This is the second in a series of posts on the history or the Rowland family of the Rhondda Valley. This part focuses on the children of Moses Rowland the Elder (1790-1837), including my fourth great-grandfather Morgan (1816-1884). For their story so far, see Rowlands of my father (part 1). Much of the information below has been pieced together through the combined efforts of multiple researchers over several years. In particular I would like to thank Philip Richards and Peter J. Williams for their invaluable help in researching these early generations. For consistency Welsh place names have been standardised to conform to their familiar modern spellings, and I have used the original ‘Rowland’ family name rather than the Anglicised ‘Rowlands’ variant which only became dominant towards the end of the nineteenth century.

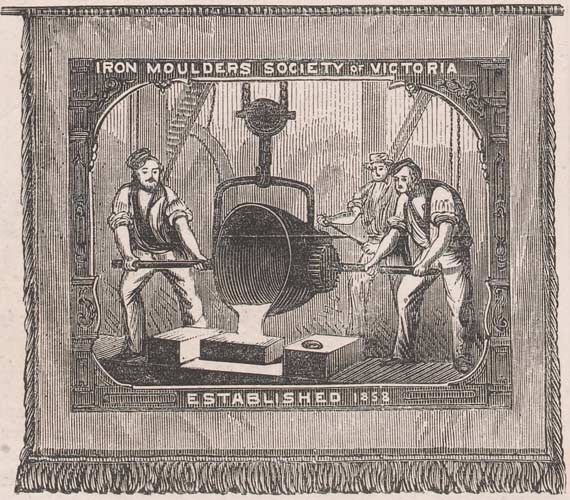

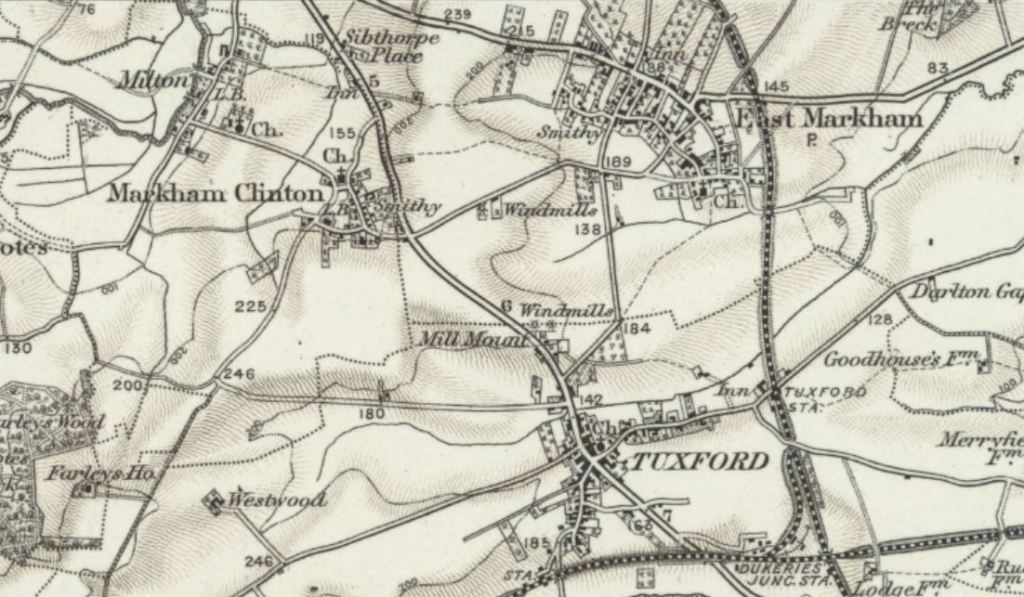

Morgan Rowland (b. c. 1816, Penderyn, Breconshire), the eldest of Moses Rowland’s seven surviving children, was working as a blacksmith around the time of his father’s death in 1837. This is confirmed in the Llantrisant parish registers, where his marriage to a young woman named Mary Foster (b. c. March 1818, Llantwit Fardre, Glamorgan) was recorded on 23 June 1838. They were twenty-two and twenty respectively, and living at Dinas Colliery at the time. Notably, despite Morgan’s father having been a teacher, both Morgan and Mary seem to have been illiterate, with each leaving an ‘x’ instead of signatures in the marriage register. Also somewhat curiously given Moses’s work as a Nonconformist lay preacher, the wedding took place in an Anglican church, but this was likely because a Methodist chapel had yet to established in the area. Mary was the daughter of a labourer and collier named Evan Foster (b. c. July 1778, Pentyrch, Glamorgan – d. c. November 1854, Cardiff, Glamorgan) and his wife Catherine (b. c. 1781, Glamorgan – d. c. November 1846, Cardiff, Glamorgan), who had moved to Dinas in around 1820. She was the seventh of eight siblings, whose names were:

- Evan (b. c. 1806, Llantrisant, Glamorgan – d. 6 June 1869, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Catherine (b. c. 1806, Llantrisant, Glamorgan)

- William (b. c. 1811, Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan)

- Daniel John (b. c. 1815, Llantwit Fadre, Glamorgan – d. c. November 1882, Pontdarwe, Breconshire)

- Hannah (b. c. 1816, Glamorgan)

- Morgan (b. c. 1816, Llantrisant, Glamorgan – d. 1868)

- Thomas (b. c. 1821, Dinas, Glamorgan)

