This is the second of two posts on the family history of Ruth Spencer, the mother of my maternal grandmother Julia Mary Mills, and will focus specifically on her parents and siblings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For the first part of the family’s story see Spencer Tracing (part 1).

* * *

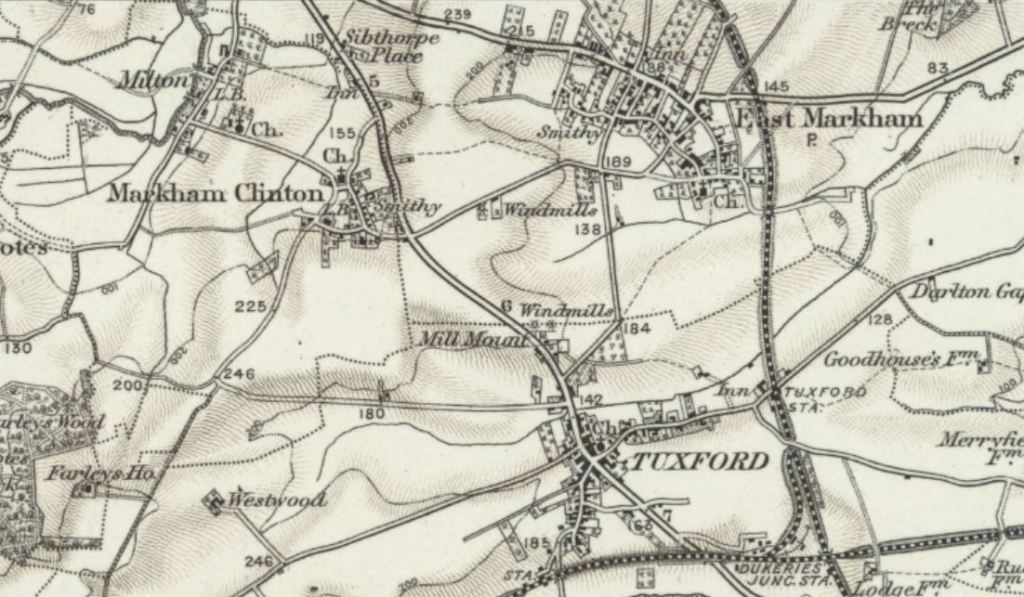

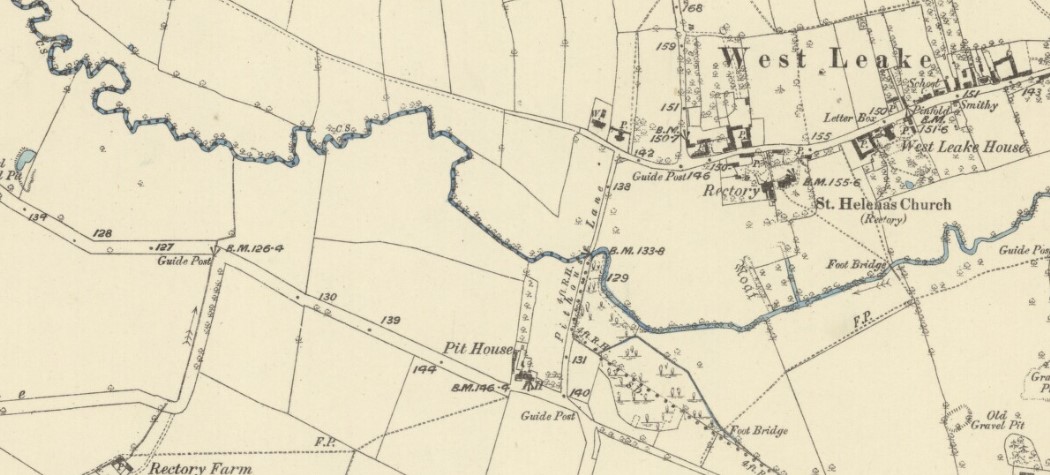

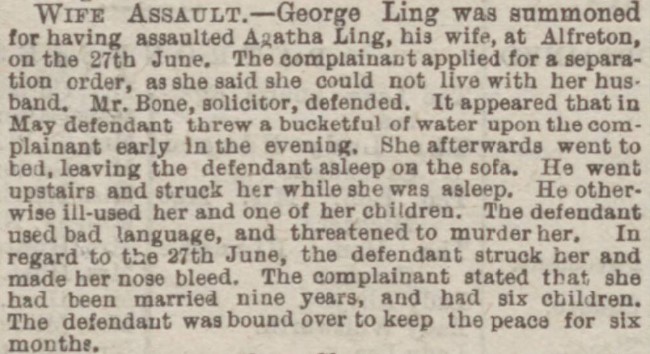

Ruth Spencer’s father George was born and raised in the hamlet of Milton in Nottinghamshire. He had been baptised on 16 June 1850 in nearby West Markham, and his formative years were marked by a series of premature family deaths. At the age of five he lost his older sister Anne, whose death was followed by that of his little brother William when he was fourteen, and then his father George Sr. three years later. At some point between 1865 and 1871 he moved with his mother Elizabeth and two surviving sisters to East Markham, where he helped out on his mother’s farm at 9 Low Street.

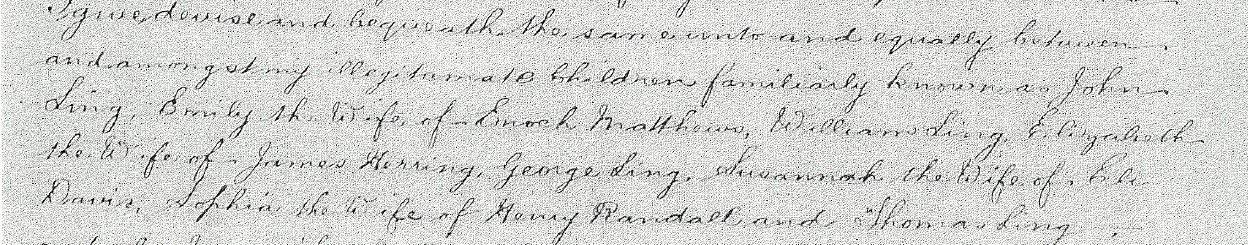

In his early twenties George met a young woman from Lincolnshire named Emma Staples, with whom he would go on to marry and have seven children, including my great-grandmother Ruth. Emma had been born in Canwick on 15 April 1850, however the name Staples does not appear on either her birth certificate or baptism record. Her parents were John Gant (bp. 8 January 1827 Metheringham, Lincolnshire – d. 24 March 1881, Metheringham, Lincolnshire), a joiner, and a servant named Elizabeth Carter (24 December 1822, Canwick, Lincolnshire – bur. 17 January 1895, Harmston, Lincolnshire), who were unmarried but their daughter was nonetheless christened ‘Emma Gant’ on 21 September 1850. Unusually for a child of unmarried parents her father was named in the parish register.

Officially however, her birth was registered under the name ‘Emma Gant Carter’, and by 1851 she had dropped her father’s surname entirely and was going simply by ‘Emma Carter’. That year she was living in Canwick with her maternal grandparents, her mother Elizabeth, an uncle Henry, and her older sister Alice (a daughter of Elizabeth’s from a previous relationship). By the next census in 1861 she had adopted the surname of her step-father Joseph Staples, an agricultural worker from Waddington who her mother had married on 13 June 1854. Shortly before her own marriage, Emma was recorded in the 1871 census working as servant for a farmer named William Twidale in Scampton.

