This is the second in a series of posts on the history of my grandfather Frederick England’s maternal ancestors the Lings, the first of which can be read here. This part mainly focuses on Frederick’s great-grandfather George Ling and covers the period between his birth in 1824 and the death of his widow in 1906.

* * *

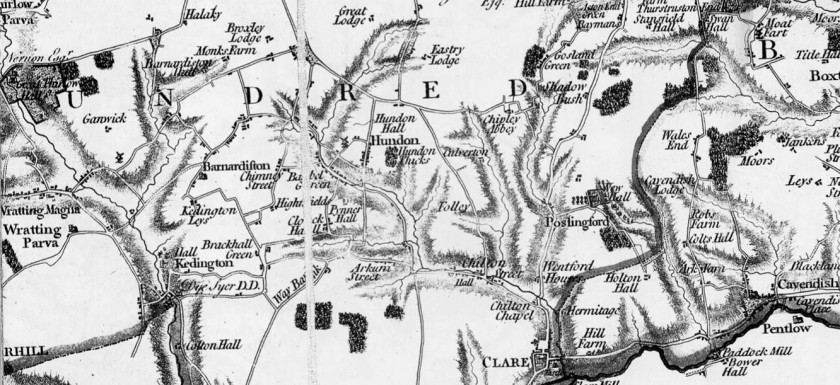

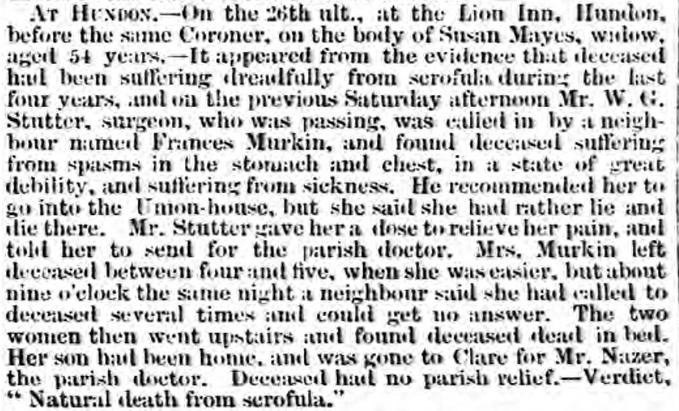

On 19 September 1824, a parish clerk in Hundon, Suffolk, recorded the baptism of a ‘base born’ (illegitimate) pauper’s son named George Ling. As we saw in the previous post, just three months later his mother Susan married an agricultural labourer named Samuel Mayes, the timing of which strongly suggests he may have been the boy’s father. Unlike his younger, legitimate brothers John and Thomas Mayes however, George did not share their father’s surname, so throughout his childhood his ‘bastard’ status would have been painfully self-evident to everyone in his community. Not only were illegitimate children subjected to one of the most pervasive and persistent social stigmas of the age (it was widely assumed they would share their parents’ ‘loose morals’), they faced economic discrimination too, as until the Twentieth Century they had no rights to inheritance. This perhaps explains why George had already left home by of the time of the 1841 census, when he would have been just sixteen, for the idea of starting a new life somewhere unburdened by his past must have been extremely attractive to anyone in his situation.

In 1841 George was working as a ‘male servant’ in the house of John Rutter of Bayments Farm in Stansfield, although his actual duties would probably have involved farm work rather than domestic service. By 1848 he had begun a relationship with a young woman from Keswick in Cumbria named Elizabeth Hartley (b. c. 1821), who on 28 February the following year gave birth to their first son, John. Although Elizabeth took the name Ling and is recorded on all later censuses as George’s wife, his will reveals that they had never actually been married, as in it he refers to their sons and daughters as “my illegitimate children familiarly known as…Ling”. After spending several years trying in vain to track down George and Elizabeth’s marriage certificate, this passing reference in his will had managed to solve one great mystery while simultaneously presenting another. Why, if they were living together as man and wife, sharing a surname and passing their children off as legitimate in public, did they not just get married? Even more confusingly, although no marriage certificate exists, there is a record of a couple in Kings Lynn with their names calling the banns in December 1846. I believe the most plausible explanation for all this is that one of them was already married, most likely Elizabeth who was older and came from further away, and that this was discovered before they could be wed.

