This is the third in a series of posts about the Mills family, the direct male-line ancestors of my maternal grandmother Julia Mary Mills. In this part I trace the stories of her great-grandfather Reuben’s generation who lived during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

* * *

The children of John and Elizabeth Mills were among the first members of their family to abandon their ancestors’ rural way of life in search of work in the towns. In the previous post I speculated that this may have been a consequence of the Great Depression of British Agriculture which began in 1873, but the census shows that at least two of the Mills children left their parents’ home in Sutton Bonington in the 1860s, a time of relative prosperity. There could be a more local explanation however, as at around this time their landlord’s manor at West Leake had been put up sale (East Leake & District Local History Group, 2001, 8) and the threat of change would have led to a general unease among the agricultural workforce.

The first to leave was John and Elizabeth’s eldest son Thomas Mills (b. c. March 1830, West Leake, Nottinghamshire), who had already moved to Codnor in Derbyshire by 1861. That year’s census records him and his wife Elizabeth (née Hywood) living there with their two children George and Emma on Jessop Street, and Thomas’s occupation was given as ‘labourer on coal field’. Although the fact that Thomas’s wife hailed from Bolsover probably explains how the family ended up in Derbyshire, his occupation suggests the area’s well-established coal mining industry was another likely attraction.

So-called open-pit mining had been in operation at Codnor since at least the fifteenth century, but as Stuart Saint explains:

It wasn’t until the Butterley Company was established in 1790 that mining in the area began to get more advanced. The company invested huge amounts of money into mines that penetrated the coal and ironstone seams deeper than ever before. The local community grew from a small agricultural based workforce to a rapidly growing industrial one. The increasing population needed more housing and many of the streets in Codnor did not exist until the mid 1800s, when they were built to accommodate hundreds of workers needed for the many mines in the area.

One of these streets was Jessop Street, built in around 1860 and named for William Jessop, one of the Butterley Company’s founders, where Thomas and his family lived until at least 1881.

By that year’s census Thomas was recorded as an ‘iron worker’, so it is likely he had begun working at the Butterley Company’s vast ironworks just north of Ripley. Although the company was one of the most distinguished engineering firms in the country, and had been responsible for such innovations as the great arched train shed at St Pancras Station, they would nonetheless face calls from their employees to improve pay and working conditions later in the century. These calls were initially fiercely resisted by the company, who fired eleven workers in 1874 for their role in a strike over pay, although no official charges were ever brought. Thomas was not among those who lost his job as a result of the strike, however given his union activity later in life (more of which later) it seems plausible he could have participated in it.

Like any under-regulated nineteenth century workplace, the Butterley ironworks would also have been an incredibly dangerous place to earn a living, especially for men like Thomas who were forced to work well into old age. On Thursday 23 January 1890, Thomas, by then almost sixty, accidentally dropped a heavy iron plate he had been picking up, which fell and crushed one of his legs. Upon his arrival at Derby Infirmary the doctors were forced to amputate the smashed limb.

Fortunately Thomas survived the procedure, and the following year’s census shows he had already found work as a general labourer, one would hope with the assistance of a new wooden leg. Ten years later in 1901 he was recorded as a ‘head furnace weighman’ at the ironworks, a more prestigious but less physically demanding role better suited to a seventy one year old amputee. His work here would have involved leading the team who checked, weighed and recorded the coke and iron ore being charged into the blast furnace. A unique insight into the lives of the Butterley Company’s workforce at this time can be gained from this rare footage from 6 October 1900, which shows workers leaving the ironworks at the end of a long day’s work.

