This is the much-delayed fifth and final post tracing the history of the Mills family, focusing specifically on my great-grandfather Harry Mills, his siblings, and my maternal grandmother Julia Mary Mills. To catch up on their story so far, see the first post in this series, Going through the Mills (part 1).

* * *

The seven surviving children of George and Fanny Mills all grew up in their family home at 17 Loughborough Road, Kegworth, in the 1880s and 1890s, before moving to London Road sometime before 1901. Their eldest son John George Mills (b. 13 May 1886, Kegworth, Leicestershire), better known as ‘Jack’, was the first to enter work, and is recorded as a pantry boy in that year’s census. This was considered one of the lowliest forms of domestic service, and would have involved assisting the kitchen staff of large houses with basic tasks like washing dishes, peeling potatoes and sweeping floors.

In 1909, at age twenty two he married Elsie Ethel Mills (b. c. November 1889, West Leake, Nottinghamshire), a dairy engineer’s daughter who by the time of their wedding was already several months pregnant with their first child. Over the next three years they would go on to have two daughters together, whose names were:

- Edith (b. 19 July 1909, Kegworth, Leicestershire – d. November 2001, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire)

- Frances Hilda (b. 21 August 1911, Kegworth, Leicestershire –5 August 2010, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester, Leicestershire)

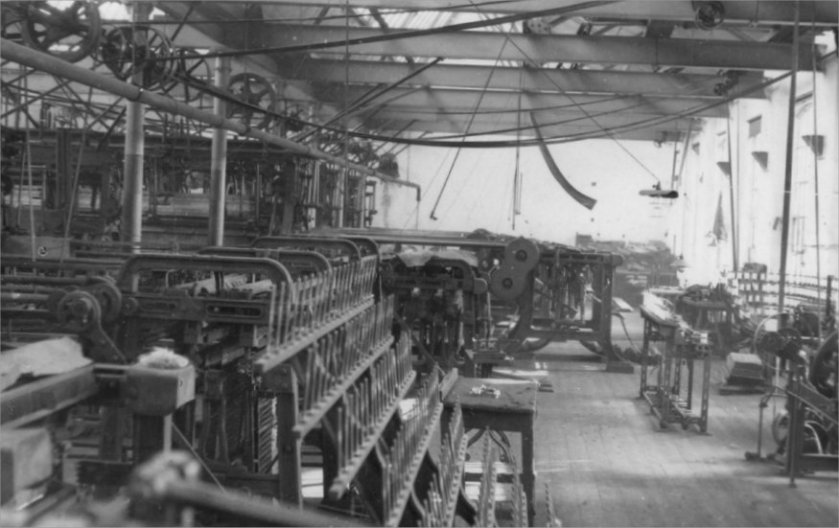

The 1911 census records the family living in a row of cottages off Kegworth High Street known as ‘The Rookery’. By this time Jack was working as a lace maker or twist hand, the same occupation he gave decades later in the 1939 Register, and before that he is said to have been a stockinger. Lace making had been an important part of Kegworth’s economy since the industrial revolution but by 1911 the majority of the village’s lace workers like Jack would have been employed at A. Leatherland’s factory at Borrowell. The work here would have been very different to the kind lace makers would have known a century earlier, as Sheila A. Mason writes:

During the period 1820 to 1860 the hand-operated lace frames were gradually replaced by steam-driven, factory-based machines. Hours were regulated by the steam boiler; power and heat were usually provided between 4 am and midnight Monday to Friday and 4am to 8pm on Saturday. Lace machines required a constant temperature so the factories were heated to between 65 and 70 degrees. A factory containing 100 machines would have about 500 workers.

Lace machine operatives, called ‘twisthands’, were male and as the machines were lubricated by black lead, (graphite), and oil they often finished work as black as coal miners.

Until the 1920s shift work was a feature of the industry and the twisthand and his mate, known as a ‘butty’, worked five or six hour shifts of five or six hours a shift; the first man usually working 4am to 9am and 1pm to 6pm and the second man 9am to 1pm and 6pm to midnight. Twisthands were paid by the amount of work produced, not by the hours worked, and take-home pay varied considerably according to the type, width and speed of the machines and the type of lace being produced.

This picture is confirmed by his second daughter Frances, who recalled taking her father’s billycan and sandwiches to the factory as a little girl and finding the noise frighteningly loud. In later years he went on to work at Slack & Parr Ltd., an engineering factory on Sideley Road.