This might explain why at the time of their son’s birth in 1849 they were living on Beckett Square in Barnsley, over a hundred miles from where either their families lived. Another explanation could be that George had been serving an apprenticeship there, as on John’s birth certificate he is recorded as an umbrella maker, a skilled trade which could have required several years’ training. Whatever the reason, they did not stay in Barnsley long, as the census of 1851 shows the family had moved to Mansfield in Nottinghamshire by then. Rather curiously they are shown running a large lodging house at 19 Chandlers Court, and George was no longer working as an umbrella maker but a bricklayer’s labourer. He and Elizabeth had one daughter there, Emily, before moving again to Alfreton in Derbyshire, where they would remain for the rest of their lives. They had eight children in total, whose names were:

- John (b. 28 February 1849, Beckett Square, Barnsley, Yorkshire – d. 13 December 1894, 12 Silver Street, Doncaster, Yorkshire)

- Emily (b. 8 April 1851, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire – d. 15 January 1925, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- William (bp. 2 October 1853, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. August 1926, Chesterfield, Derbyshire)

- Elizabeth (bp. 2 December 1855, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. November 1925, Chesterfield, Derbyshire)

- George (b. 13 July 1857, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. May 1940, Chesterfield, Derbyshire)

- Susannah (b. 14 August 1859, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 22 April 1936, Alfreton, Derbyshire)

- Sophia (b. 8 July 1861, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. c. August 1932, Derbyshire)

- Thomas (b. 25 July 1865, Alfreton, Derbyshire – d. 27 April 1902, Chesterfield, Derbyshire)

The baptism record for George and Elizabeth’s second son William from 1853 shows that George had initially continued working as a lodging house keeper after moving to Alfreton, but by their daughter Elizabeth’s baptism in 1855 he was giving his main occupation as ‘general dealer.’ Similarly, in the 1861 census his occupation is recorded as ‘marine store dealer,’ and it is worth taking a moment to look at exactly what was meant by these slightly misleading terms. A ‘general dealer’ usually referred to a hawker rather than a shopkeeper, and despite what their name suggests ‘marine store dealers’ did not necessarily sell mariners’ equipment, normally this was just a term for general junk or scrap dealers. Interestingly, these are both occupations which were traditionally associated with Travellers and Gypsies, as was umbrella making. It is also notable that the majority of George and Elizabeth’s descendants went on to work in typical traveller occupations (general dealers, china and earthenware dealers, hawkers, even fairground showmen), and many led nomadic lives in caravans. It is unclear where exactly this affinity for the travelling lifestyle came from, as George clearly hailed from a settled agricultural community. One possibility is that it it came from Elizabeth as we know nothing about her life before 1849, therefore it is possible she came from a Traveller or Gypsy family.

Elizabeth died at the age of fifty on 12 January 1871 of phthisis, a wasting disease often caused by tuberculosis. Her funeral took place at St Martins Church in Alfreton three days later, though oddly her name is recorded in the parish registers as ‘Mary Elizabeth Ling.’ In her death certificate her husband George is said to have been present at her death, and his occupation is given as ‘inn keeper.’ Since about 1864 he had been running the Royal Oak Inn at 10 King Street in Alfreton, and over time this appears to have gradually replaced general dealing as his main source of income. After 1871 he consistently gave his occupation as ‘publican’ in the census but he never completely abandoned his earlier trade as a marine store dealer. His will mentions two such shops, one in Alfreton and one in Chesterfield, as well as a greengrocers, although he presumably employed others to run these on his behalf.