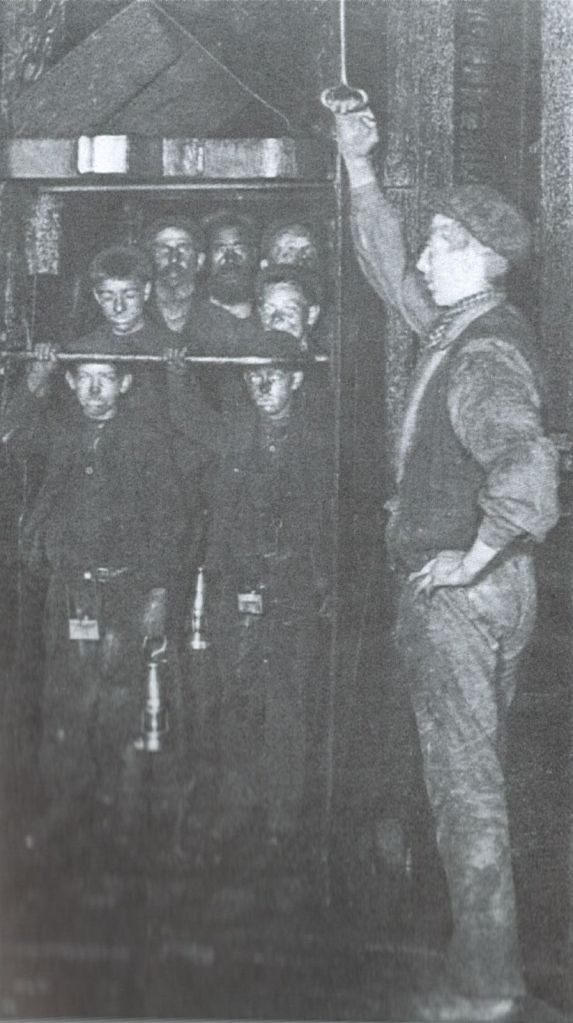

At some point before 1911 it appears Thomas returned to the coal mining industry, as in that year’s census his occupation was given as ‘colliery checkweighman (above ground) previously’ (i.e. recently retired). This job, while similar to what he had been doing at the ironworks, differed in that he would have been working not for the enrichment of the Butterley Company but for the benefit of his co-workers through their union, the Derbyshire Miners’ Association. At this time miners were paid by the amount of coal produced, so it was important the weights recorded were accurate. Two weighmen were therefore employed, one working on behalf of the company, and a trade union representative (a ‘checkweighman’) elected by the miners to verify his findings. The photograph below taken at Denby colliery in 1898 shows the type of weighing machine Thomas would have used on a daily basis. Note also the elderly one-legged man on the right. As Denby colliery was situated only about an hour’s walk from Thomas’s home on Nottingham Road, it is tempting to think the man in the picture could be him, even though the census suggests he was still working at the ironworks at the time.

It is interesting to compare Thomas’s story to that of Thomas England (see There’ll Always Be An England (Part 2)), whose grandson Frederick would go on to marry Thomas Mills’s great-grandniece, my grandmother Mary, in 1938. Not only did both men survive potentially fatal accidents at work, but as a result both ended up as colliery weighmen instead of manual workers. Unlike Thomas England though, Thomas Mills’s accident happened near the end rather than at the beginning of his working life, which perhaps explains why his career did not benefit to quite the same extent. He died in the last quarter of 1914 at the age of eighty four.

It is unclear what happened to John and Elizabeth Mills’s second son Charles (b. c. 1833, Sutton Bonington, Nottinghamshire). Oddly, there is a baptism record for him from 8 June 1845 at Sutton Bonington, when he would have been around twelve, but after that we can only speculate. Charles’s baptism appears to have been a joint ceremony with his younger brothers Reuben (b. c. December 1835, West Leake, Nottinghamshire) and John Jr. (b. c. June 1845). Reuben we will return to shortly, but John Jr. is another son whose later life is a mystery.

