This is the third and (for now) last in a series of posts describing the paternal ancestry of my grandfather Frederick England, the first two of which can be found here and here. This part mainly focuses on his grandfather Thomas England’s children, including Frederick’s father Thomas England Jr. (1878-1944).

* * *

The funeral of Cllr. Thomas England at Swanwick Baptist Church on 24 February 1918 would have been one of the largest family gatherings the Englands had held for many years. The extensive list of mourners reported in The Derbyshire Courier (2 March 1918, p. 1, col. 5) gives some indication of the family’s size at this time, but also raises some puzzling questions. Among those present were his older brothers George and James, his older sister Mary and younger half-sisters Alice and Elizabeth, plus a fourth sister, ‘Mrs. Watson,’ who I have yet to identify. His two other known sisters, Hannah and Ann, had both died decades earlier, and while this Mrs. Watson could have been his half-brother William Grice’s widow Mary, I can find no proof that William died before 1918 nor that Mary later remarried and took the name ‘Watson.’ The identity of the second mystery mourner, ‘Mrs. T. England (widow),’ is even more obscure. Thomas’s wife Mary Ann had died in 1913 according to the same headstone beneath which Thomas was interred. This newspaper report is the only evidence I have ever found of him marrying for a second time between 1913 and 1918, and although it’s possible the they could have made a mistake I think this is unlikely given how detailed and comprehensive the rest of their account is. The idea of Thomas remarrying in his mid-sixties is perhaps surprising but at present I can think of no other explanation for this enigmatic widow’s presence at his graveside. Hopefully further research will reveal more in time.

Also present at the funeral were, of course, all of Thomas’s surviving children with the exception of one, to whom I will return later. His five daughters Lucy Ann, Emma Jane, Lottie, Nellie and Amy all attended with their husbands and families. The eldest, Lucy Ann, had married an electric crane driver from Northamptonshire named John George Smith with whom she’d had one daughter. John had died not long afterwards however, and by the time of her father’s funeral she was married to another man named Herbert Hoskin, a labourer at a chemical works. Thomas’s second daughter Emma Jane had at least six children with Frederick James Fido, and Lottie, who was recorded as a dressmaker’s assistant in the 1911 census, had married George Whylde in 1913. Both husbands were local coal miners. Lottie’s death at the age of ninety two in 1987 makes her the longest lived of Thomas’s children, as well as the only one whose life overlaps with my own. Nellie, unmarried at the time of the funeral, went on to marry a lorry driver named Walter Syson three years later but it is unknown whether or not she had any children. Thomas’s youngest daughter Amy had four boys and two girls with Bertie Crownshaw, a baker from Sheffield, but sadly, as is the case with the rest of Thomas’s daughters, not much else is known about her. The only son of Thomas’s named in the list of mourners is his third, John James England. According to one of his descendants, John had been a boot boy at the Royal Alfred Hotel in Alfreton when he was ten before securing an apprenticeship as a sawyer’s labourer. By 1911 he was working at a chemical works (possibly Kempson & Co. of Pye Bridge, his father’s company) and had married Bertha Ellen Sparham, with whom he had five children. He is remembered fondly as a very “quiet, gentle man.”