Outside work however, we know from his descendants that Jack was also an accomplished musician, and that he played the euphonium in Kegworth Brass Band. Contemporary newspaper accounts show both bands performing at a huge number of functions over several decades, including military parades, dances and country fairs, highlighting the centrality of brass bands to northern and midlands culture at this time.

According to Dave Russell (1997, p. 213-214):

The membership of brass bands … was exclusively male and solidly working-class. […] Bandsmen always described themselves as ‘working men’, as did middle class observers, whether friendly or hostile. The majority, judging by the evidence of oral testimony and the personal details that appeared in the band press, appear to have been from the skilled or semi-skilled sections of the working class. Hardly surprisingly, given the social and geographical base of the movement, many, perhaps a majority, were miners. Others simply reflected the occupational structure of their area.

From this description it is clear Jack’s background was fairly typical for a bandsman of this era. Despite the bands’ humble backgrounds and lack of formal training however, by the Edwardian era the best of them were attracting crowds of over 70,000, and at the peak of their popularity it is thought most communities in England of over a thousand people supported an amateur brass band of some kind. Consequently, and with some justification, the brass band movement in England has been described by Russell as “one of the most remarkable working-class achievements in European history” (p. 205).

Sadly Jack’s wife Elsie died prematurely in 1921 when she was only thirty one years old. Their daughters Edith and Frances would have been eleven and nine. Four years later, Jack married a second time to Lucy Ethel Marchant (b. 8 April 1896, Kegworth, Leicestershire – d. c. February 1971, Nottinghamshire), with with whom he had two more children:

- Eileen (b. 10 April 1926, Kegworth, Leicestershire – d. 14 June 2012)

- John (b. 7 July 1930, Kegworth, Leicestershire – d. c. April 2006, Rugby, Warwickshire)

Shortly before his death, my mother recalls meeting Jack and his family for the first time in Kegworth when she was around ten years old, and noted how much he resembled her grandfather Harry (as well as how much his daughter Eileen looked like her mother Mary). Jack died on 11 September 1963 at the age of seventy seven. His probate record shows his effects at the time were £341 15s, which went to his widow Lucy.

Jack’s younger brother Alfred William “Fred” Mills (b. c. February 1888, Kegworth, Leicestershire) was recorded working as a farmer’s boy in the 1901 census at the age of thirteen, and then as a ‘coachman (domestic)’ in 1911, however his whereabouts after this date are unknown and so far no death record has been identified. Fortunately, more is known about Jack and Fred’s younger siblings, including their brother Harry (my great-grandfather, to whom we will return shortly), and their sister Edith Ellen Mills, better known as ‘Nell’, thanks to the research of one of her descendants.

Nell was born on 8 February 1891 in Kegworth, and by the time she was twenty had begun work as a machinist specialised in skirt making, possibly at the same lace factory as her brother Jack. The census of 1911, taken on 2 April that year, records her living at her parents’ house on London Road, however just ten days later she was married at Long Eaton Register Office to an iron pipe jointer named Samuel John Terry (b. 12 March 1886, Bolton, Lancashire – d. 8 August 1966, Boultham Park House, Lincoln, Lincolnshire). Her brother Harry was one of the witnesses. The wedding’s timing and non-religious setting is noteworthy as by the time they were married Nell was five months pregnant with their first child. The photograph below, purportedly taken around this time, shows Nell with her pregnancy concealed discretely behind a well-positioned gate.

Shortly after the birth of their daughter, who they named Ellen (b. 13 August 1911, Kegworth, Leicestershire – d. 18 April 1985, Denny, Stirlingshire), Samuel accepted a job as a pipe jointer at a London waterworks, and the family relocated to the capital. During this period Nell ran a lodging house for navvies at 26 Dock Street, North Woolwich, which was said to have been very difficult as by this time the family had grown to include their second daughter Isabella (b. 7 June 1913, North Woolwich, Essex- d. 12 Apr 2013, Kings Mill Hospital, Sutton In Ashfield, Nottinghamshire), later known as “Cis”.

