This is the much-delayed, third and last installment in my series of posts on the Halls, the maternal ancestors of my grandfather Frederick England’s mother Maud Ling. In it I will be focusing on the children of Charles Buxton (1826-1903) and Miriam Hall (1833-1910) of Alfreton, including William, John Samuel, Emma Elizabeth, Rose Ellen, Frederick Charles, George Henry and Alfred Buxton, as well as Maud Ling’s mother Mary Ann Hall. For the history of the Hall and Buxton families up to this point see Halls that echo still parts one and two.

* * *

By the time Charles and Miriam Buxton died in 1903 and 1910 respectively, their surviving children had all established careers and families of their own. Although the Devonshire Arms inn passed out of the family’s hands shortly after Charles’s death (by 1911 it was under the management of Joseph Shearman), a number of his children appear to have followed him into the fish, fruit and grocery trade. The first to do so was his eldest son William Buxton (b. 24 September 1856, Alfreton, Derbyshire), who by 1881 had opened a fruiterer’s shop at 27 King Street, a few minutes up the road from the Devonshire Arms. That year’s census records him living with his wife Eliza (née Bent), with whom he went on to have seven children before her death in 1899. On later censuses William was shown working as a ‘fruit hawker’ in Brampton in 1891, and then at Chesterfield ten years later, where he was living with five of his children at 117 Chatsworth Road.

The dates and locations may be significant here, for as we saw in Travelling with the Lings (part 3), several members of the Ling family were also working as hawkers in Brampton and Chesterfield in those same census years. William would undoubtedly have known the Lings through his older sister Mary Ann, who had married John Ling in 1871, but his proximity to them over such a long period suggests there may have been a history of personal and business connections between the two families which the census only hints at. It is possible this Buxton-Ling relationship predated even John and Mary Ann’s marriage, as John’s father George Ling was an innkeeper and publican based on King Street (see Travelling with the Lings (part 2)), just like Charles Buxton. George and Charles could have been old friends or business contacts who wanted to cement a profitable partnership through the marriage, or perhaps they had been rivals who saw it as a means of ending a feud.

Whatever its origin, it is clear this relationship between the Lings and the Buxtons remained strong over at least two generations. For example, Charles and Miriam’s second son John Samuel Buxton (b. 8 July 1859, Alfreton, Derbyshire) was for a time guardian to one of John and Mary Ann Ling’s daughters (a point I will return to shortly). In addition, Samuel, as he was commonly known, appears to have been cut from similar cloth to his brothers and sisters-in-law on the Ling side, as like them he was no stranger to physical altercations and occasionally found himself in trouble with the authorities.

Aged twenty one he had married a woman from Somercotes named Mary Stanton, and shortly afterwards moved with her to Skegby in north Nottinghamshire where he worked as a coal miner. By the time his first son was born in 1884 however they had moved back to Alfreton and Samuel and was employed as a county court bailiff. That same year he was named in the local press in connection with an illegal raffle which took place at the Queen’s Head inn without the landlord’s knowledge (The Derbyshire Times, 15 October 1884, p. 3, col. 5). A clock belonging to Samuel had been the main prize. A somewhat more serious allegation came the following year when he was charged with making an affray alongside Samuel College of Wessington at Oakerthorpe. Both men were bound over in the sum of £5 to keep the peace for three months (Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal, 26 June 1885, p. 6, col. 6).

As a county court bailiff, charged with recovering debts by forcibly entering people’s homes and seizing their property, Samuel would undoubtedly have had made a few enemies over the years, so violent exchanges like the one described above are hardly surprising. Bailiffs were widely resented by the working classes for whom they represented an iniquitous system which favoured the rich, as Kruse describes in The Victorian Bailiff: Conflict and Change (2012, Preface):

Distress [debt collection through property siezure] was compared to the bastinado used to oppress farmers in the East, an “injurious grievance” which resulted in the cottages of the poor being ransacked. These attacks developed into a full blown campaign for abolition of distress late in the [Nineteenth] century, but the bailiff in all these instances suffered for no fault of his own and was condemned however blameless his actions.

From the story below, taken from the Heanor petty sessions, it is clear Samuel occasionally found himself on the receiving end of this widespread popular anger:

Another story published nine years later reveals Samuel was also accused of “wilful and corrupt perjury” by a local farmer, who alleged that £1 in rent arrears had been wrongfully seized before it was due (The Derbyshire Times, 23 January 1897, p. 3, cols. 3-4). The charges were dropped after five hours’ deliberation, but together with his earlier assault the story clearly illustrates the thankless nature of his work and the hostility he would have faced on an almost daily basis. The engravings below from The Illustrated Police News depict similarly fraught encounters between bailiffs and tenants which would have proved popular with contemporary readers.