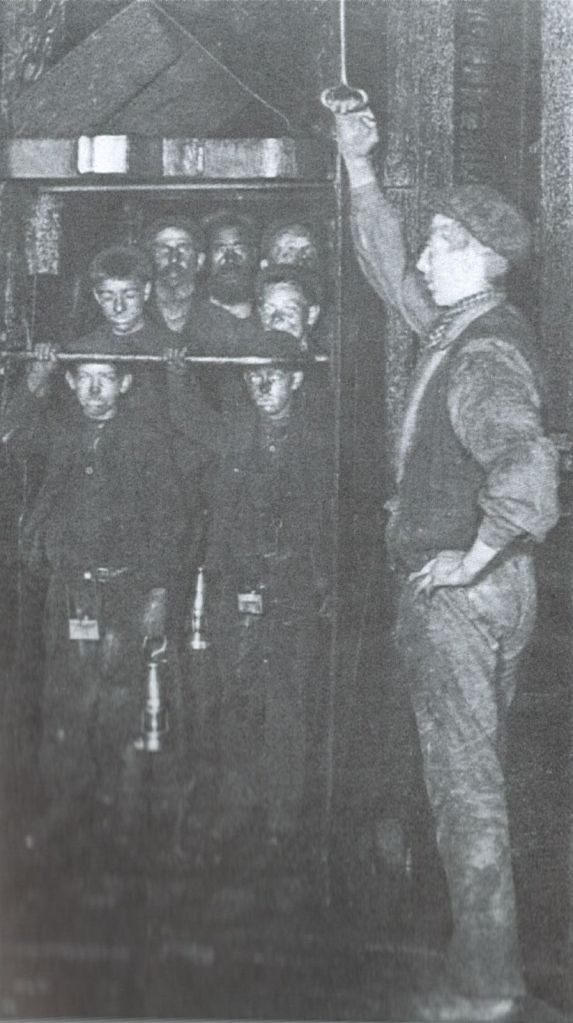

So where were Thomas’s other sons? His eldest George William England had, like his father, been a coal miner since he was a boy, and by his early twenties was working as a hewer, one of the most dangerous occupations in an industry comprised largely of dangerous occupations. Hewers were responsible for loosening rock at the coalface with picks, working deep underground in sweltering conditions. By the time George started working in the 1890s there were still no restrictions on the number of hours a miner could be obliged to work per day, wages could be cut arbitrarily and safety measures were still minimal. But while the average miner’s working conditions could be said to have improved little since George’s grandfather’s fatal accident in 1850, the organised labour movement had grown in strength by then and was starting to demand a better deal.

In 1893 when George was sixteen the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain called a strike against a proposed 25% pay cut, in which George’s union, the Derbyshire Miners’ Association (according to The Derbyshire Courier, 10 July 1915, p. 5, col. 4), were participants. The strikers held out for many weeks, and eyewitnesses at Swanwick Colliery recalled seeing pit ponies, which perhaps had not seen daylight for years, grazing freely above ground (Stone, 1998). Unlike earlier strikes in the area though this one was a success, and the management agreed not to reduce any wages. Industrial action by miners would of course continue throughout the twentieth century, including the National Coal Strike of 1912 which began in Alfreton and soon spread across the country. Their core demands were expressed in a popular chant, which could be heard at pits from Kent to Clydeside:

Eight hours work, Eight hours play,

Eight hours sleep and

Eight bob a day

The miners’ victory that year led to the passing of the Coal Mines (Minimum Wage) Act 1912, one of the first minimum wage laws passed anywhere in the world and a huge milestone in the history of workers’ rights. Many of the basic freedoms we enjoy at work today owe a great deal to the efforts of people like George, his brothers, their wives and workmates.

At the time of the strike George had been working at Birchwood Colliery in Alfreton for about seven years, about thirty minutes away from where he lived at 118 Prospect Street with his wife Amy (née Kinnings) and four children. By 1915 he had been promoted to the position of colliery stallman, an overseer’s role which perhaps could have been the start of a promising career had disaster not struck later that year. On Thursday 17 June, George was working alongside fellow stallman Henry Jenkins when at around 12.30 midday they heard a crash. Henry, on hearing George cry out, ran to his aid only to discover that he had been almost completely buried under the fallen pit roof, fracturing his spine and inflicting several other internal injuries. He was quickly pulled out and conveyed to his house on Prospect Street but it was too late, he died of his injuries almost three weeks later on 5 July. The coroner’s inquest which followed returned a verdict of ‘accidental death’ but noted that a slight crack in one of the pit’s supporting posts had been detected before the accident and that nothing had been done about it. His funeral took place on Thursday 8 July at Alfreton Cemetery. At the following Monday’s meeting of Alfreton Council his father Thomas received a vote of condolence from the other councillors. He was, he said “passing through troubled waters, ” having lost his son-in-law (John George Smith), his wife and his son in such a short space of time (The Derbyshire Courier, 10 July 1915, p. 5, col. 4). Sadly, 1916 would see no reversal in the England family’s fortunes.