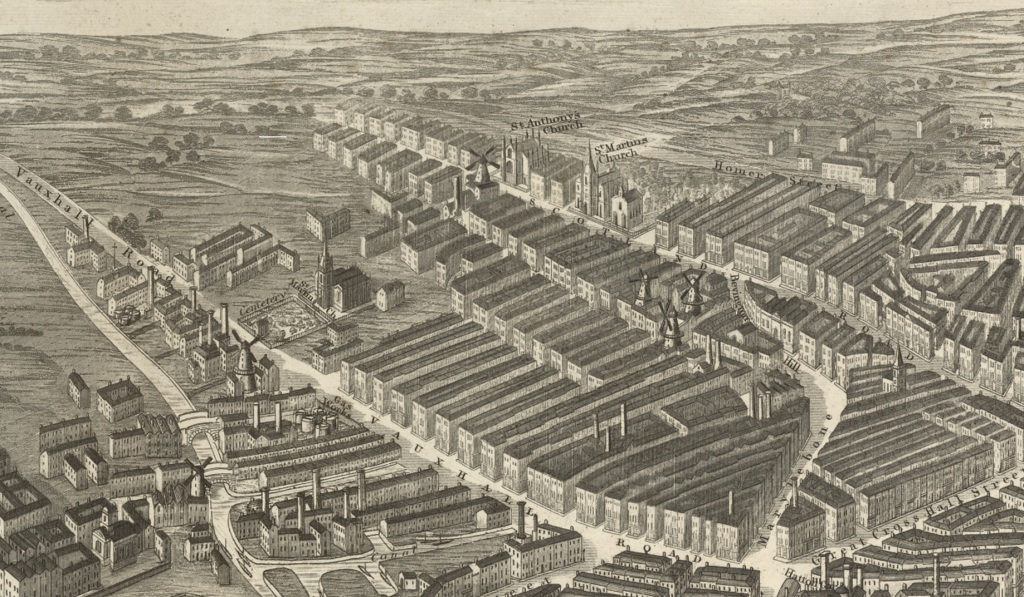

After marrying, Morgan and Mary appear to have remained in Dinas, where they were recorded in the 1841 census with their first child, a two-year-old daughter named Esther (b. 7 August 1839, Dinas, Glamorgan). At this time most of Morgan’s younger siblings, including his brothers Rowland (b. c. January 1821, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 19 March 1894 , Pontypridd, Glamorgan), Thomas (b. c. 1823, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 7 April 1888, Pontypridd, Glamorgan), and Moses (hereafter referred to as ‘Moses the Younger’ to distinguish him from his father, b. c. September 1828, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 21 September 1884, Penpisgah House, Penygraig, Glamorgan), plus his sister Anne (b. c. 1830, Llantrisant, Glamorgan), were still living with their widowed mother Mary in what is described as a ‘storehouse’ nearby.

This modest family dwelling was literally the storehouse of a local mill, where miners’ families were sometimes housed upon moving to Dinas before proper accommodation became available. Their residence here suggests that despite Moses’s status as the local schoolmaster, his wife and children were far from well-off. This is reflected in the humble occupations held by the three brothers still living at home: Rowland was a collier, presumably working for the local coal magnate Walter Coffin, and both Thomas and Moses the Younger were blacksmiths like Morgan. Anne, aged eleven, was neither working nor in school. As for Morgan’s other two sisters, Esther (b. c. January 1824, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 3 August 1895, Newton Nottage, Glamorgan) and Mary (Mary (b. 30 October 1825, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 14 April 1881, Penygraig, Glamorgan), Esther was recorded in the same census working as a servant in nearby Llanwono, while Mary’s whereabouts in 1841 are unknown. Their mother Mary Rowland (née Foster) passed away around November 1845 at the age of fifty, while some of the children were still in their teens. Following her death, her youngest son Moses the Younger, to whom we will return later, appears to have assumed the role of head of the Rowland household.

Morgan continued working as a blacksmith in Dinas for the next decade or so, perhaps principally engaged in making and repairing horseshoes for the local pit ponies. During this time he and Mary had five more children together:

- Moses M. (b. 19 February 1842, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 12 March 1901, Thornhill House, Treforest, Glamorgan)

- Elizabeth Foster (b. c. May 1845, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Evan (b. c. 1847, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Catherine (b. c. 1851, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. c. August 1920, Penrhiwceiber, Glamorgan)

- Morgan (b. August 1853, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. c. February 1915, Bridgend, Glamorgan)