Samuel appears to have left his regular employer Messrs W. Watson & Son shortly after this incident, and sued them for £10 2s. 9d. in overdue wages (The Derbyshire Times, 30 April 1898, p. 6, col. 6). The firm issued a counter-claim of £5 18s. 5d., alleging he had been drunk on duty and had left a repossessed house unguarded. A lively scene ensued at Alfreton County Court when upon hearing these allegations Samuel called his accuser a rogue, and said he would rather leave the court than stay and listen to their falsehoods. According to the report, “Buxton was then removed from the Court room to an ante-room, where he was kept until the business had been transacted”. Despite his protestations, a string of witnesses came forward to corroborate the firm’s claims, saying “he was drunk all the time”. The judge let him off with a warning but said he should not have been so foolish as to act in the manner he did, especially as he had been serving as a representative of the court.

It is possible Samuel’s drinking and erratic behaviour had been triggered by his wife Mary’s death two years earlier. There is a record of him auctioning off his household furniture and general effects on 19 September 1896, shortly after relinquishing his property at 27 King Street (The Derbyshire Times, 16 September 1896, p. 2, col. 6), and by the following census in 1901 he had moved back in with his mother and father at the Devonshire Arms. His occupation was recorded as ‘labourer’. Over the following decade however his fortunes appear to have steadily improved, as by 1911 he had married again to a woman named Elizabeth. That year’s census shows them living together with their children at 151 King Street, and records his new occupation as a furniture dealer.

Before moving on to Charles and Miriam Buxton’s other sons and daughters, a few words on Samuel’s children. Although it’s not entirely clear from the censuses, from looking at the local parish registers he appears to have had a total of nine children, four with his first wife Mary and five with Elizabeth. A tenth child, ‘Maud Buxton’ is shown living with him and his family at 27 King Street in 1891, however this was actually Maud Ling, my great-grandmother and Samuel’s niece by his sister Mary Ann. It is notable that while her siblings all went on to embrace travelling lifestyles under the influence of their itinerant pot dealer father John Ling, Maud, under Samuel’s guardianship, remained in Alfreton and married local miner Tom England. We will return to Maud and her family at the end of this post.

* * *

Charles and Miriam’s next child after Samuel was Emma Elizabeth Buxton, who was born in Alfreton on 15 February 1863. The censuses of 1881 and 1891 show her assisting her parents at the Devonshire Arms inn (perhaps as a cook or bairmaid), but sadly she died prematurely at the age of thirty two. Her younger sister Rose Ellen was born four years later on 18 March 1867, and married a greengrocer from Coventry named William Henry Beresford. She had one daughter with the unusual Old Testament name Mahalah. Like many of her siblings Rose spent most of her life on King Street, first at the Devonshire Arms and then at number 122 in 1891, when she was recorded as a dressmaker, and at number 46 in 1911. Her last known address was the Midland Hotel in Ripley where she died on 28 August 1925.

According to her probate record, in the year Rose died her effects were valued at £295. There is a stark contrast here with her younger brother Frederick Charles Buxton (b. 11 Mar 1870), Charles and Miriam’s third son, whose estate was worth £8,337 2s. 7d. by the time he died. Like his older brother William, Frederick was a fruiterer and greengrocer but also sold fish and game from his shop at the junction of Alfreton High Street and Bonsall Lane. The photograph below from Around Alfreton shows Frederick’s shop at around the turn of the century. The figures in the foreground are almost certainly Frederick himself and his daughter Lucy Buxton (b. 8 February 1899, Alfreton, Derbyshire).

Lucy was one of two children by Frederick’s first wife Lucy Matilda Thomas, who he had married at the age of twenty one in her home parish of St. Cuthbert’s in Wells, Somerset. Lucy Matilda died in early 1899, possibly while giving birth to her daughter, but within a year Frederick had already remarried. His second wedding to Scottish-born Mary Ann Taylor took place on 31 January 1900 and they went on to have three sons together. Further details from Frederick’s life can be found in his obituary in the The Derbyshire Times, which described him as one of Alfreton’s best-known residents.

Given the respect and status Frederick seems to have enjoyed in the local community it is highly likely his nephew Charles Frederick Ling was named after him. My grandfather Frederick England was in turn probably named after one or both of these men (his great-uncle and maternal uncle respectively) and I got my middle name from him. Therefore, through the transmission of this one name it is possible to trace the legacy of an individual born in 1870 across four generations, four families, and four individuals separated by more than a century.

* * *

Charles and Miriam’s fourth son George Henry Buxton was born three years after Frederick on 14 April 1873. Like his older sister Emma, George started out assisting his parents at the Devonshire Arms before working as bricklayer’s labourer and coal hewer. In 1899 he had married a Nottinghamshire woman named Alice Morton with whom he had four children. The 1901 census records him living next to his brother Frederick’s shop on Bonsall Lane, but by 1911 he was living just off King Street at 5 Independent Hill. His probate record from 1953 shows he was still living there when he died at the age of eighty, and his effects were valued at £593 5s. 11d.