She and George were married in East Markham on 24 October 1873. They were both twenty three and George’s sister Mary was one of their witnesses. Emma was by this time almost eight months pregnant with their first child Joseph Henry Spencer, who was born on 8 December in Harmston, Lincolnshire, where a number of Emma’s relatives were living at the time. Given the closeness of his birth date to George and Emma’s marriage it is plausible that Emma briefly moved back to Lincolnshire after the wedding to conceal how far along her pregnancy was from George’s family. If true, this could explain why Joseph was not baptised until 24 April 1874, more than four months after he was born.

Over the next decade George and Emma went on to have four more children in East Markham, whose names were:

- George (b. 17 May 1975, East Markham, Lincolnshire – d. 7 February 1963, Stamford, Lincolnshire)

- Elizabeth (bp. 29 October 1876, East Markham, Lincolnshire)

- Julia (b. 30 March 1878, East Markham, Lincolnshire – d. c. May 1945, Peterborough, Huntingdonshire)

- Annie (bp. 25 April 1881, East Markham, Lincolnshire)

From their baptism records it is possible to trace their father George’s career throughout the 1870s. At the time of his marriage in 1873 he was recorded as a railway labourer, however a few months later in early 1874 he described himself as a farmer in his son Joseph’s baptism record. He continued to give this as his main occupation until 1881, after which he is consistently recorded as a railway platelayer, a job he appears to have held for the rest of his life. As a platelayer his work would have involved both laying tracks and patrolling, inspecting and maintaining the lines. They were often based in wooden ‘platelayers’ huts’ at the side of the railway, as can be seen in the photograph below showing a gang of Scottish platelayers at Blackford.