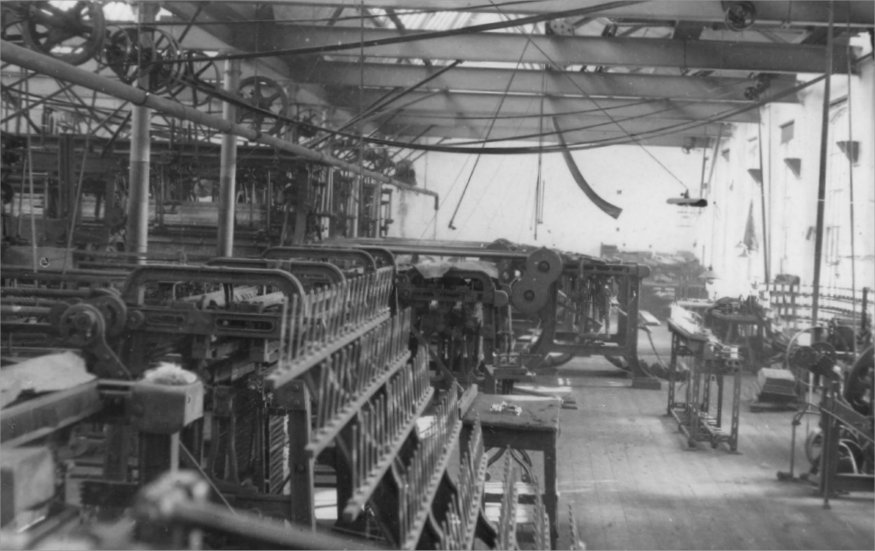

At some point between 1851 and 1853 however he left blacksmithing and began working for George Insole & Son at Cymmer Colliery in nearby Porth, first as a collier and then as a ‘fireman’ in 1854. Colliery firemen were among the first safety officers to be employed in mines, and were responsible for testing for flammable gases like methane and monitoring ventilation and air supply. This was especially important in the days when safety lamps were not yet widespread in South Wales, and most mines still relied on candlelight (Lewis, 1959, p. 62). Despite the increased status and responsibilities, working conditions for firemen like Morgan would have been just as dangerous as they were for the average mineworker, if not more so. Not only were they required to be the first down the mine before each shift to check for gas leaks or other potential hazards, they were also responsible for leading rescue and firefighting missions in the event of an emergency.

Until 1854, the fireman at Cymmer Colliery had been elected by the miners themselves (North Wales Chronicle, 23 August 1856), but this practice had been banned following a strike that year. Morgan was one of the first firemen to be appointed by the management. While the exact circumstances of how this came about are unknown, it seems plausible that Walter Coffin’s fondness for his late father Moses, former clerk at Dinas Colliery, may have been a factor (see Rowlands of my father (part 1). It is easy to imagine Coffin putting in a good work for him to James Harvey Insole at Cymmer Colliery, and the fact that Morgan’s younger brother Rowland was also promoted to overman here around the same time seems to support this theory.

The fact that family connections appear to have played a role in the appointment of key officers was unfortunately part of a wider pattern of mismanagement at Cymmer Colliery, and in the Rhondda Valley more generally. Coal output was prioritised above all other considerations, especially following Britain’s intervention in the Crimean War, with the most basic safety precautions only ever implemented following major disasters. Firemen and overmen like Morgan and Rowland were reportedly “too few in number to inspect the working places regularly and to instruct the colliers, many of whom lacked previous experience of coal mining, while some of the most vital safety points – for instance, the ventilation of doors – were in the sole control of young children” (Lewis, 1959, p. 149). In 1854 H.M. Inspector Herbert Mackworth delivered a list of special recommendations to the Cymmer Colliery’s owner James Harvey Insole. These included the appointment of a qualified mining engineer, the use of artificial ventilation, replacing naked light with locked safety lamps, and daily safety inspections. Every recommendation was ignored.

James Harvey Insole, c. 1870s. Source (via Wikimedia Commons).

On the morning of 15 July 1856, a massive explosion ripped through the Old Pit mine of Cymmer Colliery, killing a hundred and fourteen men and boys and injuring dozens more. Apart from one collier who died of burns from the initial blast, the majority were poisoned by methane or suffocated to death. It was the worst mining disaster ever recorded in terms of sheer loss of life, but it also devastated the entire local community by depriving it of virtually all its primary breadwinners. There was barely a household unaffected, with many losing both fathers and sons. In his Report for the South Wales District (1856, p. 127) Herbert Mackworth laid the blame squarely on “the persons in charge of the pit neglecting the commonest precautions for the safety of the men and the safe working of the colliery”.

At the subsequent inquest, Morgan was called for questioning along with the other firemen who had been on duty that day. The coroner, noting that all of them had apparently gone home by the time of the explosion, drew attention to a rule which stated that “the overman and his deputies shall maintain, during all working hours, a careful supervision of the air-way, working faces, and travelling roads and over all things connected with the ventilation, lighting, timbering, and the general or special safety of the workmen.” To this Morgan replied “I do not think that the rule requires the constant presence in the pit of the firemen” and went on to defend his record and that of his fellow fireman, who he claimed had followed all the established procedures on the morning of the explosion. Gas had, he admitted, been found in one of the stalls, but this had been indicated through the customary use of crossed timbers to prevent the miners going in there. Despite his protestations, there was understandably much anger towards towards Morgan, his brother Rowland the overman, and the rest of the management among the surviving workers, with one miner declaring he “would never work in the old pit so long as the Rowlands were there” (North Wales Chronicle, 23 August 1856).

At the conclusion of the case Morgan was found guilty of manslaughter through negligence by a jury of seventeen to one, along with his brother Rowland, the colliery manager Jabez Thomas, and the two other fireman on duty that day, David Jones and William Thomas (The Morning Chronicle, 23 August 1856). The following year on 24 February 1857, Morgan, Rowland and Jabez Thomas were tried again in Swansea for the willful murder of William Thomas, Samuel Edmonds and one other miner who died in the explosion, but this time the judge ordered Rowland’s acquittal, and after a favourable summing up the jury found Morgan not guilty (The Morning Chronicle, 4 March 1857).