Unlike some of his siblings, George’s name does not appear much in local newspapers, and therefore we know little of his personal life beyond what was included in the census and other official records. The only significant story to mention George (reproduced below) recounts an incident at the King’s Head inn when he and his younger brother Alfred were fined for refusing to leave the premises after mocking a female singer (The Derbyshire Times, 7 June 1899, p. 3, col. 4):

Although this seems to have been George’s first and only brush with the law, this was not the case for Charles and Miriam’s youngest son Alfred. Born on 2 March 1877, at the age of fifteen he had already been fined £1 4s. 2d. for “using obscene language to the annoyance of passengers on the street” alongside two other boys. All three had received cautions before (The Derbyshire Courier, 27 December 1892, p. 3, col. 4). Shortly after his assault charge at the King’s Head in 1899 however he appears to have put such youthful misdemeanors behind him, and following his marriage to Harriet Jackson on 21 December that year there were no further stories like this in the press. The couple lived at West Street in South Normanton for a time, where the 1901 census recorded Alfred as a sawyer, before moving to 14 Amber Row in Wessington. Here Alfred worked as a labourer at the local coal mine before being promoted to colliery banksman.

Unusually for a thirty seven year old man in a reserved occupation, on 21 January 1915 Alfred enlisted for military service in the Great War and was appointed to the Royal Field Artillery. According to his service record he was posted to the No. 6 Depot at Glasgow on 23 April as part of the 31st Reserve Battery, where he would have served in a remount training unit preparing horses for the frontline. On 13 March the following year he was transferred to the 5th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers for two months before being discharged with pay on 2 May. There is a brief note in his service record where his commanding officer described his character as “Very Good, Sober, Thoroughly Trustworthy”.

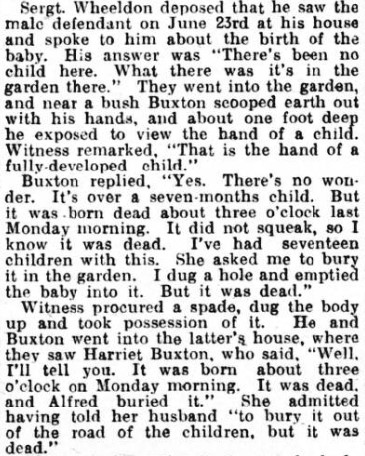

In light of these commendations the events of four years later come as an even greater shock. On 25 June 1920 Alfred and his wife Harriet were questioned by a coroner following the ‘discovery’ of a stillborn infant’s body buried in their garden (The Belper News, 2 July 1920, p. 8, col. 4). The couple were accused of concealing the birth, a crime which carried a maximum sentence of two years’ imprisonment, and a trial was held to determine their fates. A witness statement recorded in the local press gives a detailed and moving account of the incident and how the police came to learn of it (The Belper News, 6 August 1920, p. 8, col. 3):

Following a special magisterial sitting the couple were acquitted, as there was no evidence they had ever attempted to conceal the birth (The Nottingham Evening Post, 8 November 1920, p. 2, col. 1), but having a private tragedy like this play out on such a public stage for several months must have made their victory a bittersweet one at best.

The unnamed stillborn infant at the centre of this case would have been Alfred and Harriet’s seventeenth child since their marriage. By the time of their trial the family had moved back to Alfreton and were living at Outseats Terrace, and this was still Alfred’s address when he died at the age of sixty nine on 12 June 1946. His probate record from the following year gave the value of his personal effects as £619 4s. 7d. Although no photographs of Alfred have surfaced yet, the picture below shows his eldest daughter, Ada Spencer (née Buxton), with two of his grandchildren.

* * *

Having looked at Charles Buxton and Miriam Hall’s seven legitimate children, let us return now to Miriam’s first child, Mary Ann Hall. Born in Alfreton on 29 November 1851, Mary Ann’s first five years were spent living with her mother’s family in Carlton, Nottinghamshire. Following her mother’s marriage to Charles in 1856 however it appears she quietly dropped the Hall name and was thereafter known as Mary Ann Buxton. The question of her paternity was discussed at length in the previous post, and the reasons for my conclusions will not be repeated here, but it seems quite possible that Charles himself had been her biological father all along. This would certainly explain why he appears to have been so ready to bestow his family name on her, and why he is explicitly recorded as her father in both the 1861 census and in Mary Ann’s marriage certificate from 21 March 1871.

Mary Ann’s marriage to the general dealer John Ling and her children by that union were described in Travelling with the Lings (part 3), but here follows a summarised account of their years together. After their marriage they lived at 135 King Street in Alfreton for around six years, during which time Mary Ann gave birth to three children, before moving to Ripley High Street in about 1877. Here Mary Ann had two more children, including my great-grandmother Maud Ling (b. 17 April 1881), and from the 1881 census we can see that both she and her husband John had begun specialising as earthenware dealers by then.