While George appears to have identified primarily as a farmer until 1881, we know he had been working concurrently as a platelayer since at least 1875 from a story in the national press. The article in question describes an extraordinary incident from his working life which came very close to killing him. According to the story, on 1 June 1875 he and three other employees of the Great Northern Railway Company, George Jackson, George Featherstone and their foreman William Freeman, set off to work on the railway line between East Markham and Tuxford at about seven o’clock in the morning. A few hours later they found “a large number of beans, used, it is said, in the production of castor oil” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 7 June 1875) which they set about eating. By midday they felt so sick they were forced to stop work, and their two-mile walk home took them until five o’clock in the evening. It is now known that castor beans contain ricin, one of the most toxic substances found in nature, which has been used in biological warfare and whose symptoms include fever, vomiting, diarrhoea and eventually life-threatening organ failure. George was lucky enough to survive the poisoning, however his co-worker George Jackson was not so fortunate and died three days later.

The 1881 census recorded the family living at York Yard in East Markham, minus their eldest son Joseph who was staying with his maternal grandparents in Harmston. In 1883 however they relocated to the village of Greatford in Lincolnshire, where they had two more children:

- Thomas (b. c. May 1889, Greatford, Lincolnshire – d. 4 November 1897, Greatford, Lincolnshire)

- Ruth (b. c. February 1895, Greatford, Lincolnshire – d. 20 December 1926, 47 Ryhall Road, Stamford, Lincolnshire)

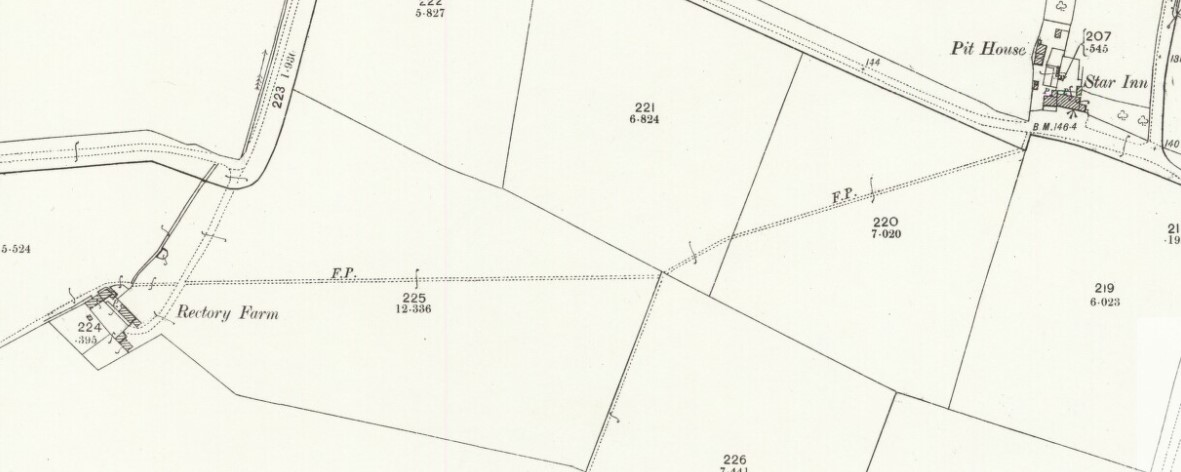

The building in which they took up residence was known as ‘Greatford Gatehouse’, and was located at the level crossing on the western edge of the village. This would have served as both the Spencers’ family home and George’s base of operations for his work as a platelayer. The house has long-since been demolished but the photograph below shows Greatford crossing in around the mid-1960s with the gatehouse visible on the right. Its location can also be identified on contemporary Ordnance Survey maps.