Soon afterwards the family returned to the East Midlands, settling in Lincoln where they had five more children:

- Frances Anne (b. 28 December 1914, Lincoln, Lincolnshire – d. September 1987, Lincoln, Lincolnshire)

- Kathleen (b. 7 June 1917, Lincoln, Lincolnshire – d. 28 December 1995, Lincoln, Lincolnshire)

- John “Jack” (b. 23 November 1918, Lincoln, Lincolnshire – d. 29 December 1984, Lincoln, Lincolnshire)

- Bessie (b. c. November 1920, Lincoln, Lincolnshire – d. 16 March 1929, Lincoln, Lincolnshire)

- Colin (b. August 1933, Lincoln, Lincolnshire – d. 23 March 1935, Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England)

Samuel, Nell and their children appear to have remained in Lincoln for the rest of their lives, however they changed address a number of times. Their first home in 1914 was at 14 Gaunt Street, and later they are known to have lived at 7 Water Lane in around 1925, at 17 Albany Street in 1939, and finally at 51 Holly Street in about 1958 after Nell suffered a stroke. She died a few years later on 27 April 1960 at the age of sixty nine and was buried at All Saints Churchyard, Bracebridge. Her husband Samuel died aged eighty in 1966.

Comparatively less is known about Nell’s three younger sisters. Alice (b. 12 March 1893, Kegworth Leicestershire) was recorded as a glove maker in the 1911 census, and seven years later she married Thomas Alfred “Alvy” Wilmott, a twenty seven year old labourer (and later fruit and potato salesman) from Sawley in Derbyshire. The couple do not appear to have had any children, but are shown living with Alice’s elderly father George in the 1939 register when they were living at 220 Tamworth Road, Long Eaton. The photograph below of Alvy and George was probably taken in their back garden at around this time. Alice died in Long Eaton on 3 February 1961 at the age of sixty seven, at which time her effects were valued at £312 16s 4d. Her husband Alvy lived a further twenty three years before passing away in 1984 at the age of ninety three.

Even less is known of Frances Harriet Mills (b. 22 April 1895, Kegworth, Leicestershire). Like Nell, as a teenager she she was recorded in the 1911 census as a machinist (skirt maker). She is known to have been married twice, first to a transport foreman named Samuel Hardy Tyers, then later to a man with the frustratingly untraceable name of John H. Smith whose occupation is uncertain. She was thirty three at the time of her first marriage on 14 July 1928, which was three years older than her husband Samuel. In the 1939 register the couple were recorded living at 16 Hawthorne Avenue, Long Eaton, which would have been about ten minutes away from her older sister Alice’s house on Tamworth Road. On 27 November 1943 Samuel died at the age of forty five, leaving Frances a widow at just forty eight. Ten years later though she was remarried to her second husband John H. Smith, and she would go on to live a further thirty nine years. Her death was registered at Ilkeston in the first quarter of 1982 when she was eighty seven. She is not believed to have had any children from either marriage.

The youngest daughter of George and Fanny Mills youngest, Elizabeth Ann “Lizzie” (b. 9 December 1899, Kegworth, Leicestershire) was only eleven at the time of the 1911 census so any jobs she may have held prior to getting married are unrecorded. Given her older sisters’ occupations it is possible she could have worked as a machinist or at the local glove factory on Pleasant Place. Like Alice, she married relatively late in life at age thirty five to George Frederick Steel, with whom she had one son, Richard David (b. c. August 1937, Derbyshire). It is unclear how the family supported themselves, but they are said to have lived above a branch of Boots in Nottingham, which her probate record conforms was at 71A Bracebridge Drive. An unusual story about Lizzie which has been been passed down to some family members was that she believed the stairs in her home were haunted, having experienced a ‘presence’ walk past her and ask the question “what troublest thou?” She died on 8 January 1979 at the age of seventy nine, and her effects were valued at £1,943.