Edwin England, Thomas’s youngest son, was born on 8 November 1893. His three older brothers were all at least ten years older than him and had already started their first jobs by the time he came along. It therefore seems likely he would have been closer to his sisters growing up, all of whom were nearer to him in age. From the 1911 census we know Thomas and Mary Ann had a total of thirteen children together, but sadly only nine of them appear to have survived infancy. Of the four who died the only name we know is that of Ernest Edward England, who was born in early 1892 and died on 27 November that same year. Although infant mortality rates were much higher back then I believe the timing of Ernest’s death must have had an impact on how Edwin was raised, even his name sounds like it may have been intended as a tribute. Having gone through the experience of losing a son the year before would surely have made Edwin’s birth and survival feel even more special, and it’s easy to imagine him as the youngest boy in the family becoming something of a favourite. Unlike his older brothers, when Edwin started work his father would have been successful and influential enough to help him out, and perhaps it was Thomas’s recommendation which had secured him a clerk’s job at Birchwood Colliery by the time he was eighteen (The Derbyshire Courier, 4 November 1916, p. 1, col. 2).

While as a young man Edwin may have seemed poised to follow in his father’s footsteps, there was of course a key difference between him and his father. When Thomas had turned twenty one it had been 1871 and Britain was at peace. When Edwin reached the same age the year was 1914. On 4 August that year Britain declared war on Germany, and Edwin, as the only England brother not employed in a reserved occupation would have faced enormous social pressure to enlist in the army. On 9 June the following year he enrolled as a private in the 9th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters at Nottingham, and a month later he left Liverpool on a ship bound for the North Aegean. On 7 August he disembarked with his battalion at Sulva Bay, Gallipoli.

The events of that famously ill-fated campaign to capture the Dardarnelle Straits from the Ottoman army hardly need repeating here, but the 9th Battalion are said to have “maintained stout hearts and a soldierly spirit” despite heavy losses. Edwin apparently escaped the battle “without a scratch” (The Derbyshire Courier, 4 November 1916, p. 1, col. 2) before his battalion were evacuated to Egypt via Crete in December. In July 1916 they were redeployed to France, and on 26 September 1916, at the Battle of Thiepval Bridge, the first large offensive of the Battle of the Somme, Edwin was killed in action near the village of Ovillers-la-Boisselle. He likely fell during the capture of the German Hessian and Zollern trenches however his body was never recovered. He was twenty two. His memory is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial in France, and on his parents’ headstone in the churchyard of Swanwick Baptist Church.

Unlike George and Edwin, Thomas England’s second son Thomas England Jr. would go on to outlive their father by several decades, however his name is conspicuously absent from the list of mourners at his funeral. Apparently, his wife Maud did attend (identified as “Mrs. T. England (daughter-in-law)” in The Derbyshire Courier, 2 March 1918, p. 1, col. 5), which makes Thomas’s unexplained absence even stranger. There are a number of possible explanations for this of course, but before exploring these let us first take a look at his early life. To avoid confusion with his father I will from this point on refer to Thomas Jr. as ‘Tom,’ as this is the form he used on two of his sons’ baptism records and therefore was probably the name by which he was best known.

Born on 28 July 1878, by the time he was thirteen Tom had already left school and was listed as an ‘errand boy’ in the 1891 census. He would likely have started down the mines not much later, as by 1901 he is recorded as a coal miner. It is unknown which pit he was based at then but he would probably have been working for the Babington Coal Company at Birchwood Colliery alongside his brothers George and Edwin. At around this time, just up the road from the England family home on Park Street was a china shop at number 16 King Street run by a widow named Mary Ann Ling, who lived above it with her daughters Maud and Olive. Maud (b. 17 April 1881, Ripley, Derbyshire – d. 22 July 1950, 119 Holbrook Street, Heanor, Derbyshire) would undoubtedly have helped her mother out from time to time at the shop, and it was perhaps here where Tom met her for the first time. It’s tempting imagine a romance blossoming between them over the counter during Tom’s frequent visits as an young errand boy, but that’s maybe a little fanciful. Their wedding, which took place on 16 November 1901 at Alfreton, has already been described elsewhere but I’ve reproduced their marriage certificate below which gives their names, their witnesses, and their fathers’ names and occupations.