By 1891 George and Emma’s eldest son Joseph and eldest daughter Elizabeth had both left home. Their second son George was employed as an agricultural labourer at age fifteen, and all their younger children except John Thomas were at school. After the birth of their last child Ruth however, tragedy struck the family once again on the afternoon of 4 November 1897. While racing home from school with a group of friends, George and Emma’s youngest son John Thomas Spencer was struck down and killed by a train at the level crossing outside the gatehouse where he had lived all his life. He was eight years old. According to a witness, “the top of his skull was cut off and his brains were scattered about the line” (The Grantham Journal, 13 November 1897, p. 6, cols. 3-4), and his father George had the awful task of identifying his body. At a subsequent inquest at the Hare and Hounds public house questions were raised over whether the signalman on duty should be held responsible for failing to lock the gate before the train passed. The signalman explained however that he had not seen the children approaching as they were concealed from view behind a tall hedge, and in the end a verdict of accidental death was returned.

Unfortunately John Thomas’s premature death would not be the last to befall the family in the years surrounding the turn of the century. By the 1901 census all of George and Emma’s surviving children except Ruth had left home, however they had been joined by Emma’s nineteen year old niece Florence Pottage. Sadly this was to be the last census on which Emma would appear, as two years later on 5 December 1903 she passed away at the age of fifty three. Her youngest daughter Ruth would have been only eight at the time, coincidently the same age Ruth’s daughter Mary was when she lost her mother twenty three years later.

Two years later, George was married for a second time to a domestic nurse named Betsy Stanniland (b. 20 January 1865, East Markham, Nottinghamshire – d. 21 March 1965, Stamford, Lincolnshire). It is uncertain how the couple met but as Betsy came from East Markham near where George grew up it is possible they were family friends. They were living together at Greatford Gatehouse at the time of the 1911 census, which also recorded that George had switched employers and was now working for the Great Midland Railway Company. In his daughter Ruth’s marriage certificate from 1913 his occupation is given as ‘foreman platelayer’ suggesting he had secured a promotion in the intervening years, although he was also named as a foreman in the report on his son’s death sixteen years earlier. That same year he appeared again in the local press, but fortunately the reason was far less serious this time, having been given a 1 shilling fine for riding without reins at Uffington (The Grantham Journal, 3 May 1913, p. 5, col. 2). George died at the age of sixty nine on 9 December 1919 and was buried in St. Thomas Beckett churchyard in Greatford. His effects valued at £752 6s. 5d. went to his widow Betsy, who went on to live a further forty six years but never remarried. She finally passed away in 1965 in her hundredth year.

* * *

The surviving children of George and Emma Spencer went into a variety of occupations, many of which were connected to the railways. Their eldest, Joseph Henry Spencer had been a ‘railway telegraph lad’ at the age of eighteen, when he was lodging at 43 Frenchgate in the house of a grocer named Sarah Tinson. Ten years later he was recorded in the 1901 census at 28 Haddon Place in Burley, Leeds, working as a railway telegraphist. Electrical telegraphy had been used by British railway companies since 1846, and telegraphists like Joseph were responsible for to communicating messages across the transport network via morse code. It was skilled and relatively high paying work and could be considered one of the first high-tech occupations.

The same census also showed Joseph living with his wife Hannah Maria (née Hirst), with whom he had been married for two years. They had one son, Tom, in 1909 before Hannah’s death in 1922. Joseph was married again on 29 September 1924 to Hannah Elizabeth Louth, by which time he was employed as a railway clerk. His marriage certificate also shows he had moved to 29 Haddon Place by then, where he lived until his death on 7 September 1950. His will was proved on 9 November, and his effects were valued at £752 13s.

George and Emma’s second son, who like his father and grandfather before him was also named George Spencer, had worked as an agricultural labourer in his teens. After leaving Greatford he found employment as a foundry worker in East Retford, where he lived as a boarder at 34 West Street. By 1911 he had moved in with his sister Annie’s family at Belmesthorpe in Rutland, and was once again working as an agricultural labourer. At some point during the next four years however George moved back in with his father and step-mother at Greatford Gatehouse, and it was while living here that he enlisted for military service on 25 November 1915. His World War I service record attests that he was already forty years old when he signed up, and was 5’5″ tall.

George was initially assigned the rank of private in the Lincolnshire Regiment on 5 April 1916, but was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment five days later. Perhaps on account of his age, on 29 April he was deployed as a non-combatant in the regiment’s Labour Company A, and became part of the Labour Corps after it was formed on 11-12 May 1917. Details of his service are sketchy, but we know he was deployed on the Western Front and his duties would have involved essential manual work like digging trenches and repairing roads throughout key campaigns including the Somme offensive. As the war wound down George was posted to the 507th Agricultural Company on 28 December 1918, which would have been tasked with ensuring the army’s food supply, and he was finally demoblised on 13 March 1919 at the age of forty three.