* * *

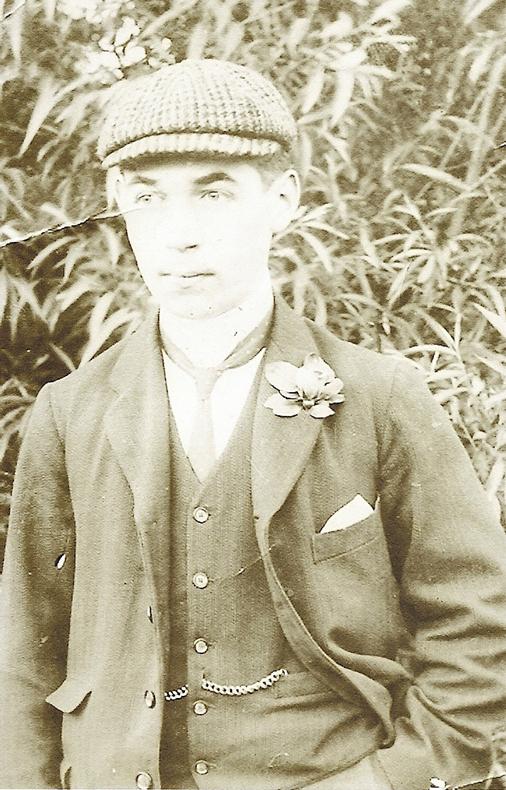

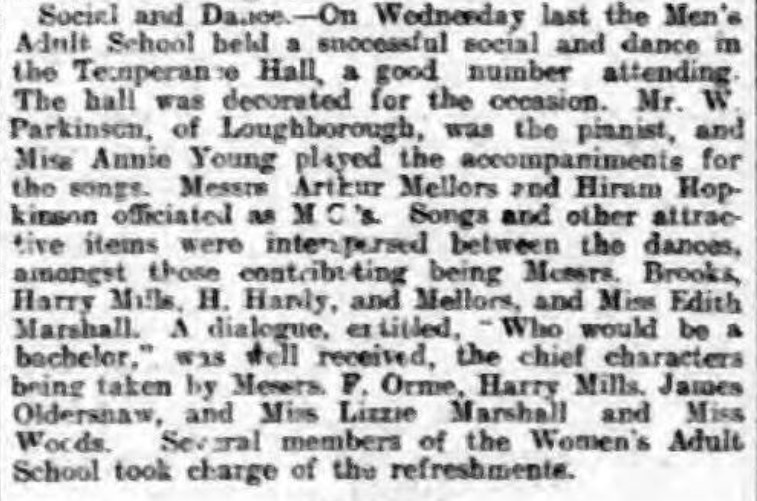

We return now at last to Harry, the third son of George and Fanny Mills and my great-grandfather, born on 7 October 1889 in Kegworth. As a boy he was taken on as a cobbler’s apprentice, and by the time he was twenty one he was recorded working as a ‘boot repairer’ in the census of 1911. That same year he featured in a local news report on a ‘social and dance’ at Kegworth Temperance Hall, at which he performed in a play called ‘Who’d be a bachelor’.

At some point between April 1911 and March 1913 Harry moved to Derby in the hope of setting up his own business. Although his first known address there was at 95 Gerard Street, by 1915 he was running a bootmaker’s shop at 117 Abbey Street. Bootmaking is a related but distinct trade to cobbling (boot and shoe repair), and it is notable that even at this early stage Harry was showing signs of an enterprising, ambitious streak that would serve him well in the years to come.

Shortly after moving to Derby, Harry had met met a young woman named Ruth Spencer (b. c. February 1895, Greatford, Lincolnshire – d. 20 December 1926, 47 Ryhall Road, Stamford, Lincolnshire). Ruth was the daughter of a platelayer and had grown up in Greatford Gatehouse by the railway lines in a small village in Lincolnshire. Coincidentally or otherwise, by 1911 Ruth was working as a domestic servant at 123 Osmaston Street in the house of Charles Trubshaw, a renowned architect with her father’s employer the Midland Railway Company. It is not clear how Harry and Ruth met but they were married on 23 March 1913 in Christ Church, when they were twenty three and eighteen respectively, and soon afterwards moved in together above Harry’s shop on Abbey Street.

A few months later Ruth became pregnant with twins, who they named Mary and Kathleen, however both died shortly after they were born in early 1914. They tried again for a child the following year, and this time the baby survived. They named their first son George Kenneth Mills (b. 28 September 1915, Derby, Derbyshire – d. 17 1980, Wellington, New Zealand), perhaps after his grandfather. Four years later Ruth gave birth to his little sister Julia Mary Mills (b. 24 July 1914, Derby, Derbyshire – d. 19 September 1993, Derbyshire Royal Infirmary, Derby, Derbyshire), known as Mary in later life, who was my maternal grandmother.