His possession of these three businesses at the time of his death demonstrates just how far George had come since leaving Hundon, and after his acquisition of the Royal Oak in the mid-1860s his name begins to appear in local news stories with increased frequency. Many of these articles relate to incidents involving other people which merely took place on his premises, but they nonetheless help build up a picture of what his day-to-day life must have been like. One such story was that of Joseph Yarnold, who was charged with stealing one of George’s cups to give to a woman but was found not guilty after the jury dismissed it as “the act of a half-witted man” (The Derby Mercury, 11 January 1865, p. 8, col. 6). A second describes the inquest following the death from starvation of a sixty year old man from Sheffield who had been refused entry at several lodging houses before finally being taken in at the Royal Oak (The Derby Mercury, 19 October 1870, p. 2, col. 4).

Other stories relate more directly to George, such as the report on a court case he brought against the Meadow Foundry Co., which he claimed had supplied him with burnt scrap iron (The Derbyshire Times, 17 December 1873, p. 3, col. 5). Another from the following year describes “a general meeting of the Licensed Victuallers‘ Society, held at the home of Mr. George Ling” at which the men pledged to support their local Conservative candidates at the forthcoming general election (The Derbyshire Times, 7 February 1874, p. 8, col. 6). This would have been only the second election at which George was eligible to vote, the first being that of 1868 which was held the year after the Reform Act enfranchised the vast majority of male householders. As the secret ballot was still two years away at this time we can see from the 1868 poll book that he was clearly a habitual Conservative supporter, and had voted for the unsuccessful (but wonderfully-named) Conservative candidates Gladwin Turbutt and William Overend that year.

In George’s final years he found companionship in a Yorkshire widow ten years his junior named Isabella Muff (née Brooks, b. 30 May 1834, Bradford, Yorkshire – d. c. February 1906, Middlesbrough, Yorkshire). They were married in Chesterfield parish church on 9 January 1873, and their marriage certificate (reproduced below) is notable for three reasons. Firstly there is the fact that it exists at all, which this tells us that there was no legal impediment to George getting married by this time. Presumably therefore it had been his late partner Elizabeth’s marriage to another man which had prevented her from marrying George, rather than any of his previous relationship of his. Secondly, it tells us that neither of them were literate because they both left ‘marks’ rather than signing their names. This is somewhat surprising given that George was already managing a number of businesses by then. Thirdly, it reveals that George had been attempting to conceal his illegitimacy, as he falsely gives his father’s name as ‘Samuel Ling,’ rather than ‘Samuel Mayes.’ There is further evidence for this cover up in the census returns for 1861 to 1901, which record George’s younger brother Thomas Mayes as ‘Thomas Ling.’ Thomas, by then a general labourer, had moved to Alfreton to live with George following their mother Susan’s death in 1859, and presumably took the Ling name in order to spare his brother any embarrassment. Interestingly, like George, Thomas also fudged the identity of his father on his marriage certificate from 1864, recording his name as ‘Samuel Mayse Ling’.

According to one of his descendants, Linda, who I met via Ancestry, George was apparently known to ‘cut his corns’ with a knife, and on one occasion this led to a severe foot infection. In an age before penicillin this could be fatal, and upon visiting his doctor George was immediately advised to prepare his will. He died on 18 November 1884 at the age of sixty of gangrene and an abscess of the foot, but his death certificate also reveals that he had been suffering from acute diabetes. Two days later he was buried in St Martins churchyard in Alfreton. His £1,807 12s. 11d. estate was divided among his children and Isabella, however there is reason to believe his widow may have been unhappy with this settlement. According to another oral tradition I learned through Linda, one night, presumably after George had died but before his wealth had been distributed, Isabella had locked herself in their bedroom and emerged several hours later wearing a large coat, claiming she was going for a walk. She would never return however, having sewn as much of George’s money as she could into the coat’s lining. If true this story could explain why none of George and Elizabeth’s children are said to have liked her. Three years later she married her third husband Lister Rhodes before moving to Middlesbrough, where she died in 1906 at the age of seventy one.

* * *

Over subsequent generations some of George and Elizabeth’s descendants would completely assimilate into their local communities while others embraced travelling lifestyles, and it’s possible to trace the origins of both tendencies back to this rather unconventional couple. In the next post we will look at what became of their eight children, including Maud Ling’s father John.