After returning home, George settled in Stamford close to his sister Annie’s family, with whom my grandmother Mary lived between 1923 and 1926. According to her recollection, George remained a bachelor his whole life, and was known as “a singer of some repute”. Upon finally hearing him sing in church one day however, she remembered being embarrassed by how loud he was. By 1939 he was living at 59 Cemetery Road in the house of a woman named Anna M. Rippon, and was still apparently working as an agricultural labour at the age of sixty four. In his old age he retired to Brownes Hospital almshouses, where he died on 7 February 1963, leaving behind £793 17s in personal effects. He was eighty seven years old.

According to census records, a least three of George’s four younger sisters began their working lives in the domestic service industry. In 1891 the eldest of these sisters Elizabeth was working in the household of a retired farmer from Preston, Rutland, called John Pretty at age fifteen. Three years later she married a Nottinghamshire railway signalman named George Edward Baguley and moved to Pudsey near to her brother Joseph in Leeds. Here she gave birth to her first child in 1898, before moving again to the village of Tyersal between Leeds and Bradford for her second a year later.

In the 1901 census the family were recorded living at Whitehall Lane in the Leeds parish of Drighlington, where their third child had been born the previous year. By 1906 however they had returned to George and Elizabeth’s home county of Nottinghamshire, first settling in Arnold before finally coming back to Elizabeth’s home village of East Markham by 1910. The 1911 census shows they had a further three children in Nottinghamshire and lived on Askham Road. After this it is unclear what happened to Elizabeth, as neither her entry in the 1939 register nor a death certificate have yet been found. Her husband George died on 1 October 1947, leaving behind £285.

Elizabeth’s younger sister Julia Spencer was also employed as a domestic housemaid for a time, and in 1901 was recorded in the service of a William Taylor of Hanbury, Staffordshire. Also like her sister, Julia went on to marry a man worked on the railways, Yorkshire engine driver Thomas Crowe. The couple were wed in Thomas’s home district of Guisborough in 1909 when Julia would have been around thirty one and Thomas forty seven. The following year Elizabeth gave birth to their first child, Thomas Spencer Crowe.

By 1911 the family were living at 25 Oxford Street in Saltburn-by-the-Sea on the Yorkshire coast. They appear to have stayed in the vicinity until at least 1920, and during this time had at least two more sons. Their whereabouts over the next nineteen years are largely unknown, but the 1939 register revealed that Julia had been running a boarding house at 33 Broadway in Peterborough. Her husband Thomas had by then retired, and all their children had left home. Thomas died the following year, and Julia passed away five years later at the age of sixty one.

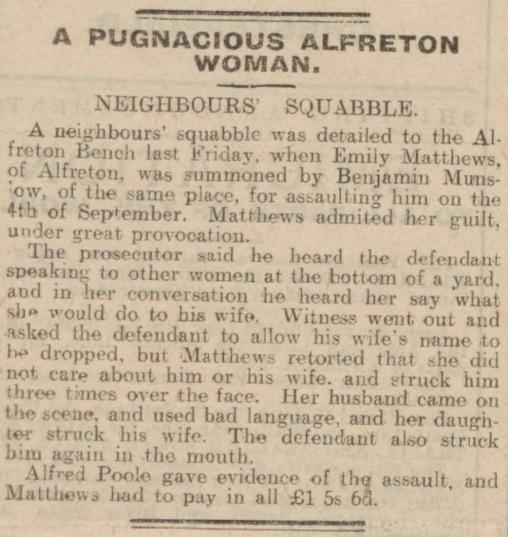

We know rather more about the third Spencer girl, Annie, whose family my grandmother Julia Mary Mills stayed with for several years as a little girl. Continuing a pattern set by her older sisters, in 1899 Annie married a railway worker named George Henry Johnson when she was eighteen and he was twenty four. Prior to their marriage, George (whose name seems inescapable within the Spencer family) had been a railway telegraph lad. According to the staff registers of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway he was then employed by the company as a signalman at South Elmsall, Yorkshire, on 16 June 1897, where he earned a wage of £1 3s per week. Given their shared occupation and geographical proximity it seems entirely plausible that George met Annie through her older brother Joseph at around this time. A later entry in the register reveals that he received a caution in December that year but the reason was not recorded. A final entry states that he was “transferred to G.M” on 19 April 1898. This perhaps stood for ‘Great Midland’, a misnaming of the Great Central Railway which had succeeded the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway a few months earlier.