It is unknown what Morgan did in the immediate aftermath of his acquittal, but by 1861 he was no longer employed as a fireman. On the night of the census that year he was recorded as a travelling coal agent lodging in a house in Bedwellty, Monmouthshire, while his wife and children were living at ‘Tai’r Prenafalan (Apple Tree)’, possibly a public house, in the hamlet of Castellau. The census also shows they had two further children after 1853:

- Rees David (b. c. November 1856, Llanwonno, Glamorgan – 2 April 1930, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Mary Ann (b. c. May 1860, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. c. May 1926, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

While the degree to which Morgan can or should be considered responsible for the Cymmer Colliery Disaster is debatable, survivor’s guilt and the part he played in the tragedy would doubtless have haunted him for the rest of his life. And while the likes of Morgan and especially the victims’ families would all suffer in their own ways for decades to come, it is notable that the one man with the power to implement better safety measures in the colliery he owned and ensure they were carried out, James Harvey Insole, was never brought to justice or even charged. He died an extremely wealthy landowner in 1901, two days before Queen Victoria.

* * *

We will return to Morgan Rowland and his family after looking at what happened to his siblings during this same period, whose lives were all very much intertwined. As previously mentioned, following the death of Moses the Elder’s widow Mary in 1845, their fifth son Moses the Younger became head of the Rowland household. The 1851 census records him living at Graig Ddu Cottages south of Dinas with his siblings Rowland and Anne, an eight year old nephew with the somewhat unoriginal name Moses Rowland Rowland, and interestingly a ‘grandmother’ called Elizabeth Rhys (b. c. 1766, Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan), a blind pauper and dressmaker who was perhaps his maternal grandmother. That year both Moses and his brother Rowland were employed as colliers, but shortly afterwards he qualified as a mechanical engineer. And then he made a discovery.

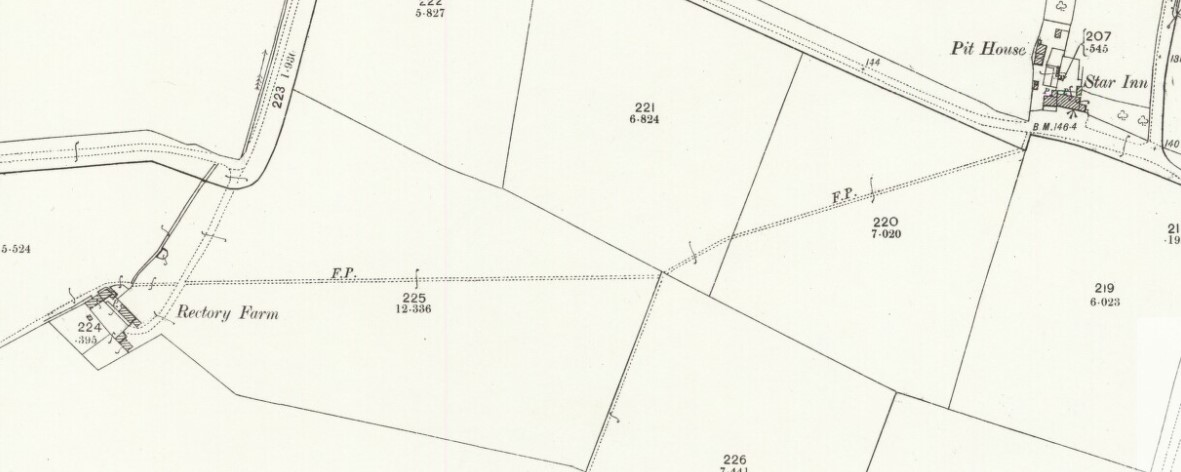

In 1858, on a piece of farmland near Dinas, Moses uncovered a coal seam with the help of a geologist named Richard Jenkins. That year at the age of thirty he founded the Penygraig Coal Company with a local builder named William Morgan, who was his brother-in-law through his sister Esther, a clerk named William Williams, and a jeweller called John Crockett (Egan, 1987, p. 36). In 1864 they sank the Penygraig Colliery, and the village which later grew up around it was named Penygraig after this original pit.

The business proved extremely profitable, with annual coal production reaching almost 100,000 tonnes by 1870 (Lewis, 1959, p. 73). In 1875 however, following a disagreement with his partner William Williams over where to sink the next pit he disbanded the Penygraig Colliery Company and founded the Naval Colliery Company with his brother-in-law William Morgan, and they sank the Pandy Pit (or Naval Steam Colliery) that year. Along the way he married a woman named Sarah Isaac (b. 6 November 1831, Eglwysilan, Glamorgan – d. 10 February 1912, Pontypridd, Glamorgan), with whom he had at least three children:

- Emily Mary (b. c. 1859, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Sarah Ellen (b. c. 1862, Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan)

- Moses (b. c. 1864, Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan)

They lived together first at Mount Pleasant in Ystradyfodwg, then at Penpisgah House in Penygraig. By the time he died on 21 September 1884 aged only fixty-six he had amassed a personal fortune of £21’609 12s 8d (worth around £2,218,463 today). However, as will be shown, his business was beset by financial difficulties, and in the final years of his life two tragedies within a short space of time would take a serious toll on his mental health.