Given Harry’s youth and non-reserved occupation it is curious how he was never conscripted for service in World War I, although exemption on the grounds of a health condition is a possibility. Whatever the reason his business clearly benefitted from the relative lack of competition during the war, as the 1925 edition of Kelly’s Directory shows that by then the family were operating at two premises on Abbey Street, a boot repair shop at number 8 and a wardrobe dealership in Ruth’s name at 117. This picture is backed up by their daughter Mary’s account of her childhood written seventy years later, in which she states that Harry employed one man in the bootmaker’s shop and that the other shop dealt in “[second] hand furniture, kitchenware etc.,”and later expanded into antiques.

At this time the family were not poor but neither were they especially well-off. They lived in a simple terraced house, kept a pig in their back garden and the children received nuts, an orange and a shined-up penny for Christmas. According to Mary, her father Harry, a small balding, bespectacled man, was hard-working but emotionally distant. Ruth was the polar opposite: warm, affectionate and attractive, with the distinctive auburn hair which Mary would pass on to her own daughters. As for her older brother, Mary idolised Ken and used to follow him around wherever he went, but it seems Ken occasionally exploited his sister’s unwavering loyalty for his own amusement. One of Mary’s earliest memories is of throwing a silver coffee pot and jug out of a bedroom window at age four because Ken told her to, and on another occasion he apparently made her dig a hole in the garden and bury her teddy bear in it.

An interesting news story from around this time reveals that despite Mary’s angelic view of her mother, Ruth was actually charged with larceny on 8 August 1920 after finding two rings in Belper River Gardens and “making no reasonable attempt to find the owner or acquaint the caretaker of the premises.” Ruth explained that she had intended to keep them until they were advertised for and “had not thought to mention the finding of the rings, or leave her name and address at the gardens.” The Bench fined her £7 10s., stating that there had been no obligation to go to the police but there might have been a risk of prosecution once she was found out.

Ruth’s true intentions that day can never be known, but the story’s publication must have been hugely embarrassing for both her and Harry and could only have contributed to what was by then already a strained relationship. The aforementioned 1925 edition of Kelly’s Directory, which gives Harry and Ruth’s business address as 117 Abbey Street, must have been compiled several years earlier as by 1925 they were no longer living together. According to Mary they had separated when she was about four, which would place the date at around 1922. Of her parents’ separation Mary wrote:

I was too small to wonder…what had caused the break-up of my parents’ marriage. I just remember that I was not really surprised to be in the position I was.

She later came to believe her mother had been involved in an affair, though there is of course no way of verifying this, and her parents’ separation could just as easily have been caused by their seemingly incompatible personalities. It was agreed that Ken would stay with Harry at Abbey Street and Mary would go with Ruth.

Mary and Ruth stayed with a friend named Emma Taylor (known as Aunty Pem) in Sheffield for a few weeks before moving in with Ruth’s sister Annie and brother-in law George Johnson at 47 Ryhall Road in Stamford. Mary lived here with her aunt, uncle and older cousins Reg, Cecil and Mabel, while her mother went to work in a hotel in London. She later recalled her time at Ryhall Road as “a tiny corner of my childhood that was happy” as her adopted family were very loving and treated her well, but we will return to Mary’s maternal family in a future post.

Among Mary’s fondest memories from this time included being crowned May Queen at a carnival in Stamford (an experience ruined somewhat when some jealous girls started chanting “May Queen margarine!”), and playing in her front garden with her school friend Vera Holmes.

The little front garden…was once a place of magic to me, lined down one side with Canterbury Bells all those years ago…we used the bells of the flowers for fairies hats or dolls hats – and I have a distinct feeling that we were probably forbidden to pluck them, thus making the game even more enjoyable. Even so, I was not disobedient with intent! I merely was the sort of child that got carried away with my imagination.

At school Mary was a bright, sporty pupil with a particular love of drawing, reading and writing stories, and she recalled first learning how to form letters by tracing them with her finger in a sand tray. Around this age she also acquired her first (and least favourite!) nickname, ‘Mary Pom-Pom,’ after coming to school wearing a hat with a pom-pom decoration on top.

This happy period was to be cut tragically short however when her mother Ruth fell ill with cervical cancer. Mary recalled a painful conversation shortly before Christmas 1926 with her mother, who had been forced to leave her job due to her declining health and had returned to her sister’s family at Ryhall Road:

I walked into the room and found her crying, and when I asked her why she said “I’m crying because I haven’t a penny to give to you” and I hastily and honestly tried to comfort her by saying “I was only trying to cheer you up!” which was so true that I was distressed that she thought I wanted any money [sic]. It must have been about this time that I said “when you are better mum” we will do something or other, and she said quite calmly and unemotionally that she would never get better as she had something very wrong with her tummy, so possibly preparing me for what was to come a few weeks later.

