, Lancashire)

- Margery (b. 11 November 1914, Liverpool, Lancashire – 1995, Torbay, Devon, England)

In 1911 the family were living at 39 Grange Street along with Theresa’s younger brother John, who like Herbert was working as a house painter. Shortly after they moved to 25 Curate Road, where they were recorded at the time of their second daughter’s baptism in 1914 (which unusually for the Joneses was a Church of England ceremony). At some point over the next three years, like millions of other men his age Herbert enlisted or was conscripted to fight in the Great War. His service record has not survived so it is unknown precisely when or where he signed up, but he is known to have served on the Western Front as a private in the maxim gun section of the the King’s Liverpool Regiment, and was later transferred to the 46th Division of the Machine Gun Corps Infantry Branch.

Machine gunners of the King’s Liverpool Regiment, 7th Battalion (via ww1photos.org).

Unfortunately the only reason these details are known at all is because he was killed in action in August 1917. Given the date it is likely this occurred during the Third Battle of Ypres (also known as the Battle of Paschendale), a muddy four-month-long campaign which cost both sides over half a million lives between them, and resulted in a fairly limited Allied victory. A notice in The Lancashire Daily Post (10 September 1917, p. 6, co. 1) reported his date of death as 28 August, while his army pension record gives August 30, suggesting that no one really knew for sure. His body was probably never recovered, but he is commemorated at Aeroplane Cemetery in Belgium. Herbert’s widow Theresa never remarried and died thirty years later on 3 March 1947. Of their children it is said the two boys later developed cancer as a result of working on leaded glass windows for churches, but today their descendants and those of their sisters can be found all over the country.

Like Herbert, John Ellis and Hannah Jones’s tenth and last child George Edwin Jones (b. c. August 1889, Liverpool, Lancashire) was a house painter by trade. From the age of eighteen however he is also known to have been a part-time volunteer with the British Army’s Territorial Force since its creation in 1908. The Territorial Force had been established to bolster the country’s home defence in the build up to World War I without resorting to conscription, but was not generally considered to be a success. Records show George was with the 6th Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment until 30 April 1908, and then later the 1st West Lancashire Field Ambulance to 31 March 1912. Volunteers generally signed up for a four-year-term but were not compelled to serve overseas.

As the youngest in the family George was unsurprisingly still living at home with his mother at this time. The 1911 census records him at 40 Landseer Road alongside his older siblings Margaret and David, plus David’s wife Florence. At some point over the next three years he became involved with a woman named Gertrude Thomas, who he married at West Derby Road Registry Office on either 6 June or 13 July 1914. Whatever the exact date, it is certain that at the time of their wedding Gertrude was about four or five months pregnant. This possibly accounts for why the couple opted for a civil ceremony at a register office rather than a religious one, as well as the uncertainty over the date (the later one could have been an unofficial ‘public’ wedding after the official private one).

Their honeymoon period could only have lasted a matter of weeks however, as on 4 August Britain declared war on Germany and as a former Territorial Force volunteer George was one of the first to enlist (his service record shows his service actually commenced a day before the official declaration of war). He gave his address as 83 Stockbridge Street, and his occupation as ‘unemployed painter’, which perhaps explains his eagerness to sign up as early as possible. The following day he passed the medical inspection (which gave his height as 6’1/2″ and rated both his vision and physical development as ‘good’) and he was duly appointed to the 9th Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment with the rank of private. Three months later, Gertrude gave birth to their son, who they appear to have named after one George’s older brothers:

- Arthur (b. 1 November 1914, Liverpool, Lancashire)

Inspection of the King’s Liverpool Regiment (the ‘Liverpool Pals’) by Lord Kitchener in front of St. George’s Hall, Liverpool, 20 March 1915 (via Wikimedia Commons).