While the sinking of the Penygraig Colliery and Moses’s subsequent business ventures would undoubtedly have a deep and lasting influence on the Rhondda Valley, their most direct impact was on his siblings. His eldest sister Esther had married Moses’s junior business partner William Morgan on 30 April 1842. Originally a stone mason by trade, William was working as a builder by the time he and Moses went into business, and he later became a successful coal exporter. During their forty-three year marriage he and Esther had at least the following seven children together:

- Emily (b. 14 March 1843, Pontypridd, Glamorgan – d. 4 October 1867)

- Moses (b. 20 October 1844, Pontypridd, Glamorgan – d. 18 April 1885, Cardiff, Glamorgan)

- John (b. 27 August 1846, Llanwonno, Glamorgan – d. 5 July 1919, Cardiff, Glamorgan)

- Mary (b. 10 April 1848, Pontypridd, Glamorgan – d. 8 December 1855, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Thomas (b. 13 April 1850, Pontypridd, Glamorgan – d. 13 April 1850, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Daniel (b. 16 February 1851, Pontypridd, Glamorgan – d. 5 May 1855, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Charles (b. 3 June 1854, Llanwonno, Glamorgan – d. 29 June 1932 Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

After a period of ill-health William died on Christmas Eve 1885. Esther passed away a decade later on 3 August 1895, at which time her personal estate was worth £4,675 0s 2d. She was buried at Pontypridd five days later.

Moses’s other older sister Mary, on the other hand, seems to be his only sibling who did not benefit in any obvious way from her brother’s success. On 6 November 1847, at the age of twenty-two she had married a blacksmith called John Martin (b. c. 1823, Bridgend, Glamorgan – d. c. 1908, Pontypridd, Glamorgan), possibly a workmate of her brothers, with whom she had at least seven children:

- Francis (b. c. 1847, Llantrisant, Glamorgan)

- Anne (b. 11 June 1848, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Mary Jane (b. c. 1851, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- David (b. c. 1854, Llantrisant, Glamorgan)

- Elizabeth (b. c. 1857, Llantrisant, Glamorgan)

- Esther (b. c. 1860, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Margaret (b. c. 1863 Dinas, Glamorgan)

The family remained in the Dinas-Penygraig area all their life, and Mary died on 14 April 1881 aged fifty-five. Unlike Mary, Moses’s younger sister Anne did appear to benefit from her brother’s success, albeit indirectly through her husband William Thomas (b. c. 1832, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire). William was recorded as a coal miner in the 1861 census, when he and Anne were living in his hometown of Llanelli, Carmarthenshire. By 1871 however they had moved back to Penygraig, and William was working as a foreman coal tipper. Given the timing it seems plausible this promotion was enabled by his brother-in-law Moses, whose mining operation was well-established by this point. After 1871 it is unclear what became of either him or Anne, but they are known to have had at least two children together:

- Mary Ann (b. c. 1857, Cymmer, Glamorgan)

- Elizabeth (b. c. 1863, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire)

Like her husband, Anne’s older brother Thomas also worked as a foreman at Penygraig Colliery for a time, another beneficiary of Moses the Younger’s nepotism perhaps. Since the age of at least eighteen he had been employed as a blacksmith like his brothers Morgan and Moses, and in around 1843 had married Mary Isaac (b. c. 1825, Dinas, Glamorgan) in Cardiff, with whom he had two children:

- David (b. c. 1848, Dinas, Glamorgan)

- Mary Ann (b. c. 1851, Porth Glamorgan)

Shortly before the birth of their second child, Thomas and his family had moved to Porth, where his brothers Morgan and Rowland would soon take up positions at Cymmer Colliery. The 1851 census shows them living in a cottage with two lodgers (both coal miners), but sadly Thomas’s wife Mary passed away later that same year. He remarried about four years later to another woman, also called Mary (surname unknown, b. c. 1818, Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan – d. 22 August 1886, Llantrisant, Glamorgan), with whom he had at least one more child:

- John (b. c. 1857, Porth Glamorgan)

By 1861 they had moved again to Castellau, near where Thomas’s brother Morgan was living at the time. Their address was recorded as the Colliers Arms, which they appear to have been running as a lodging house with five guests staying with them on the night of the census. This was evidently a profitable sideline, as although Thomas was still working as a blacksmith the family were earning enough by then to employ a domestic servant.

This was still the case in 1871, by which time Thomas had been hired as a colliery foreman, presumably by his brother Moses at Penygraig, and his eldest son David had started working as a grocer. Interestingly, their address that year is given as ‘Penygraig Store Dinas’, quite possibly the same storehouse where the Rowlands were recorded living as far back as 1841. Thomas’s stint at his brother’s company was to be short-lived however, as by 1881 he had changed careers yet again and was working as a butcher alongside his son at 12-13 Penygraig Road, Ystradyfodwg. His wife Mary died on 22 August 1886, and Thomas himself passed away at the age of sixty-five on 7 April 1888. He was buried at Cymmer Independant Chapel.

Like Thomas, Moses’s other older brother, Rowland, would also become involved in the family’s colliery business. Of all his siblings, he is perhaps the most intriguing figure. In his youth, he lived at Dinas Storehouse with his mother and several of his brothers and sisters. At the time of his first marriage to Susannah Jones around 1842, he was working as a collier. Unfortunately, not much is known about Susannah except that she and Rowland had a son together, Moses Rowland Rowland (b. c. August 1943, Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 24 Mar 1926, Bridgend, Glamorgan), and she likely passed away before 1851. In the census for that year, Rowland and his son were recorded living with his brother, Moses the Younger, at Graig Ddu Cottages. Curiously however, he listed his marital status as ‘unmarried’ rather than ‘widowed’. This could have been a simple error or the couple could have separated and were living apart by this time. Later, he married for the second time to a woman named Ann Williams (b. c. 1826, Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan – d. c. November 1871, Pontypridd, Glamorgan).