Ruth died on the twentieth of December 1926 at the age thirty two at Ryhall Road. Her sister Annie was present at the death, and also acted as the informant. She was buried in an un-purchased grave in the non-conformist section of Stamford Cemetery three days later.

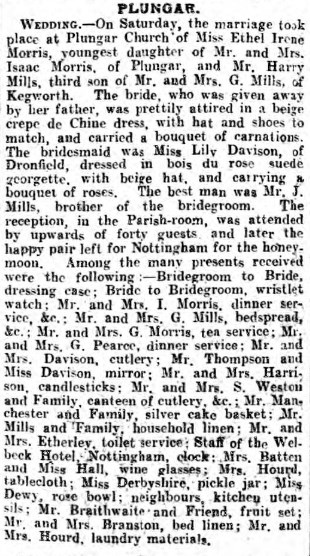

After her mother’s death Mary left Stamford and moved in to 40 Heskey Street, Nottingham with her father and brother. She had been estranged from Harry and Ken since she was four so readjusting to this new home must have been hard enough, but to make matters worse her relationship with Harry’s second wife Ethel Irene Morris was to prove an enduringly difficult one. “Aunt” Ethel, a farm labourer’s daughter from Plungar in Leicestershire, was twenty five when she married Harry Mills on 2 June 1928, thirteen years younger than him and thirteen years older than Mary. Ethel seemed to resent Mary’s presence in the home, perhaps because she served as a reminder of Harry’s first wife Ruth, but whatever the reason she treated her more like a servant than a daughter. In stark contrast to her brother Ken who was indulged as the favourite, Mary was only ever seen as a source of cheap labour, and even after winning a scholarship at school she was forbidden from furthering her education because she was a girl. Perhaps the cruellest thing Mary was forced to endure was when Ethel burned all her pictures of her mother, and to this day it is unknown whether any photographs of Ruth Spencer survive.

Given this combination of Ethel’s vindictiveness and her father’s apparent complicity or indifference, it is not surprising that Mary left home as soon as soon as she was able at around the age of seventeen. After securing her first job at I.R. Morely’s hosiery factory in Heanor, Derbyshire, she began lodging in the home of her friend and co-worker Hilda Hunter, with whom she would remain close for the rest of her life. On hearing of Mary’s death many years later Hilda wrote a letter of condolence to one of her daughters in which she gave a vivid account of her and Mary’s work and life during this period. Their hours at the factory were “7.30 AM – 1 PM, 2 PM – 5.30 & Sat AM. No tea or coffee breaks & until I was 16 I earned from 10/- – 12/- a wk” (around £20 in today’s money).

We used to go to the pictures – “the Cosy” [Heanor’s Cosy Market] & the Empire…& when we went dancing to the Town Hall in Heanor at the interval Mary & I would rush over to Elliot’s chip shop in Ray St. for tripe – but Mary only ate the crinkled bits so I had all the thick pieces. We occasionally went dancing at Annesley, & Mary would say “leave it to me I’ll get us a lift home,” & she did, you wouldn’t dare do it today. She was a happy person with a laughing smile.

It was said that when she went out dancing Mary was pretty enough to “fetch a duck off water,” and the impression one gets from Hilda’s account and contemporary photographs is that for the first time in almost a decade Mary was truly happy. She was financially independent with an active social life and a good circle of friends, but by far the most significant relationship she would go on to develop during this period was yet to come.

The life and family history of my maternal grandfather Frederick England has been discussed elsewhere in this blog (see There’ll always be an England (part 3)). He was born on 23 July 1912 to a Heanor coal miner named Thomas and his wife Maud Ling. His father’s family had lived in Derbyshire for generations, were strongly connected to the area’s major extractive and manufacturing industries and had been active in local politics. His mother’s family by contrast were geographically dispersed and made their living mainly from general dealing and traveling fairgrounds (see Travelling with the Lings (part 4)). From this unlikely union came Fred, who worked as a silk hose finisher at I.R. Morley but was also a talented gymnast with ambitions of becoming a professional. Given that he and Mary worked in the same factory and his best friend at the time was Hilda Hunter’s brother it was perhaps inevitable that their paths would cross at some point. During their courtship they would go to dances together and on one occasion went on a cycling holiday to the seaside on a tandem (although apparently Mary left all the pedalling to Fred). At some point around Christmas 1937 however, Mary became pregnant with Fred’s child, and a few months later they were married in Heanor on 16 April 1938. In recognition of her four-month-old baby bump Mary wore a white dress with a subtle hint of apple, and a Juliet cap beaded with pearls.