Tom and Maud appear to have left Alfreton shortly after getting married. They had one son there in 1902 but the rest of their children were all born in Langley in south Derbyshire, including my grandfather Frederick England. Their names were:

- Albert (b. 6 September 1902, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 17 October 1948, The City Hospital, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire)

- Arthur (bp. 15 December 1904, Heanor, Derbyshire – d. c. May 1905, Derbyshire)

- Harry (bp. 23 January 1908, Heanor, Derbyshire – d. 26 January 1958, 7 Grace Crescent, Heanor, Derbyshire)

- Frederick England (b. 23 July 1912, Langley, Derbyshire – d. 24 September 1980, Codnor, Derbyshire)

- Herbert Kenneth (b. 30 April 1915, Langley, Derbyshire – d. 27 March 1984, Derby, Derbyshire)

- Norman (b. 23 April 1921, Langley, Derbyshire – d. c. May 1983, Nottinghamshire)

In the 1911 census the family were living in a three-room house at 15 ‘Odessa Yard’ in Langley. I initially had some difficulty locating the present-day site of this address but after checking the house numbers which came before and after the Englands in the census schedule I now believe they were actually based at 15 Laceyfields Road. Like his older brother George, Tom was a coal hewer, and we know from an article in The Nottingham Evening News (12 Nov 1910, p. [4], col. 4) that he was employed by the Butterley Company Ltd. at the New Langley Colliery (Thomas had been a witness to a recent pit fatality and was giving evidence during the inquiry). In 1912 he would most likely have participated in the National Coal Strike, as well as the General Strike of 1926. By then though he was no longer working as a hewer but an ‘onsetter’ (according to an application for a copy of his son Frederick’s birth certificate dated 4 August 1926). Onsetters were in charge of loading the cages at the bottom of the shaft which conveyed miners to the surface, as well as giving the appropriate signals to the winding engineman. Their equivalent above ground was known as a ‘banksman,’ which is the occupation Tom gave the following decade in both his son Frederick’s marriage certificate from 1938 and in the recently-released 1939 register.

By this time he was sixty one years old and living at 98 Holbrook Street in Heanor with his wife Maud and their son Kenneth (Frederick and his wife Mary also stayed with them for a period in the late 1930s before moving across road to number 119). Tom died in 1944 while his sons Frederick and Norman were away fighting in Europe. Unusually for the time he chose for his remains to be cremated rather than buried, which was perhaps appropriate for a man who had already spent so much of his life below ground.

Although I know a great deal about my grandfather Frederick from my mother, and over time have managed to piece together almost as much about his grandfather Thomas England Sr., many of the details of Tom’s life are still shrouded in mystery. I have neither the wealth of anecdotal information about him which I have for his son, nor the extensive news coverage on his activities which I have for his father, and that has somehow always made him even more intriguing to me. This curiosity has been fed by the two major pieces of anecdotal information I do have about him: that he was an excellent fiddle player and a heavy drinker.

The former has always struck me as unusual. Given the time and place in which he grew up, if Tom was musically inclined one would probably have expected him to gravitate towards the local colliery brass band, or perhaps some form of sacred music (which I’m sure his father would have preferred). In contrast to these more traditional, community-based forms of music-making, to me playing the fiddle feels more individualistic, more romantic and possibly a little wilder. This image of him seems to fit well with the fact that he was also known to enjoy a drink. Although it was fairly common for miners to be heavy drinkers at this time, the very fact that this is one of the few pieces of information about him which has been passed down to me suggests his habit was somehow exceptional he may have suffered from alcoholism (Maud apparently had to hide money around the house to stop him spending it on drink). This is pure speculation, but based on the few details I have about him, Tom seems like very different character to his father Thomas England Sr., the respected town councillor, Freemason and deacon, so perhaps his absence from his father’s funeral was due to some kind of falling out? Alternatively Tom may just have been sick or unable to get out of work that day, and his drinking habit could have developed later (perhaps triggered by the deaths of his parents and two brothers in the space of five years). Like so much else about his life, the truth is now lost to us and we must make do with what have the faculty to imagine.

* * *

Although I fully intend to return to Tom’s sons in future posts, because their stories are inextricably tied up with those of several living persons I am ending my in-depth history of the England family here in order to to preserve their privacy. In the posts to come I’ll be turning my attention to the family of my grandfather Frederick’s mother, the Lings, a family so different to the Englands with their deep roots in the Derbyshire coalfield it’s a surprise their paths ever crossed.

Sources:

Baker, Chris. “Sir Ian Hamilton’s Fourth Gallipoli Despatch.” The Long, Long Trail. Accessed 2 March, 2016. http://www.1914-1918.net/hamiltons_gallipoli_despatch_4.html.

Elliot, Brian. Tracing your coalmining ancestors: a guide for family historians. Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2014.

Stone, G. Strike action at Swanwick Colliery during the Nineteenth Century. Matlock: Derbyshire County Council, 1998.