We know a little more about their younger brother, John and Elizabeth’s last child Robert Mills (bp. 11 October 1849, Sutton Bonington, Nottinghamshire). Born almost twenty years after their eldest, by the time he was twenty one Robert was still living at his parents’ house but working as a labourer at an iron foundry. Six years later he married Charlotte Musson, another Derbyshire girl from Heanor, on 18 December 1877. The next census shows that by 1881 they had left Sutton Bonington and moved to Leake Road in nearby Normanton on Soar. It also shows that Robert had begun working as an agricultural labourer, an occupation he would still hold ten years later, and that Charlotte was employed as a hosiery seamer. The final census on which Robert appears records that by 1891 his family had moved back to Sutton Bonington where they lived at Rectory Farm, a short distance away from where he had grown up at Pit House. Robert died at the age of only forty nine and was buried on 1 September 1899 at West Leake. Over the course if their marriage he and Charlotte had twelve children together, and after Robert’s death many of them went with their mother when she returned to Heanor to work as a charwoman.

* * *

We return now finally to Rueben Mills, John and Elizabeth’s third son and my grandmother’s great-grandfather. Like his brothers, Reuben grew up at Pit House in Sutton Bonington, but by the time he was sixteen he was working as a farm servant for a widow named Rebecca Oakley in Wilford. According to the 1851 census, Oakley’s farm covered thirty acres and employed three other servants (two domestics and a charwoman). Farm servants like Reuben differed from agricultural labourers in that they typically lived in the farmer’s house and received board as part of their pay. As a result, they were considered to be “just a little further up in the pecking order” according to Crawford MacKeand (2002):

If single, he “lived-in” and bed and board were part of the contract for hire, and if married, he was provided with a house or a cottage, with possibly some grazing rights or strip of land to use and some provisions for the family. Cash wages were maybe less than 40% of total income. Hiring could be a continuation of existing employment or a new contract established at a “hiring fair”, and was normally for a one year period, or at least six months.

[…]

In some areas the Farm Servant was also known as a “confined man” and this was a desirable status to be aimed at. He, almost always he, was skilled typically in horse or other livestock care…and was therefore employed continuously year round…The Agricultural Laborer on the other hand was paid day wages, hired on a short term as and when work was needed, and therefore much more characteristic of arable farming, for planting, hoeing, reaping etc. He or she was given no accommodation, often operated as part of a gang under a contractor, and received only wages.

It it may be hard for those familiar with Wilford as a Nottingham suburb to imagine it populated with farm servants and agricultural labourers, but in the mid-nineteenth century it still retained much of its original rural character. It is possible to get an idea of what the village looked like in Reuben’s day from the surprising number of Victorian oil paintings of it. Writing in 1914 Robert Mellors even noted that “Wilford has the honour of being the most painted, and best illustrated village in the county”, and that there were several paintings referring to it at the Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery:

There is a view of the Trent, shewing the church, ford, etc., painted by Thomas Barber, about 1840; a view at Wilford from the Trent, “Looking to the Castle,” by Benjamin Shipham; “Wilford Ferry” (The Cherry Eatings) about 1858, by John Holland, Junr, shows a boat being towed over, full of passengers, while a crowd of ladies wearing crinolines, and gentlemen top hats, are waiting their turn. The vendors of cherries are doing a busy trade.

The three paintings described by Mellors can be seen below, and more can be browsed via the Culture Grid website.

Reuben did not settle permanently in Wilford however. By April 1861 he had moved back in with his parents at Sutton Bonington, and that year’s census records his occupation as ‘agricultural labourer’, suggesting something of a downturn in his fortunes. This would prove to be a temporary state of affairs though, as by November he was once again working as a farm servant twenty two miles away at Langar Lodge. Soon after he would be joined there by his new wife Charlotte (née Wilcox), who he married on 25 November 1861 at St Helena’s church in West Leake.