Following the wedding Mary and Fred moved in with Fred’s parents at 98 Holbrook Street, Heanor. Shortly after Mary gave birth to their daughter Gillian Maureen England on 23 September 1938 they found a house to rent across the road at number 119.

Had Gillian been born at almost any other point during the twentieth century she could have expected to have been followed within a year or two by a younger brother or sister, but of course just under a year after she was born Britain declared war on Germany, and any hopes Mary and Fred may have had of settling down and having more children were quickly dashed. Among his five brothers Fred was the only one at this point to have started a family, but unfortunately he was also the only one of fighting age working in a non-protected industry and was drafted into military service in 1940. He joined the local tank regiment the 9th Lancers as a trooper and after training was sent to Egypt as part of the 1st Armoured Division in General Montgomery’s famous 8th Army.

While Fred was away fighting, Mary was left to raise their one year old daughter Gillian by herself. Thanks to Fred’s large extended family though she had a strong support network, and during the height of the blitz she even welcomed several evacuees into her home at the age of only twenty two (after they had been thoroughly de-loused of course). Local businesses like I.R. Morley were adapted to manufacturing parachutes for the war effort but the lack of heavy industry in the Heanor area meant the threat of German air raids was relatively low (aside from the odd stray bomb on its way to Derby’s Rolls Royce factory where Fred’s brother Ken worked). Despite her husband’s absence Mary’s memories of the war years would be largely happy ones of her and Gillian surrounded by loved ones, who were brought closer together through their shared struggle.

This neighbourly spirit even led to a brief reconciliation with her father Harry, who by this point was running the Greendale Oak inn in Cuckney, Nottinghamshire, and whose business was booming by 1944 thanks to the large number of American G.I.s stationed nearby. Harry was first recorded as a publican at the Coach & Horses in Billinghay in the 1939 register (which also mentioned that he was a sergeant, perhaps in the Home Guard), and by 16 February 1940 he had been promoted to manager of the Hurt Arms in Ambergate, which was owned by the same brewer. By all accounts he was a very shrewd businessman. His sister Nell even recalled visiting him with her family at the Greendale Oak during the War and being rather affronted when Harry asked them to pay for their drinks. His ascent up the social ladder is evident from his membership of the the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes fraternal society, for whom he was reported to be the “Retiring Provincial Grand Primo for South Lincolshire” (Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 6 January 1940). Later in life he was also said to have been a member of the Freemasons.

After the war there was to be no easy return to the way things had been for Fred and Mary. Fred, shell-shocked by his experiences struggled to readjust to civilian life, and for Mary there would remain a sense that the gentle man she had fallen in love with had been brutalised, as Mary’s friend Hilda wrote many years later:

I remember your mum saying Fred wasn’t the fellow you knew after the war – but it changed all the young men, they went through so much, & to our generation it is still in our minds.

Their relationship would gradually recover over the next twelve months, and 1946 was to be a pivotal year for them in more ways than one. Not only did it see the birth to their second daughter, but a few months after this they were granted a mortgage loan of £700 for their house at 119 Holbrook Street. The approval of this loan, worth around £18,165 in today’s money, is the first indication of Mary and Fred’s steadily improving financial situation during the late forties and fifties. After the war Fred had intended to retrain as a P.E. teacher, however he instead took a job as a dyer at Aristoc, another hosiery manufacturer based in Langley. After a time he was promoted to foreman and eventually gained managerial position which paid well enough to enable the family to move into a larger detached house at 34 Crosshill in Codnor, Derbyshire. Their new house was purchased on 16 May 1959 for the cost of £2000, about £30,000 in today’s money, and both Mary and Fred would remain here for the rest of their lives.