Shortly after their marriage, Annie moved with George to Ryhall in Rutland, a short distance from Greatford, where she gave birth to her first son Cecil Henry Johnson on 17 June 1900. The following year the census recorded the three of them living together in a house on Main Street, however within a year they had relocated to the nearby hamlet Belmesthorpe. Here they had two more children named Reginald Edgar (b. c. August 1902) and Constance Mabel Johnson (b. 8 December 1903), and by 1911 Annie’s unmarried older brother George had also joined them in the family home.

Meanwhile, many miles away in Derby, George and Annie’s sixteen-year old younger sister Ruth Spencer was working as a domestic servant for the railway architect Charles Trubshaw at 123 Osmaston Street. This building was later absorbed by the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary, which may explain why her daughter believed Ruth had once worked as a cook there. Much of Ruth’s story has already been covered in Going through the Mills (part 5) but to recap the pertinent details, in 1913 she had married a bootmaker named Harry Mills with whom she went on to have two children, George Kenneth (b. 28 September 1915, Derby, Derbyshire – d. c. 1980 New Zealand) and my grandmother Julia Mary Mills (b. 24 July 1918, Derby, Derbyshire – d. 19 September 1993, Derbyshire Royal Infirmary, Derby, Derbyshire). Unfortunately the marriage did not last, and following her separation from Harry Ruth and her daughter Mary went to live with her sister Annie’s family, which is where we re-join them in about 1925.

From my grandmother’s account we know her aunt Annie’s family had moved from Belmesthorpe to 47 Ryhall Lane in Stamford by this time, however her older cousins Cecil and Reginald had already left home. She remembers her aunt as a “staunch Methodist”, and there is evidence to suggest the other Spencer children shared her faith (most notably the absence of Anglican baptism records for their children and the fact that Ruth was buried in the non-conformist section of Stamford Cemetery). Mary also fondly recalled her cousin Mabel, a milliner who made her hats and apparently had “a lump on her back”. Being only young at the time Mary asked her about this, but Mabel apparently did not take offence.

Mary also confirms that her unmarried uncle George Spencer (the “singer of some repute”, who would attempt to surreptitiously give her a penny whenever he came to visit) and aunt Julia (Crowe) were living nearby at the time, and the impression one gets from reading her account is of a close, loving and supportive extended family. Julia appears in the photograph below alongside her sister Annie, her brother-in-law George Henry Johnson and Mary from 1925:

Unfortunately due to the actions of my grandmother’s step-mother this is the only surviving photograph in our family’s possession which features any of the Spencers. After Ruth’s premature death in 1926 (which was registered by her sister Annie) Mary moved in with her father Harry and his new wife, and appears to have lost contact with her mother’s side for several years.

The 1939 register shows her aunt Annie had by then moved to Peterborough, and that her husband George Henry Johnson had sadly died sometime before. The house on Chain Close where she lived was known as ‘Greatford’, a name with great significance to the Spencers and perhaps a reminder of happier times for a woman who had endured more than her share of family tragedies over the years. It is unknown when she died, or what happened to her son Reginald, but her other two children Cecil and Mabel were both living with her in 1939 working as a window cleaner and a shop assistant and dressmaker respectively. The register also records the presence of another woman in the house named Olive A.L. Rigeon, who is said to be Mabel’s partner in a draper’s business. Cecil passed away in 1963, and his will was proved by his sister Mabel, whose own death certificate has yet to be found.

It is known that my grandmother had re-established contact with some of her mother’s family by the mid-1950s, when her two youngest daughters went to meet them in Stamford. She would later revisit her adoptive home on Ryhall Lane shortly before her death in 1993, and in 2011 I was able to identify the unmarked grave in Stamford Cemetery where her mother Ruth had been buried eighty five years before. Sadly in the absence of any photographs, this may now be as close as her descendants can get to a woman whose face we may never see, but my search continues regardless.

* * *

Here ends, for now, the account of my mother’s family history. In the next series, ‘Keeping up with the Joneses’, I will be turning my attention to the Land of My Fathers and my paternal ancestors in Wales.