George’s military service appears to have taken place mostly away from the frontline in England, apart from a six-month stint as part of the Expeditionary Force France between 12 March and 11 September 1915. This was at least in part due to the fact that on 20 July 1917 he was compulsorily discharged on account of disability. According to his service record, by this time George was suffering from rheumatism, an intermittent chronic pain disorder affecting the joints which would have rendered him no longer suitable for combat. He applied for munitions work in Liverpool before being officially transferred to the to the Western Command Labour Centre on 30 July, whose role was to was to coordinate the supply of labour to the Western Front. He was briefly attached to the Reserve Employment Company on 7 September and then assigned to the Royal Army Medical Corps four days later, perhaps due to his experience in a Field Ambulance unit before the war.

George remained with the RAMC for the duration of the Great War, and after the armistice was part of the army reserve. He was awarded the British and Victory Medal on 7 March 1922. The previous year’s census shows he had returned to his peacetime occupation as a house painter, this time as an employee of the firm David Rollins & Sons. He was still living at his mother’s three-room-house at 83 Stockbridge Street, along with his sister Margaret, her children, and his seven-year-old son Arthur (Gertrude appears to have been elsewhere on census night). The family family later lived at 17 Rossett Street, Liverpool, and Seacombe in Wallassey according to George’s army pension records, but it is currently unknown when or where they died or if they have any living descendants.

* * *

When looking into the lives of John Ellis and Hannah Jones’s children, a clear picture emerges of a family connected through a common geographical range centred on Walton, Everton and Anfield, plus shared occupations in wood turning, shipbuilding, house painting, and confectionary. Many of them lived under the same roof well into adulthood, and some even served in the same military regiment in World War I. The notable outlier would appear to be their ‘rogue’ elder brother Hugh Lloyd Jones, whose high-profile ministerial work seems to set him apart from the rest of his siblings, with one possible exception.

My great-grandfather, John Ellis and Hannah Jones’s sixth child, was born on 9 August 1877 in the Irish town of Sligo, at the family home on Charles Street. He was baptised William Arthur Jones but later often went by just Arthur or ‘W.A.’ When he was around two the family left Ireland for Wales, where they remained for a few years before settling in Everton when Arthur would have been about seven. As a youth he is said to have been among the crowds witnessing the first motor car drive through Liverpool, and unusually for a boy from his background received private Latin lessons at 6 d. per hour. A possible explanation for this is that his older brother Hugh was beginning his theological studies at the Liverpool Institute around this time, which may have sparked the younger son’s interest in academia.

Although his parents appear to have supported Arthur’s early educational ambitions, the family’s immediate material needs took precedence. He left school when he was twelve and began an apprenticeship as a wood turner, an occupation he shared with both his father and brother Jack at the time of the 1891 census. After his father’s death the following year, Arthur continued working as a turner until 1901, by which time he was was the oldest of his siblings living with their mother at 17 Apollo Street. Later that year however, at the age of twenty four he began preaching as a Wesleyan Methodist minister in Pontypridd, South Wales. The following April, his name was recorded in the local press for the first time, having given “a very stirring address” at the Wesley Hall for a meeting for showpeople connected with the Easter fair (Pontypridd Chronicle and Workman’s News, 12 April 1902, p. 8, col. 1).

On 8 September that year, Arthur officially enrolled as a student at the Wesleyan Theological Institution in Didsbury, Manchester, where he studied for three years before graduating on 22 June 1905. At this time Wesleyan ministers were obliged to relocate to new ‘circuits’ every three years (in order to reflect Jesus’ original three-year ministry), and as a result Arthur’s life hereafter was one of almost constant travel. After Pontypridd, his first position as an ordained minster in late 1905 was at was Barrow-in-Furness in Cumberland, where he stayed for two years before moving to Kendal for the final year of that ministry.