As was common among women of her generation, Mary had left work after getting married to become a full-time mother (her third daughter having arrived in June 1953). Like Ruth before her, Mary is remembered as being a very affectionate, loving mother who always put her children first. Perhaps as a result of her father and step-mother’s dismissive attitude to her own education, she always encouraged her daughters to work hard at school and pursue fulfilling careers. In time her three daughters would grow into assertive, confident, professional young women. Seeing her daughters leave home and establish careers would in turn encourage Mary to re-enter the world of work. Aside from a brief stint working as a meal supervisor at Loscoe Road Infants’ School Mary had not been in paid employment since giving birth to Gillian in 1938, but after attending a number of Red Cross classes she decided to retrain as an occupational nurse. In about 1966 she took an industrial nursing course at Nottingham General Hospital before going on to work as a factory nurse at Burnham spring works and Tinsley Wire Ltd. until her retirement in around 1974.

The mid-to-late sixties was to be a period of significant change for Mary both professionally and personally. Not only was she establishing a career for herself for the first time in thirty years, but she was also starting to rekindle a relationship with her estranged family. It began in 1963 with a visit from her brother Ken, who after serving as an army cook in the war had emigrated to New Zealand and started a family of his own. During the visit he convinced Mary that if she did not make peace with their father now, she might never get the chance again as by this point Harry was already in his seventies.

Mary and her father had never been close, but following an argument between Harry and Fred in around 1952 they had not spoken in more than a decade by the time of Ken’s visit. At Ken’s prompting therefore, Mary took Fred and her two youngest daughters to the Station Hotel in Worksop which Harry and Ethel were running at the time, and from that point onwards she did manage to maintain a civil relationship of sorts with her father. Even when Harry and Ethel lost most of their money from their hotel business in the mid-sixties, Fred and Mary graciously helped re-home them in a terraced house in Heanor. Harry died in early 1968, and Ethel on 19 November 1981. Although Mary had been the one to rehouse her and even arrange her funeral, the entirety of Ethel’s £20,015 inheritance passed to her brother Ken.

Since retiring together in 1974 Mary and Fred had been enjoying their free time together, finally unencumbered by work or child-caring responsibilities. That was all to change quite unexpectedly one day when Fred was crossing the road on the way back from the local garage and was struck by a severe heart attack. He died on 24 September 1980 at the age of only sixty eight. The sudden loss of her husband deeply affected Mary, and for at least two years she was quite inconsolable. It was only the birth of her third granddaughter in 1982 which eventually brought her out of this depression and provided her with a renewed sense of purpose. In her later years she also felt more free to develop her own opinions and interests, and there is no question that Mary became a far more independent and assertive woman than she had been in her youth. For example, ever since Fred had become a manager at Aristoc Mary had voted Conservative in accordance with her husband’s wishes. After Fred died however her views shifted dramatically to the left to the point where she could not see Margaret Thatcher on the television without declaring “if she came up Crosshill I’d kill her,” and she was overjoyed on witnessing Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990. She also rediscovered her love of drawing, painting, gardening and needlework, skills she would enjoy passing on to her grandchildren.

This is the woman I knew growing up. Among my earliest and happiest memories are of going to visit my ‘Gaga’ at Crosshill with my family at least once a week, playing in the garden or sitting in the big armchair with her learning how to paint. She was always smiling and laughing and was never stern in the least. Even in her final days, when I visited her in the hospital and remarked that her respirator mask made her look like an elephant she seemed to find this greatly amusing. Sadly Mary would spend the greater part of her final years in and out of hospital owing to various illnesses. She eventually died in Derby Hospital on 19 September 1993 at the age of seventy five. The huge collection of heartfelt commemoration cards which have survived stand as testament to the number of lives she touched over the years. Although not a believer in an afterlife herself, I think she would definitely have appreciated the following words from my mother’s friend:

I’m sure she’ll be alright…I bet right now she’s fluttering her eyelashes & looking for a big pan to make everyone some piccalilli!!

Today her descendants include her two youngest daughters, plus four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren, and her brother Ken has living descendants in New Zealand. On 29 July he had married Marjorie Bradshaw in Billinghay, with whom he had one daughter. They appear to have lived at various places including Christchurch and Wellington up to the 1970s and he died on 17 March 1980. Members of the wider Mills family can be found all over the UK and beyond, and several have been generous enough to provide me with images and anecdotes for this blog. In the next series of posts I will be looking at the ancestry of Mary’s mother, Ruth.

Sources

Mason, Sheila A. “Black Lead and Bleaching: The Nottingham Lace Industry.” BBC website. Accessed 20 March 2019. http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/work/england/nottingham/article_2.shtml.

Russell, Dave. Popular Music in England, 1840-1914: A Social History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.