Rowland’s employment as a foreman at Cymmer Colliery and his subsequent trial, conviction, and eventual acquittal following the disaster of 1856 have already been discussed in relation to Morgan. After this major setback, however, like Morgan, he became a coal agent (traveling salesman). The 1861 census shows him living at ‘Ty Rowlands’ (Rowland House) in Llangendeirne, Carmarthenshire, with his wife and seventeen-year-old son, who had become an accountant, perhaps while on an extended business trip. A decade later, at the age of fifty, he was living at Bryncelyn, near Ystradyfodwg, where he was apparently prospecting for coal in the Garw Valley while also working as a colliery manager for his brother Moses at Penygraig (Morgan, c. 1975). Living with him that year were his wife Anne, his mother-in-law Jane Williams, two lodgers, and a twenty-seven-year-old domestic servant named Jane Davies (b. c. 1843, Pontyates, Carmarthenshire – d. 6 May 1914, Pontypridd, Glamorgan).

In the 1881 census, Jane was recorded living with Rowland again at 60 Trafalgar Terrace, Ystradyfodwg, however not as his servant but as his third wife. Sadly, Rowland’s second wife Anne appears to have died in late 1871, but Rowland is alleged to have divorced her before she passed in order to marry Jane, which he did in around May 1872. He and Jane had three children together, the youngest of whom would go on to serve as a Member of Parliament for Flintshire:

- Esther Mary (b. c. 1876 Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan – d. c. February 1919, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Rowland (b. c. 1878 Ystradyfodwg, Glamorgan – d. 14 January 1904, Pontypridd, Glamorgan)

- Gwilym (b. 2 December 1878 Dinas, Glamorgan – d. 16 January 1949, Penygraig, Glamorgan)

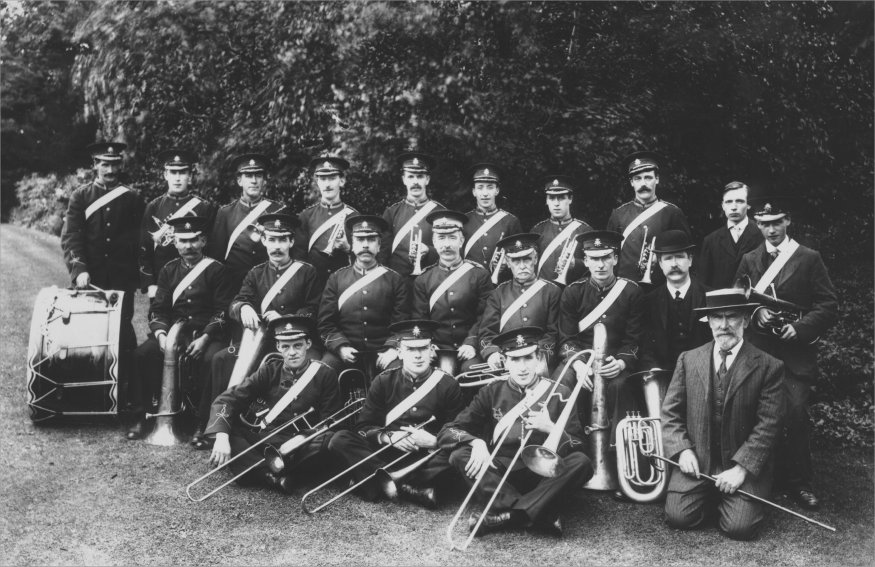

Despite his questionable personal life, Rowland was widely respected in the Rhondda Valley as a thoughtful theologian, a passionate advocate for the temperance movement, and an eloquent speaker. He served as a member of the Penygraig School Board and was a deacon with the Calvinistic Methodists at Dinas, then later at Pisgah Calvinistic Methodist Chapel, where he was appointed treasurer in 1868 (Morgan, c. 1975). He was also apparently held in high esteem by his workers, who, in an illuminated address from 1873, described him in rather florid prose as “a celebrated manager, the generous Rowlands [sic]; the abstainer’s leader, from whose zeal Penygraig is like a peaceful paradise … our unrivaled hero through whose work the “strike” is finally banished from cheerful Penygraig.”

Rowland retired sometime before 1891, by which time he was living at 9 Tylacelyn Road, Clydach, with his young family. He died three years later on 19 March 1894 at the age of seventy-three. According to his probate record, his final address was 36 Bryncelyn Road, Penygraig, and his effects worth £141 6s 3d went to his widow Jane, who herself passed away on 6 May 1914. Writing some years after his death, Dinas historian William James said of Rowland:

I have not knowingly come into contact with any working class man who was more sagacious than he. From what I knew of him I suspected he had too much spirit in him to stay on top of any matter for very long. If he could have confined himself to the matter in hand, it’s likely enough that he would have achieved his ambitions within many circles. Despite this, he moved in important situations during his life. He was a Sunday School teacher with but a few comparables in Dinas. He had a a particular attribute for gaining the attention and affection of his class, apart from being able to impart education to them. He did enormous good for many in Dinas with his efforts with abstinence; the results of his work in this direction will benefit generations to come. His family, by necessity feels a great loss with his death; his care for his children was so great; one can almost say that he was too extreme in this direction.