Charlotte was the third daughter of an agricultural labourer named Thomas Wilcox (b. 1797, Beeston, Nottinghamshire – d. c. February 1872, Nottinghamshire) and his wife Mary Attawell (b. 27 June 1799, Bradmore, Nottinghamshire – d. 1862, Stanton On The Wolds, Nottinghamshire). She was born on 2 May 1840 in the village of Stanton On The Wolds, Nottinghamshire, and in 1861 had been working as a domestic servant for a farmer named Thomas Hardy on Main Street, West Leake. As Reuben would have been living only half a mile away at the time it is unsurprising that the two of them eventually crossed paths, they may have even shared the same employer. Whatever the circumstances of their first encounter, sometime around August 1861 Charlotte became pregnant with Reuben’s child, and six months after their wedding she gave birth at Langar Lodge on 9 April 1862. The boy who was christened George Mills on 11 May that year was my great-great-grandfather.

Shortly after their son’s birth Reuben and Charlotte left Nottinghamshire and rural life altogether to settle in Codnor, where Reuben’s brother Thomas’s family had moved a few years earlier. The 1871 census records both families living on Jessop Street just eight houses apart, and like his brother Reuben’s first job here was at the local colliery. There he worked as a banksman, which involved directing the loading and unloading of the cage that carried men from the top of the pit down to the coal face below.

The family stayed in Codnor for at least six years, during which time they had the following three more children:

- Ellen (b. c. 1865, Codnor, Derbyshire)

- William H. (b. c. November 1866, Codnor, Derbyshire)

- Elizabeth (b. c. 1870, Codnor, Derbyshire)

At some point before 1877 they moved back across the county border to Underwood in Nottinghamshire, another mining village, where they had their fifth and last child:

- John Thomas (b. c. October 1877, Underwood, Nottinghamshire)

Unlike his brother Thomas however, Reuben would not stay in the coal industry for long. The 1881 census shows that by then he had returned to farming, and that his family had resettled in Ratcliffe-on-Soar near where he grew up. Of Reuben and Charlotte’s children, sadly only George, William, Elizabeth and John Thomas were living with them at this point, suggesting their eldest daughter Ellen may have died. Their oldest sons George and William, then eighteen and fourteen, had started work as farm servants, while Reuben was once again an agricultural labourer, an occupation he would continue to hold for the rest of his life.

Sometime before the next census in 1891 Reuben and Charlotte moved for the fourth and final time to Kegworth in Leicestershire, where they lived on Nottingham Road. Their eldest son George had moved here a few years earlier, and many of their descendants would continue to live here well into the twentieth and even twenty first centuries. By this time all Reuben and Charlotte’s children except William and John Thomas had moved out, so they had been obliged to take in a lodger, a plumber and gas fitter named William Smart who was still living with them in 1901 and 1911.

Charlotte and Reuben died within just five days of each other on 18 and 23 November 1915 respectively. Charlotte’s cause of death at the age of seventy five was given as ‘old age [and] myocardial degeneration’, and Reuben apparently succumbed to ‘senile decay’ aged seventy nine. While Reuben died at the family home on London Road, sadly Charlotte’s last recorded address was the Shardlow Union Infirmary and Workhouse, suggesting she may have been unwell for some time.

The informant on Reuben Mills’s death certificate was his daughter-in-law Fanny Mills, who was also present at the death. Fanny was the wife of Reuben’s first son George and my great-great-grandmother, and I will be looking at this next generation of Millses in the next post.

Sources

East Leake & District Local History Group. 200 Years of Basketmaking in Ratcliffe-on-Soar, West Leake and East Leake, Nottinghamshire. East Leake: East Leake and District Local History Society, 2001.

MacKeand, Crawford. “Farm Servants and Agricultural Laborers”. The Wigtownshire Pages. 2002. Accessed 24 March, 2017. http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ainsty/articles/profession/aglab.html.

Mellors, Robert. “Wilford: Then and Now.” Nottinghamshire History. 2010. Accessed 26 March, 2017. http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/articles/mellorsarticles/wilford6.htm.

Saint, Stuart. “Mining.” Codnor & District Local History & Heritage Website. Accessed 9 March, 2017. http://www.codnor.info/mining.php.