At some point before the birth of her sixth child in 1888 the family (minus Maud) relocated to Doncaster, possibly via Brampton, where they continued to trade as glass and china dealers at number 34 Silver Street. Interestingly, in the 1893 West Riding edition of Kelly’s Directory only Mary Ann’s name is recorded, suggesting she had taken over the day-to-day running of the business. One possible explanation for this could be that her husband’s health had already begun to fail by this point, as on 13 December the following year he died of lung congestion at the family home at 12 Silver Street, just three months after the birth of their last child, Olive Emma Ling.

By 1901 Mary Ann had moved the family’s china business back to Alfreton and was living with her daughters Maud and Olive above their shop at 16 King Street. That year’s census shows them sharing their home with a thirty eight year old lodger from Poland named Louis Goodman, a travelling draper and hawker. The pictures below show their former home on King Street as it appears today.

For an idea of what Mary Ann’s shop might have looked like at the time, this photograph of Arthur Smith’s china and general goods shop at 134 King Street circa 1911 may provide some insight.

It is even possible Smith’s business was a continuation of Mary Ann’s, considering its location and the type of goods they sold. Indeed it would have made sense for her to sell her business at around this time, as on 9 November 1910 Mary Ann had married her second husband Thomas Bestwick, the recently widowed publican at Alfreton’s Railway Hotel, at the United Methodist Chapel in Somercotes. The 1911 census shows her and Thomas running the pub together at 105 King Street alongside her youngest daughter Olive and three-year-old step-son Melville Bestwick. Her age is recorded as fifty eight, however we know from her birth certificate Mary Ann was actually fifty nine at the time, a rather scandalous eleven years older than her new husband.

As this is the last census currently open to the public, Mary Ann’s movements after this date become harder to trace. We know her husband Thomas died on 1 February 1929, and that according to his probate record his last address had been ‘Holly House’ on South Moor Lane in Birmington, near Chesterfield. Presumably Mary Ann had been living with him at the time. Ten years later the sale of this house was recorded in a local newspaper:

Sadly we know from her death certificate that Mary Ann’s final days were spent at Storthes Hall Mental Hospital near Huddersfield, where she was admitted on 19 April 1938, three months before she passed away on 30 July. The cause of death was identified as lobar pneumonia, and she was said to be eighty eight years old, although she was in fact only eighty six. Perhaps the most intriguing detail on her death certificate however is the entry in the ‘Rank or Profession’ column, which reads “of Caravan, Toll Gate Hotel Yard, Old Mill, Barnsley U.D”. This was both her last known address and that of her travelling showman son, Charles Frederick Ling, her next of kin in the hospital’s admittance records. According to one researcher, Mary Ann had been travelling ever since her husband’s death in 1929 (Steve Smith, e-mail message to author, 11 September, 2016), but even before this she and Thomas had apparently been operating automatic machines at fairs throughout the Nineteen Twenties. Despite having also been a Hall, a Buxton and a Bestwick in her time, perhaps Mary Ann had always felt most at home travelling with the Lings?

Postscript

The influence of the Hall and Buxton families on the Lings and Englands can be seen in their shared network of personal and business connections, as well as the names they passed on to their children, but perhaps most of all in the long shadow cast by a persistent rumour concerning Mary Ann’s missing fortune. Growing up my mother remembers her father Frederick England claiming there was “money in probate” on numerous occasions, and a series of letters from the Belper Register Office seems show how this elusive wealth was connected in his family’s mind with Mary Ann. Two of these from September 1949 refer to searches for her death certificate, as well as those of her parents Charles and Miriam, which they presumably needed in order to find the corresponding entries in the National Probate Index. It is not clear how far they got but the value of Mary Ann’s effects at the time of her death was just £280 12s. 2d. Even when one adds the £123 left by her father and her mother’s £985 17s. 1d. the sum total hardly justifies the legendary status it acquired. It is possible the rumour’s origins lay with Mary Ann’s second husband Thomas Bestwick, who left behind a personal fortune worth £3,833 3s. (approximately £128,100 in today’s money), but then again it could also just have been wishful thinking on my family’s part. The search continues.

Sources:

Baker, Chris. “Royal Artillery depots, training and home defence units”. The Long, Long Trail. Accessed 17 July, 2016. http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/regiments-and-corps/the-royal-artillery-in-the-first-world-war/royal-artillery-depots-training-and-home-defence-units/.

Alfreton and District Heritage Trust. Around Alfreton. Bath: Chalford, 1994.

Kruse, John. The Victorian Bailiff: Conflict and Change. [s.l.]: Bailiff Studies Centre, 2012.