William James, 1902

* * *

We now return at last to Morgan, the eldest of the Rowland siblings and my great-great-great-grandfather. When we left him in 1861, he had been a travelling coal agent like his younger brother Rowland. Three of his children had already begun work by that time: his first child, and the only one to have left home so far, Esther, was employed as a servant in Llanwonno, his oldest son, Moses M., was an engineer, and Evan was a coal miner. These occupations reflect the fact that the Penygraig Colliery Company was still in its infancy at this stage, and the Rowland family were yet to benefit from it collectively.

By 1871 all of that had changed. Morgan was a manager at Dinas Colliery, and the family’s improved fortunes were evident from the fact that they were employing a domestic servant in their home at 1 Five Acres, Dinas. Of the children still living at home, Evan had risen to become a colliery overman, while Rees David was a shepherd, and Catherine was a milliner. The previous year, their eldest daughter Esther had married William Williams, a former clerk and her uncle Moses the Younger’s business partner in the Penygraig Coal Company. Williams was, by then, one of the company’s owners. Another of Morgan and Mary’s daughters, Elizabeth Foster Rowland, had married a mining engineer named William Lewis in 1869.

During his tenure as manager at Dinas, Morgan featured in a number of local news stories, which paint an interesting picture of his time there. One such story from 30 August 1871 recounts how he had apprehended a man he believed to be stealing some ‘tramroad plates’ (iron railway plates) from Dinas Colliery. The man then jumped up and grabbed Morgan by the beard, pulling out a tuft “the size of a small bird’s nest” (Western Mail, 31 August 1871), which he subsequently produced as evidence in the court case that followed. This was not the only time he appeared in court due to alleged cases of theft at the colliery. On 5 February 1875, Morgan accused an employee of stealing some sticks, however, he had already been annoyed with that particular worker because he was leaving the company. The defence argued that Morgan “always suspects people that he dislikes”, and the case was dismissed (Western Mail, 3 February 1875). Later that year, on 5 June, he featured in a report covering a robbery of 5d worth of oats from the colliery’s stables (Western Mail, 5 June 1875).

Morgan also featured in a number of more serious stories. On 26 April 1879, following a gas explosion at Dinas Colliery earlier that year, he became a key witness for the prosecution. By then, he was no longer working at Dinas Colliery, but he told the court that during his time there, he had repeatedly warned the owner about the negligence of an overman named Chubb, who had been promoted to colliery manager at the time of the explosion (Northern Echo, 28 April 1879). Perhaps his experiences after the Cymmer Colliery explosion had caused him to become especially safety conscious in the years since. An article from 14 October 1880 shows that he was present and aiding during the aftermath of a later mining disaster, but this time it was at the family firm, the Naval Colliery Company (The Glasgow Herald, 14 December 1880).”

On 10 December 1880, twenty-three years after the Cymmer Colliery Disaster, another horrific gas explosion killed one hundred and one miners at Penygraig. Once again, the Rowland family was implicated. Due to the family’s nepotistic hiring practices, one of Rowland Rowland’s sons, the former accountant Moses Rowland Rowland, had been appointed as a manager at the Naval Steam Colliery, despite lacking the necessary experience or qualifications. After the explosion, a Home Office Inquiry revealed that his only previous experience had been “as a clerk, storekeeper, and measurer, primarily involved in book work, and, as he expressly stated, not engaged in the practical duties of mine managing.” Moreover, his manager’s certificate “was entirely false…and the owners of the colliery, or some of them, must have known it to be false.”

No one was charged in the end, but the jury strongly condemned the company’s owner Moses the Younger for neglecting to follow a number of safety measures. A second explosion on 27 January 1884, which killed another fourteen men, further tarnished the Naval Colliery Company’s reputation and brought yet more suffering to an already traumatized community. Moses was said to have experienced severe anguish at the loss of life in the two explosions, and in his final months began to manifest “symptoms of mental disturbance” (Western Mail, 23 September 1884). The company also suffered as a result of the Long Depression in the 1880s, and it was eventually sold off in October 1887, less than thirty years after Moses discovered the original coal seam at Penygraig.