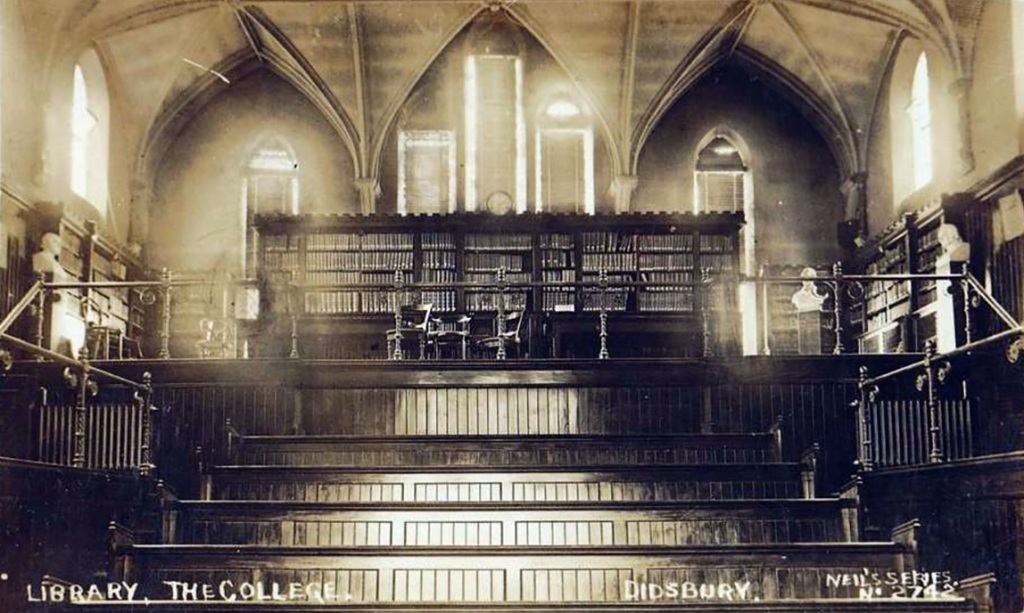

The Library at the Wesleyan Theological Institution, Didsbury, 1911 (via Wikimedia Commons).

In 1908 Arthur returned to South Wales to minister at the Roath Road circuit in Cardiff. Around this time he begun a relationship with a woman named Agnes Rowlands (b. 2 June 1880, Penygraig, Glamorgan), a Welsh-speaking twenty-eight-year-old school teacher and daughter of a local colliery proprietor, who had also gained a reputation as an excellent singer. Agnes had been living at Pontypridd when Arthur was ministering there in 1901, so it is entirely possible the two had known each other since then, perhaps corresponding by letter in the intervening years. They were married on 20 August 1908 at Saron Calvinistic Methodist Chapel, Treforest, by Agnes’s brother-in-law the Reverend David Richards.

Immediately after their marriage Arthur begun preaching at Caerphilly. Here, according to their friend W.T. Tilsley (who Arthur trained as a young man) “he made a deep and lasting impression by his outstanding pulpit gifts”:

He was indeed a great preacher and every sermon was most carefully prepared and delivered with “Welsh fervour” … He had a keen logical mind and impressed me with the necessity of orderliness in the presentation of my ideas … I may say that I owe more to W.A. in the field of homiletics than to any college professor, some of whom though great scholars had no idea how to preach”

W.T. Tilsley, 31 August 1960.

They were still at Caerphilly the time of the 1911 census, living at Mountain View, the manse at 63 St. Martin’s Street. A far cry from the houses Arthur has known as a boy in Liverpool, it had nine rooms in total excluding kitchens, halls and bathrooms. They even employed a domestic servant named Janet James. By this time they had also been joined by an infant daughter:

- Evelyn Mabel (b. 19 October 1909, Caerphilly, Glamorgan – d. 7 January 1993, New Zealand)

That same year Arthur was described in the 1911 Methodist Conference Handbook as “a careful student possessing a sympathetic knowledge of theological and social problems, together with real preaching ability,” suggesting his reputation as a gifted speaker was beginning to spread.

Later in 1911 Arthur was assigned to the Bilston circuit in Staffordshire. Here he, Agnes, and Evelyn stayed for a while with Agnes’s brother Moses at Wesley Manse, Ettingshall, before moving to Wednesbury in 1914. As a minister of religion Arthur was exempt from military service in World War I, and would have been forty years old when news of his brother Herbert’s death at Ypres reached him. At Wednesbury he was said to have “won for himself a good reputation as preacher and pastor and done some excellent work for the Sunday Schools” (Royal Leamington Spa Courier and Warwickshire Standard, 30 August 1918, p. 2, col. 1).

