This is the second in a series of posts on the Hall family, the maternal ancestors of my great-grandmother Maud Ling (my maternal grandfather Frederick England’s mother), the first of which can be found here. This part will focus primarily on Maud’s grandparents Miriam Hall and Charles Buxton.

* * *

Miriam Hall was born in Lambley, Nottinghamshire in 1833. Her baptism record from 30 June that year gives her parents’ names as John and Ann Hall, however as was mentioned in the previous post, unlike her brothers, John Jr., Thomas and William, she was not present at their house on the night of the 1841 census. It’s possible her name was simply missed off the schedule, or she may have been staying with relatives, but whatever the reason her whereabouts that year remain unknown. Her earliest confirmed appearance in the census would not come till 1851, by which time she was eighteen and living with her parents in Alfreton, Derbyshire.

One fact which the census did not record however, and which was perhaps unknown even to Miriam at this point, was that by then she would have been about four weeks pregnant. On 29 November 1851, almost eight months to the day after census night, Miriam gave birth to a little girl named Mary Ann. Unsurprisingly for a child born outside marriage in the 1850s, no father was mentioned by name on either her birth certificate or her baptism record from 4 January the following year.

As has been shown in earlier posts regarding George and Susannah Ling, Nineteenth Century attitudes towards illegitimate children and their mothers were often unswervingly condemnatory. We of course don’t know how sympathetic Miriam’s family were to her situation, but we do know that five years after her daughter’s birth she was living in Carlton, Nottinghamshire, only three miles from where she had been born in Lambley. Perhaps once the signs of her pregnancy began to show it was decided, mutually or otherwise, that it would be better for Miriam to stay with relatives for a few years to avoid a scandal?

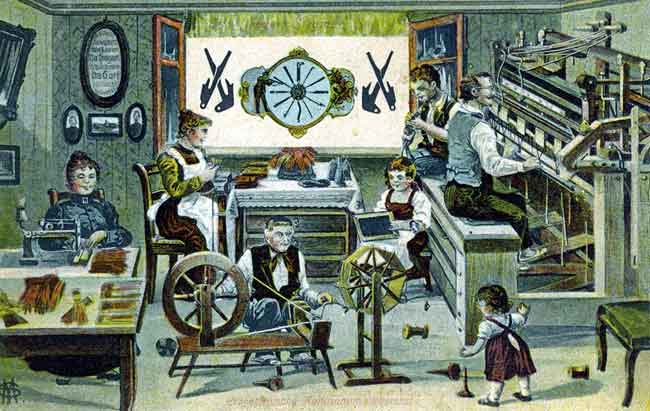

Ironically, the only reason we know about Miriam’s move to Carlton is because by 1856 she had become pregnant once again. We know this because on 24 September that year she gave birth to a son, William, exactly six months after her marriage to a man named Charles Buxton at All Hallows church in nearby Gedling. From their marriage certificate we can see that Miriam had been working as a dressmaker, and that, interestingly, her two witnesses were James and Harriet Burton, both first cousins by her maternal uncle Benjamin Burton. According to the 1861 census, Benjamin and his family were living in Carlton at around this time, so it seems likely he was the relative who took Miriam in following her first pregnancy five years earlier.

So what of Charles, the man she married? Their certificate states that he was a twenty nine year old tailor, the son of a ‘messenger’ (postman) named William Buxton, and that like Miriam he had been living in Carlton before the wedding. Further research into his past reveals that he had been born in Alfreton on 26 September 1826, and that by 1841 he was working as a servant in a house on Leeming Street in Mansfield. Shortly afterwards he must have secured an apprenticeship as by 1851 he was already working as a tailor back in Alfreton, just a few doors away from Miriam and her family. Given their proximity it’s not impossible that Charles was the father of Miriam’s first child, Mary Ann, who was born later that year. While only a DNA test could prove this definitively, a pre-existing relationship with Miriam would certainly explain Charles’s presence in Carlton in 1856.

Once they were married Charles and Miriam moved back to Alfreton, perhaps because their new status as husband and wife enabled them to pass off Mary Ann as legitimate. Here they went on to have seven children together over the next eleven years, whose names were:

- William (b. 24 September 1856, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- John Samuel (b. 8 July 1859, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- Emma Elizabeth (b. 15 February 1863, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. May 1895, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- Rose Ellen (b. 19 March 1867, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 28 August 1925, Ripley, Derbyshire)

- Frederick Charles (b. 11 March 1870, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 3 August 1937, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- George Henry (b. 14 April 1873, Alfreton, Derbyshire – 5 September 1953, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- Alfred (b. 2 March 1877, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 12 Jul 1946, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

As late as 1857 Charles was still working as a tailor (according to that year’s edition of White’s Directory), but was recorded as a postman in the 1861 census. Unlike his father William, who had started working for the Post Office on 9 1848, Charles’s name does not appear in the British Postal Service appointment books. This suggests he may have been employed on a fairly casual basis, perhaps helping out his sixty seven year old father with his daily rounds. William’s route according to the appointment books was between Alfreton and the nearby village of Pinxton so it seems likely Charles would have travelled this same way. Each day he would have set off from his home on Derby Road, picking up the mail from postmaster Thomas Tomlinson Cutler’s house on New Street before making his deliveries on foot or by horse and cart.