* * *

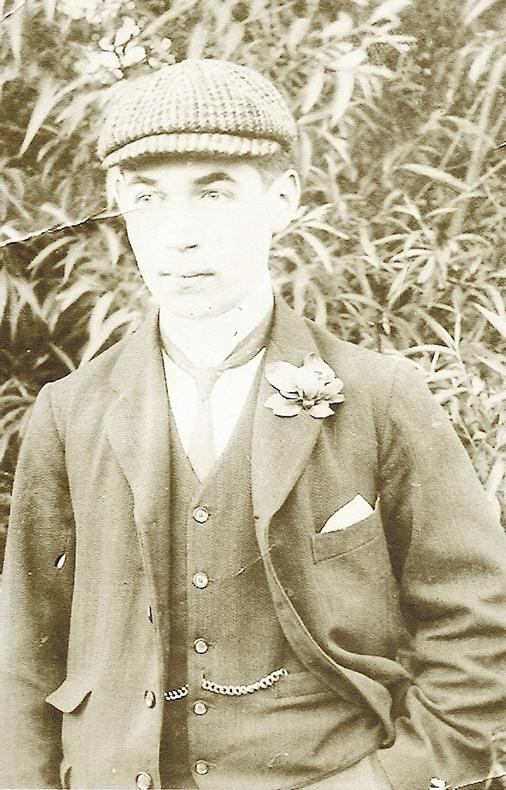

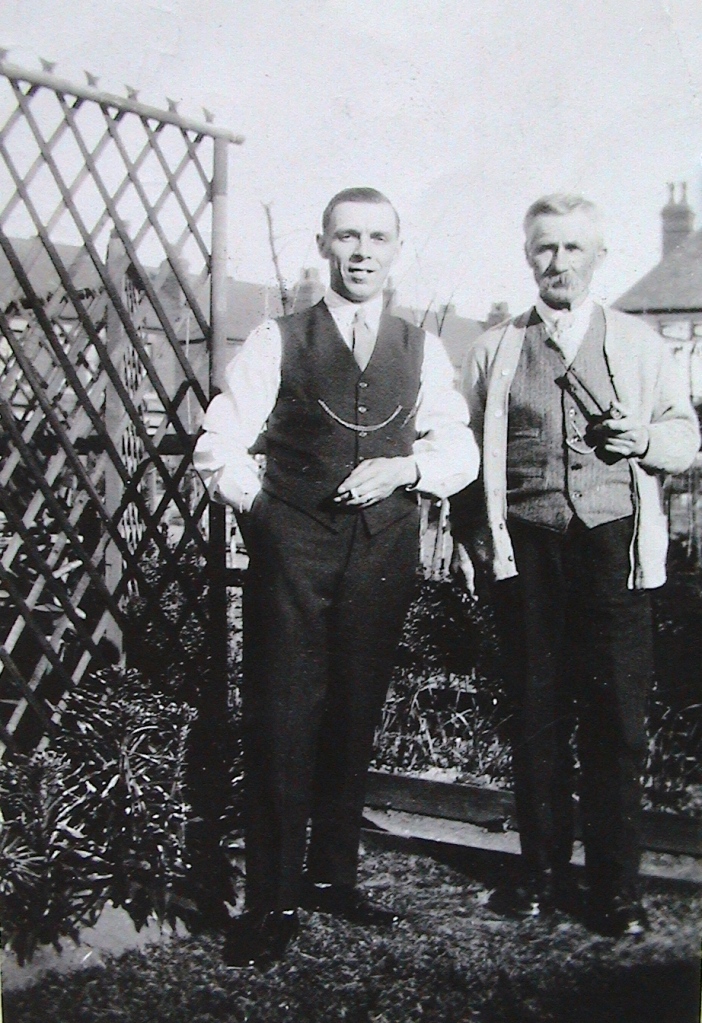

By the early 1880s Morgan and Mary were living at Grovefield Terrace, Dinas, with their daughter Mary Ann and a domestic servant. Mary passed away on 6 June 1883 aged sixty-five, and Morgan died the following year of ‘morbis cordis ascites’ (possibly caused by cancer) at the age of sixty-eight, uncannily on the exact same day as his brother Moses the Younger, 21 September 1884. Given the timing, it is impossible to ignore the possibility that the second Naval Colliery disaster may have hastened their declining health. Morgan’s eldest son, my great-great-grandfather Moses M. Rowland was present at his death. He was buried in Ebenezer Chapel on 22 September, and his personal estate at the time was worth £318 14s. In his obituary he was described as “a remarkable man”, “one of the best colliery managers”, and “remarkable in the neighbourhood for his attachment to intellectual pursuits” (Western Mail, 23 September 1884). His only known photograph is a faded studio portrait of him sat with his younger brother Moses, taken a few years before they died within hours of each other.

The deaths of the two great Rowland patriarchs in 1884 marked the end of an era, not just for the family, but for the Rhondda Valley as a whole. Starting from virtually nothing, by the early 1880s the Rowlands had become a kind of local industrial aristocracy. Their reliance on family connections over merit when appointing staff would ultimately prove disastrous, but their closeness as a family had also undoubtedly been key to their early success. Although the Rowland, or increasingly ‘Rowlands’, name would continue to carry some weight, Morgan’s children, including my great-great-grandfather, would never experience the same wealth and influence as their parents. In the next post, we will look at the lives they led in the aftermath of the previous generation’s spectacular rise and fall.

Sources

Egan, David. Coal Society: A History of the South Wales Mining Valleys. Gomer, 1987.

James, William. Hanes Dechreu yr Achos Crefyddol yn Ninas y Rhondda: Ynghyd a Sylwadau ar Nodweddion Amryw Bersonau. Tonypandy: Argraffwyd gan Robert Davies, Maddock, a’u Cyf. 1902. Translated by Philip Richards, 2007.

Lewis, E.D. The Rhondda Valleys: A Study in Industrial Development, 1800 to the Present Day. London: Phoenix House, 1959.

Morgan, Tudor Reynolds. The Rowlands Family, Penygraig, Rhondda Valley. c. 1975.

Northern Mine Research Society. “Cymer Colliery Explosion, Rhondda Valley, 1856”. Accessed 18 September 2023. https://www.nmrs.org.uk/mines-map/accidents-disasters/glamorganshire/cymer-colliery-explosion-rhondda-valley-1856/.

Northern Mine Research Society. “Pen-Y-Craig Colliery Explosion, Rhondda, 1880”. Accessed 20 December 2023. https://www.nmrs.org.uk/mines-map/accidents-disasters/glamorganshire/pen-y-craig-colliery-explosion-rhondda-1880/.