In 1918, the last year of the war, the family moved to Royal Leamington Spa in Warwickshire. At a welcome reception held for him at Dale Street Wesleyan Church Arthur gave a brief address intimating that he had come to Leamington to do his best, but that “as a result of four years’ war the church would be severely taxed” (Royal Leamington Spa Courier and Warwickshire Standard, 6 September 1918, p. 2, col. 3). After the Armistice, he is reported having preached at the same church the following year using “He Is Our Peace” as his text. He emphasised that “it was through God alone that our victory was secured” (Royal Leamington Spa Courier and Warwickshire Herald, 11 July 1919, p. 8, col. 5). Two years later Agnes gave birth to their second child, my paternal grandfather:

- Rowland Bevan (b. 18 January 1920, Trinity Church Manse, Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire – d. 8 May 2000, Ramsey Cottage Hospital, Ramsey, Isle of Man)

After three years in Royal Leamington Spa the family moved to Hainton Avenue, Grimsby, in 1921, but after 1924 the rest of Arthur’s working life was spent in Yorkshire. Their first address in the county was at 24 Wellesley Road in Sheffield, when Arthur was ministering at Carver Street Chapel in the city centre. Later in 1928 he preached at Firth Park Chapel on Ellesmere Road, near their new home at 262 Abbeyfield Road. By now his daughter Evelyn had begun working as a colliery secretary in nearby Rotherham, and Rowland was attending Firs Hill primary school. According to his obituary it was in Sheffield where Arthur did arguably his greatest work, having “built an institute and inspired hundreds of young people to serve Christ”, training up many new preachers through his homiletical classes. The teaching of others had always clearly held special importance to him, as one of his earliest students attests:

The last thing he said to me when he left Caerphilly in 1911 when I tried to thank him for all that he had done for me, was “Don’t thank me, but try and do for other young men what I have done for you.” And that I have sought to do all through my ministry and thank God, have succeeded.

W.T. Tilsley, 31 August 1960.

The Joneses left Sheffield in 1931 and resettled in the market town of Batley, where Rowland attended the local Grammar School. At the end of Arthur’s three-year-ministry they moved to Huddersfield, where Arthur preached at the chapel on Buxton Road and Evelyn worked for an organ building firm. Like her mother and a number of aunts on the Rowlands side, Evelyn was quite musical and was both a gifted singer and pianist. Rowland meanwhile, who was ten years younger than Evelyn, attended Huddersfield Grammar School where he was awarded Higher certificates, and then progressed to Huddersfield Technical College in 1937. He studied science subjects here for one year and won a town scholarship of £50 per year for six years. In 1938 he enrolled to study Medicine at the University of Leeds, conveniently near where the Joneses were then living at Brunswick House (Morley Manse) on Worrall Street, in the city’s south-western suburbs.

When war was declared on Germany for the second time in Arthur’s life on 1 September 1939, Rowland was nineteen and thus would usually have been eligible for military service. His student status however made him temporarily exempt and he was allowed to complete his studies. The same month war was declared, Evelyn married George Mason Smailes (b. 23 January 1916, Huddersfield, Yorkshire – d. 23 October 1988, New Zealand). They moved to London shortly after where George worked as a policeman during the blitz. They they would go on to have three children together over the next five years.

Meanwhile Arthur and Agnes continued to travel around the Yorkshire circuits, although with less frequency than before as in 1933 the Methodist Church had amended their rules to allow for five year ministries. In 1941 they moved to Farnley, and then to Pudsey within the city of Leeds in 1943. Around the time of this last move Rowland had completed his degree (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) and graduated with honours. The 1947 Medical Register states that he was registered on 31 March 1943 in Bradford. His first job was as house surgeon to the Professor of Surgery at the University, before moving to Leeds General Infirmary where he was later appointed Casualty Officer responsible for treating German prisoners of war.

Rowland Bevan Jones (far left) at his graduation ceremony in Leeds, 1943.