By 1870, according to his son Frederick’s baptism record, Charles had changed careers again and was working as an innkeeper at the Devonshire Arms on King Street. It’s not exactly clear how this came about, however his father’s will written the following year mentions a piece of land on Lincoln Street “now used as a garden and in the occupation of son Charles Buxton”, which is presumably a reference to the Devonshire Arms’s beer garden. Although Charles is the only member of the family explicitly mentioned as running the Devonshire Arms in the census returns, it is likely the whole family including Miriam would have helped out in one way or another, serving drinks, cooking meals or preparing guests’ rooms.

The need to provide meals for his guests in addition to drinks, accommodation and stabling may explain why from at least 1873 Charles also appears to have worked as a greengrocer, fruiterer and fishmonger. Inevitably ordering large quantities of food for the Devonshire Arms would have left him with a certain amount of surplus stock, and therefore a stall at Alfreton market place would have seemed like a profitable way of selling on some of it. Although clearly an enterprising man, a newspaper report from 1878 suggests he may not always have been overly fastidious in his work, as that year he was fined £1 and costs for having several incorrect weights on his stall on 25 January, despite his protestations that he had had them adjusted four times in the past year (The Derbyshire Times, 27 February 1878, p. 3, col. 4).

Charles also appears to have branched out into farming, as around this time he had been renting “a large field which runs parallel to the railway at [South] Wingfield” (The Derbyshire Times, 26 January 1876, p. 3, cols. 4-5). Charles was mentioned in the local newspaper when two of his horses from this field wandered onto the railway lines on 24 January 1876 and caused an enormous collision. They had apparently been able to reach the tracks due to two unlocked gates which separated Charles’s field from some waste ground used by the Midland Railway Company and the railway itself. Fortunately the horses were the only casualties, however there was a great deal of property damage, including to South Wingfield Station itself. According to The Derbyshire Times:

The shock of the concussion was such that many of the trucks were thrown into the six-foot, and one of them was lifted right onto the platform, where both it and its contents were so thickly strewn as to impede the free passage of the platform. This train was wholly loaded with beer and grains, and for some distance the line was covered with splintered waggons, ironwork twisted into the most fantastic shapes, and bulged-in beer casks.

Before the track could be cleared a “heavily-laden mineral train dashed up at a high rate of speed”:

The result can only be imagined. The engine dashed into those portions of the trucks which were fouling the down-line, and so violent was the impact that the engine was greatly damaged, and a large number of trucks were thrown off the line, which was strewn with coals. With the exception of twelve yards the whole of the platform at Wingfield station was torn up, the large coping being smashed like cardboard. The rails were torn up, and the sleepers wrenched from their positions, the line being completely wrecked.

Later that year Charles attempted to claim £45 in damages from the Company for the loss of the two animals (The Derbyshire Times, 24 June 1876, p. 3, col. 4). Several years later another news story described a strikingly similar incident, when Charles was charged with “allowing three cows and a calf to stray on the highway at South Wingfield, on August 31st” (The Derbyshire Times, 4 October 1893, p. 3, col. 7) after the villagers at Highfield “had complained about the cattle getting into their gardens and eating their vegetables.” Charles’s defence was that his field was overrun with people and he could not keep the gate shut, but in the end he was fined 12s. and costs.

By 1903 Charles, now seventy six, had been largely confined to his bed for several months due to general ill-health. After leaving his bed at around 4.30 pm on Thursday 19 March his shirt accidentally caught flame from the bedroom fireplace. Miriam, who had been preparing his tea, rushed upstairs after hearing his screams, but was too late to prevent his burns to the head, neck, arm and sides. He died the following evening on 20 March, and later a jury gave the cause of death as shock from the burns (The Derbyshire Times, 28 March 1903, p. 5, col. 4). In his will he left Miriam £123. Miriam herself died seven years later on 30 March 1910, also aged seventy six, and in her will she is said to have left behind the not inconsiderable sum of £985 17s. 1d., presumably the full value of The Devonshire Arms, which still stands on King Street today.

In the next and final installment of this series I will be be looking at the children of Miriam Hall and Charles Buxton, including my great-great-grandmother, Miriam’s illegitimate daughter Mary Ann Hall. In it we will see how her marriage to John Ling brought together two of the most prominent families in Alfreton, and how her influence profoundly shaped the lives of her descendants.