It was while working here that he met his future wife, Joyce Patricia Sillers (b. 17 March 1920, Leeds, Yorkshire – d. 12 September 2016, Noble’s Hospital, Strang, Isle of Man), a twenty-year-old nurse and local councillor’s daughter who had been raised mostly on the Isle of Man with her mother’s family. They were engaged in 1943 and married on 17 April the following year. By this time though preparations were already being made for the D-Day Landings, and Rowland, no longer a student, was enlisted as a lieutenant (later promoted to captain) in the Royal Army Medical Corps, the same regiment in which his uncle George had served during the first war. Rowland and Joyce spent their three-day-honeymoon at Harewood House near Leeds before Rowland was sent to Bradford in June for training, then on to Chilwell tank depot in Nottingham.

He landed in Calais shortly after D-Day before proceeding to Douai, treating injured troops coming back from the front. On 17 September 1944 the British launched Operation Market Garden, an attempt to push into Germany from the Netherlands. In order to do this a number of strategic bridges across the Maas and Rhine needed to be captured in order to stop the Germans from blowing them up. One of these was at Nijmegen near the German border, and it is here where Rowland was posted at the time of the offensive. He would have been under the command of XXX Corps, possibly in the Guards Armoured Division, and based at the 8th Guards Field Dressing Station.

The Germans resisted fiercely throughout September but by 20 September the Allies had captured the bridge, which had been due for demolition, and established positions on the northern bank. Operation Market Garden itself however was largely unsuccessful as the allies failed to cross the Rhine in sufficient numbers. The Nijmegen area was part of a small corridor of land captured by the Allies which over the following weeks would be expanded and eventually used a springboard for the renewed attack on Arnhem, a key Dutch city that had resisted capture during the operation.

Rowland was assigned to the Medical Incident Room at Arnhem after it was liberated by Canadian forces between the 12 and 16 April 1945. When the Germans surrendered on 8 May he was then posted to Germany where he served for two more years before being demobed in 1947. After returning home he moved in with Joyce and her mother Dorothy Maria Sillers at Lheany Road, Ramsey, on the Isle of Man, and then to their new house Claremont. Here he set up as a general practitioner with his colleague Bill Robertson, whose family lived with the Joneses at Claremont for a while. By this time Rowland and Joyce had had their first child, who would be joined by three more in the years to come.

Rowland’s father Arthur had retired in 1946, and he and Agnes had planned to move in with their son’s family at Claremont. Agnes however died quite suddenly in 1949 before the move took place and only Arthur ended up moving to Ramsey in 1950. She was sixty nine, and was described by their friend W.T. Tilsley as “a lovely lady, an ideal wife for a Methodist minister”. William Arthur spent ten years in Ramsey where, according to his obituary, “he exercised a quiet and efficient influence upon his son’s family and in the north of the island”:

All through his ministry he was characterised by earnest pastoral work for he was gracious with the children, diligent in sick-visiting, kindly to youth, and helpful to the unfortunate.

He died on 21 August 1960 in Noble’s Hospital in Douglas and was later cremated in Liverpool, the city where he had spent much of his childhood.

* * *

Arthur’s daughter Evelyn later moved to New Zealand with her husband George (who was by then a judge and industrial tribunal chairman), following two of her children who had emigrated there several years earlier. She died in 1993 aged eighty four. Rowland continued to practice as a G.P in Ramsey, during which time (according to his obituary) “he introduced new techniques and undertook an onerous on call commitment. He did GP obstetrics and looked after patients with tuberculosis at a time when there was neither an obstetrician nor a chest physician on the island.” He retired in 1985 and died on 8 May 2000 after several years of ill-health leaving behind four children and nine grandchildren.

In the next series of posts, Rowlands of my father, I will explore the ancestry of my grandfather’s mother Agnes, which will take us deep into the South Wales coalfield. Like her husband’s, her family story is defined in part by tragedy and scandal, but also an industrial legacy which would forever alter the physical and social landscape of an entire community.

Sources

Green, Geoff. “Revival on the Wirral”. Liverpoolrevival.org.uk. Merseyside Revival Trust. Accessed 26 July 2022. https://www.liverpoolrevival.org.uk/other-revivals/revival-on-the-wirral.

Roddy, Sarah, Julie-Marie Strange and Bertrand Taithe. The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, 1870–1912. Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.